State of tenant evictions in RI: Bleak, with scattered glimmers of hope

"It's often thought that poverty causes eviction, but it's more often the case that eviction causes poverty..."

The Rhode Island Center for Justice gave a fascinating and informative presentation on the state of evictions in Rhode Island to the Providence City Council Housing Crisis Task Force last Thursday. The task force is chaired by City Councilmember Mary Kay Harris (Ward 11). The presentation was given by Jennifer Wood, Executive Director of the Rhode Island Center for Justice; Sam Cramer, legal fellow at the Rhode Island Center for Justice; and John Karwashan, Supervising Attorney at the Rhode Island Center for Justice.

The Rhode Island Center for Justice is a small nonprofit law firm that represents individuals who cannot otherwise afford a lawyer, and one of their largest areas of focus is on eviction defense and housing. The majority of their cases are on behalf of Providence residents.

The following transcript has been edited for clarity.

Jennifer Wood: We work with many Providence residents in the context of the district court and eviction, and we have some statistical material to present. We were asked some questions about what are we seeing in terms of trends, such as how many evictions, how the eviction rate in Providence compares to the recent past, et cetera. We value the opportunity to answer your questions about the actual lived experience of those who are facing eviction in court.

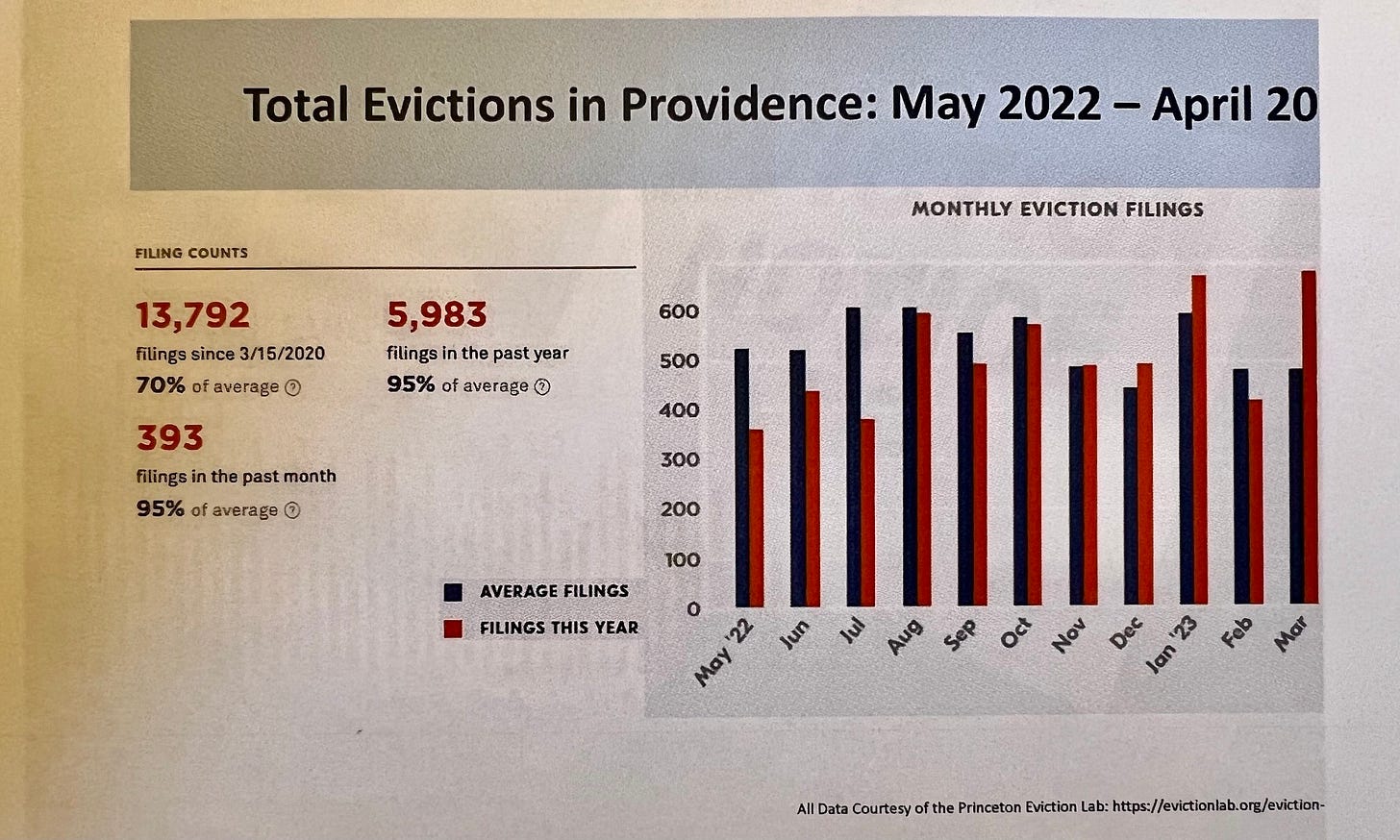

Sam Cramer: This slide is the total number of evictions in Providence over the last year. I put together this presentation in May or June, which is why the numbers go from May 2022 to April 2023, as noted at the bottom. These numbers come from the Eviction Lab at Princeton, which tracks filings across the country and in most states, Rhode Island being one of them.

One of the things that you'll see first is that there were 13,792 filings since March 15, 2020. That's an important date, right? That's the beginning of the recognition of the pandemic in a lot of public policy. That number is 70% of the average and that represents a marked decline over the course of the pandemic.

However, the next number, the actual evictions that have occurred in the last year, from May 2022 to April 20, 2023, is 5,983. That's 95% of the average. Eviction filings dipped during the pandemic. In the last year, we've seen a rise in filings such that we're right back to where we were, as things like the CDC eviction moratorium and Rent Relief Rhode Island have ended.

Sam Cramer: On the topic of Rent Relief Rhode Island, there's an interesting trend that you can notice in this chart. In June 2022, evictions were still below average. The column on the right is the actual evictions, and on the left, the darker column, that's the average over time. Things remained below average in June and July.

It's important to note that Rent Relief stopped accepting applications on June 1st, 2022. Mark that down as the date when relief applications stopped coming in and what you see is a steady uptick in filings, against average, as fewer and fewer people were receiving assistance. The Rent Relief Reliant program was paying some tenants between the months of June and November, but you can see that very quickly, in August 2022, filings jumped right back up to average and remain at or above typical filing numbers, for the most part, from August until April. The takeaway is that the program had a big impact on reducing filings. Making rental assistance available decreased the number of filings.

Jennifer Wood: Individuals who had an arrearage were eligible for the program. Because it was emergency rental assistance during the era of the pandemic, people may have lost employment or lost a member of the household resulting in a reduction in employment. People fell behind. Rent Relief was designed to address that.

I think the point my colleague is making is that there is a well-established gap between earnings and rent. The pandemic exacerbated this trend and a lot of people slipped further behind, but Rent Relief was not a forward-facing rental subsidy program. That's a whole different thing that we should talk about tonight. Rent Relief was initially an emergency program to address people who had fallen behind on their rent due to, or during, the pandemic.

Rent Relief had a major protective effect, reducing the number of evictions because, even pre-pandemic, as has been well documented by Housing Works RI and other sources, that there is a serious gap between average earnings and average rent. That is a discussion that many of you, I'm sure, have heard in this committee about people who are rent burdened or severely rent-burdened, that is, paying way more, as a proportion of their income, than they can afford to on a monthly basis.

Sam Cramer: Rents have inflated over the last year. Rents have been inflating higher than the rate of inflation or other consumer debts for years now. And that's not a trend that we see slowing down this last year. Rents keep going up and are going up faster, than other things that people are spending money on.

Councilmember Justin Roias (Ward 4): I have my theories as to why rents keep rising and rising, but I’d like to hear why you both think that rents are rising.

Sam Cramer: It's an incredibly complicated question. I don't know that I have a clear answer for it, but there are a lot of factors in play. There's been a consolidation of ownership of rental properties, and anytime you see a consolidation of ownership, you see greater control over large segments of the market, which then allows for prices to go up. There's a lack of housing supply in Rhode Island right now, for both affordable units and otherwise.

I've looked at vacancy rates in the state of Rhode Island. I've seen numbers floated anywhere from two to four or five percent. The Economic Progress Institute said that any vacancy rate below six percent is going to create upward pressure on prices That is a lot of it, but then there are a lot of other factors in place too.

John Karwashan: One of the other major factors is the unaffordability of most housing in Rhode Island. Prices on the East Side are super high. Prices in the West End are super high. Prices in Mount Pleasant are similarly rising. The South Side is one of the only areas in Providence where you can find affordable housing. And a lot of that supply is being purchased, renovated, and rented out at higher prices.

Jennifer Wood: I would point to the increase in property values that John was mentioning. We've seen that trend nationally, and locally, during the pandemic, rising prices made it more attractive to purchase these properties. But when you pay higher prices to purchase property, you have to turn around and pass those costs along to renters.

This is not a scientific study. For that you need that go to the Housing Works RI data. But anecdotally, when we interviewed our clients before the pandemic, we would hear, "I've been paying $850 a month for my apartment, which may or may not include utilities." These were low-income individuals who were coming to us for help.

In the intervening three years, I can't remember the last time someone came into the office and said their monthly rent is $850 or $950 a month. Now it's $1500, $1600, $1700. And these are families that couldn't afford $900. It's stark and dramatic. We're also seeing a pattern of people doubling up because of those price differences. Our clients were struggling at $950. At $1550 or $1600, it's literally unaffordable.

Sam Cramer: And that creates some other pressures in terms of the effect that it has on people when they're living in a place that has historically been affordable or is cheap because it might be substandard housing. There's a market for substandard housing and a lot of people who are of limited means end up in that market for any number of reasons. If their option is to either put up with that or move, and moving means almost doubling the rent, a lot of people feel stuck.

I want to bring up the elephant in the room. We're talking about why rents are going up, but one of the big reasons is that there's nothing to control it. We're talking about market forces here, right? We're talking about free market economics and how that plays into people's ability to purchase housing. There isn't an external control on that.

John Karwashan: When rent that was $900 pre-pandemic rises 50%, it's now $1350 a month, which is a pretty ordinary rate to pay here in Providence. But people's incomes did not increase in the same way. While rent increased by potentially 30, 40, or 50%, incomes diminished, because people lost their job, or lost a partner who lost a job, and there's no ability to keep up with those rents.

Jennifer Wood: You are policymakers and elected officials. I testified on several pieces of legislation this year relating to the fact that there is no limitation on the frequency or amount of rent increases in the State of Rhode Island or in the City of Providence. There is no ordinance or statute that provides any stabilizing pressure on rent. When I was testifying on these bills, there were a number of different policy proposals to either limit rent increases to one time per year, limit increases to inflation, or to an increase of 10%, or whatever it might be.

There are many solutions from which one could choose, but right now, there is literally no limitation on the frequency or amount of rent increases. That means, in a theoretical universe, rent could be raised once a quarter or twice a year, and by any increment. That's very challenging. If you are on a month-to-month tenancy, you don't have that rate locked in for a year. Without adequate notice required by law, you don't know whether or not rent might increase a couple of times in a year.

Mary Kay Harris: You mentioned the consolidation of owners. Can you elaborate on that?

Sam Cramer: There's been a trend over the last several decades, but especially since the pandemic started, where a lot of rental properties have gone on the market. These properties have been purchased by large-scale capital interest hedge funds, investment funds, and that kind of thing. When a number of properties are being bought up by the same entity, that entity has disproportionate control over pricing. Some owners might almost have a monopoly on rental units. I can't speak specifically as to how many properties are owned by which particular entities in which particular neighborhoods, but I think that's definitely worth looking into.

This situation is a partly a product of a free market system. Without regulations and protections against things like monopolies, and without controls, you see upward pressures on rental costs.

Justin Roias: Real estate, in my view, is the wild, wild West. As long as housing is associated with profit, folks are going to continue to get squeezed. I hope my colleagues will have an appetite for some policies that could stabilize rents across the city.

Yesterday I was at a neighbor's house and I looked into who owned this property that iss not being taken care of. And I just keep seeing LLCs, LLCs, LLCs. When I look into this sort of thing, I would love to see a normal person's name instead of an LLC. It's difficult to know if mom-and-pop landlords are actually a thing in the city anymore because folks hide behind LLCs. It's a huge problem.

Jennifer Wood: I'm really pleased that you brought up the issue of a rental registry because there's a little bit of progress to report. There was legislation passed [H6239/S0315], at the request of the Attorney General that will create, at the Department of Health, a transparent, public registry of properties. The focus of that registry is on lead enforcement and whether or not the properties have properly maintained their lead certificate, but it also includes features like requiring a name, address, and contact for the owner of the property. As the attorneys representing tenants, we often have to do a lot of sleuthing to figure out exactly who owns what properties because the name that is on the eviction that is filed in court may not be the real party of interest.

It may be that it's an LLC, but we're trying to get to the bottom of who's in charge, and who's been collecting the rent. Is it the person who collected the rent, an authorized agent of the owner, or not? That legislation was a step forward and we were very excited to see it pass. It's going to be a year and a half before the legislation really takes root and is up and being administered, but it will be a step forward in terms of transparency.

Councilmember Pedro Espinal (Ward 10): We spoke earlier about the $900 average apartment rent that we had about five years ago. At that time one could purchase an average home, let's say in Providence, for around $200k. At that price, one could afford to rent an apartment out for $900, but if you read the paper this morning, a single-family home ended up costing over $500k. There's just no way an owner is going to be able to rent an apartment for $900.

So valuation is playing a major role here, combined with house insurance. Speaking of Providence, our population is larger, we have 200,000 people, and we have a lot of competitors coming from out of state that are willing to pay for houses to rent to people. That's a major factor.

Jennifer Wood: Thank you, councilman. The gap between income and affordability, and all the pressures you're pointing to, are the same pressures that we're seeing. It would be my assertion that there are really two macro-level policy solutions. You either have to affect the income or you have to affect the rent. This is the mismatch and it's a well-documented mismatch that has developed over the years.

I'm going to use an analogy. We, as a nation, made a decision about 10 years ago to have a systematic approach to the subsidized purchase of healthcare. It was a huge undertaking with much controversy, but policymakers determined that there would always be a gap preventing some of the lowest-income residents from being able to purchase health insurance and access healthcare.

As a nation and as a state, we looked at how we might fill tate gap if the income is too low and determined there's going to be a population that will need a healthcare subsidy. There's a role here for subsidized housing, and with all of the market forces that have been described, we cannot make our way out of this disconnect, in my view, until we have subsidized housing.

We have two paths. We can either subsidize income and have guaranteed income levels that will make housing affordable at the market price, or we subsidize housing in greater proportion than we have in the past. You, as policymakers, know that there are very long waiting lists for Section 8 housing and access to publicly subsidized housing.

When you have a gap between the cost of a commodity and what people earn, there are actions that government can take. We, as a nation, decided to subsidize access to health insurance. There, we built on the successful program of Medicaid. We have a successful program of public housing and we have subsidies like Section 8 that allows low0income tenants to go into the private market.

As someone who was very involved, in a former life, with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act in Rhode Island, to me the parallel is obvious. You have a disconnect between income and the cost of something that is a fundamental human right. I would assert that healthcare and housing are both in that category.

Some members of our community will require a subsidy in order to access affordable, safe housing. And I want to emphasize safe because public housing and subsidized housing have more oversight of health and safety factors. Public Housing Authorities have some transparency and accountability around health and safety, and Section 8 comes with certain requirements for inspection and upkeep.

Our clients often find themselves with much less accountability for their rental homes because code enforcement is so overtaxed. Code enforcement does their best, but keeping up with the number of properties in Providence that require immediate attention is a huge undertaking. Until we have programs that guarantee income that makes the purchase of safe, healthy housing affordable, or subsidize the housing, there's going to be a gap.

We don't know how much of the population is in that gap. We've got over 95% of all Rhode Islanders with access to affordable health insurance. That didn't happen because magic happened. It happened because we have a carefully constructed program of subsidies, with Medicaid expansion and the creation of a health insurance exchange where people can purchase health care below market price with a subsidy. I think the parallel is very clear between health and housing, and we know that those two things are seriously intersected because a loss of housing also triggers a loss of health.

John Karwashan: At the risk of stating the obvious, as that gap increases between what people are earning and property values, there's only one group of people who can afford to purchase the properties. That's the corporate entities that we've talked about over the past 10 or 15 minutes. There's one small portion of the population, who controls a lot of the money, and they're able to come in and buy, whatever the property value is. If it's $500k, $700k, or $900k, it doesn't matter to them. They'll buy it, and they have no regard for what happens to the community when that happens.

And for what it's worth, I think the dream of having a mom-and-pop owners come in and buy a three-family to live in and rent, is an unattainable dream for most folks working an average job. I don't think folks can realistically afford these houses - the down payments, the mortgage, the insurance, and the 7% -8% interest rates that they're charging. It's crazy.

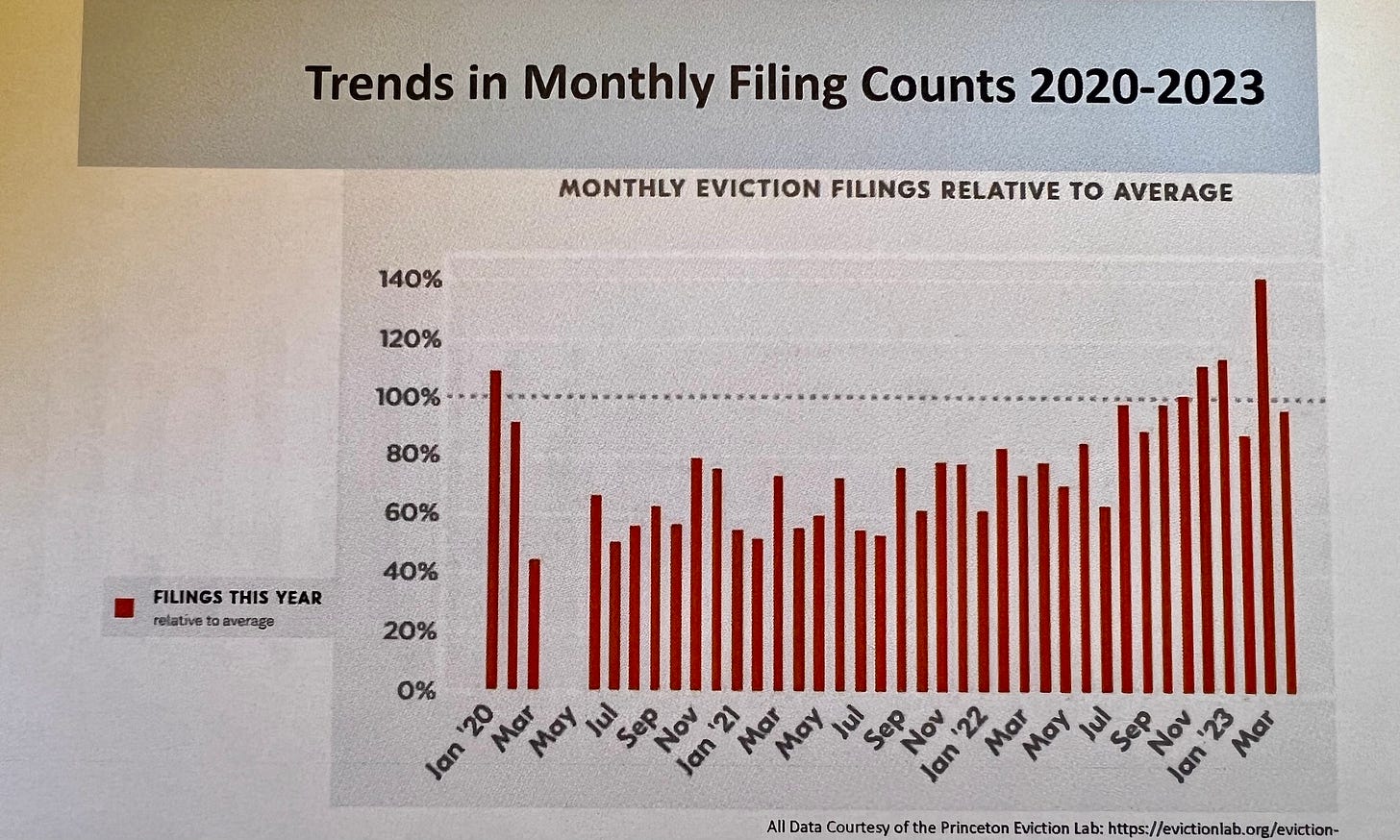

Sam Cramer: The next slide is monthly eviction filings from 2020 to 2023. This provides a slightly broader picture. What you're looking at is blue versus orange. Blue is average evictions over time and orange is what was actually happening during those months. During the pandemic, when there were protections in place, like the CDC moratoria and access to rental assistance, filings are much lower.

Towards the end of the graph, where it says July, September, November, or January 2023, you can see that eviction filings go back up to historic levels and in many months actually higher than historic levels. That coincides with the first slide where I pointed out that Rent Relief ended in June of 2022 and paid out for a couple of months thereafter. That's exactly when we see the filings go up.

Sam Cramer: When there's a will and the ability to implement certain controls on the market and on people's behavior, we see filings go down and people are stabilized in their homes.

The next slide is similar. That dotted line is the average number of filings per month and you can see which months were below and above that line. From January 2020 - which was before protections were in place, right when the pandemic started - through July 2022, we had below-average evictions. Then, afterward, we shot back up to historic norms, or above.

Pedro Espinal: I have a question. The courts closed for a period of time. Where is that?

Jennifer Wood: See the gap there in May 2020? When people became fully aware of the pandemic, around March 2020, there was a period when the courts closed for all purposes - just closed. But actually, contrary to popular perception, most courts began to gradually reopen, even during 2020, doing either remote hearings or a limited calendar, or having different kinds of social distancing and masking to protect people coming into the courthouse.

This graph shows filings, not hearings. There was a period when no cases were being filed, but that was very brief and then cases were being filed, but perhaps not heard. There were significant delays in court cases during this period. There was also the partial CDC moratorium which affected filings. There were a whole bunch of policy solutions swirling around in that period. Can you see the red line below the dotted line? Those are below-average filings, but eviction filings didn't go away entirely except during that one period between March and July. There's no red line because the courts were actually closed and then very slowly and gradually reopened.

Sam Cramer: An important point, since we're on the topic of those protections, is that all these protections were designed to forestall evictions for nonpayment of rent, under the theory that the pandemic was disrupting people's ability to earn money and that disruption in their income would then lead to an inability to pay the rent, so we needed to slow things down.

But all throughout the pandemic, there was nothing that protected month-to-month tenants from the normal eviction process where it wasn't about the rent, but about a landlord exercising their right to ask somebody to vacate a unit with at least 30-days notice, as is the law. A lot of the evictions filed during that time were of that type: termination of tenancy cases. Those often happened after the sale of the home or when the owner wanted to put the house to a different use.

One of the ways the tenants can be protected from that type of disruption is by having a lease. Most tenants I work with don't have a lease for a term. Obviously, they don't have a right to stay past that lease, but during that lease, as long as they're abiding by the terms of the lease and fulfilling their obligations to pay rent and behave as a reasonable tenant would, they're protected from their tenancy being terminated before the term of that lease ends, which provides a certain measure of stability and credibility.

A lot of people initially have a lease when they move into a place, then that lease expires and they continue as month-to-month tenants. I think we're all probably aware of that process. Many of us have lived that experience, myself included. You sign a lease and then 10 years later you're like, wait a minute, do I have an agreement? Do I have a lease?

Mary Kay Harris: I have a question about leases. I've heard landlords say that they are no longer renting for term leases, but month-to-month. Are you experiencing that in your work?

Sam Cramer: I'm aware of landlords who prefer to have month-to-month leases with tenants, I'm aware of landlords who don't want to have leases at all, and I'm aware of landlords who are perfectly happy to sign leases for a term.

Jennifer Wood: The minority of clients who come to us have a lease and that's not new. Since I came to the Center in 2017, one of the first things we asked was, "Do you have a lease or are you on a month-to-month tenancy?" And the vast majority of our clients who are low-income tenants did not have a written lease. And that leads to all sorts of complications.

Justin Roias: If the majority of your clients don't have a lease and are month-to-month, that makes them vulnerable in my view. I'm a renter and, full transparency, I'm on a month-to-month lease and that scares me. I think a lot of residents in the city are on a month-to-month lease and I would like to get real data to find out what that number is because it could inform some of what we do here.

Kristina Brown [Providence City Council Director of Policy and Research]: On that note, are you aware of any local or state legislation to mandate leases or any laws that exist now?

Jennifer Wood: As we are unpacking this question, it strikes me that I haven't seen legislative proposals to require a term lease. There are pros and cons for both parties. There are reasons why a tenant might not want to be locked in for a year, just as sometimes a property owner may not wish to be locked in for a year. But generally speaking, if you know you're going to be in the place for a while, a lease provides a protective feature against increases during the term. That's the most obvious benefit - you're not at the whim of rental increases.

I haven't seen legislative proposals to limit month-to-month leases, which for our client base is the dominant form of tenancy. I'm not sure that was the case when I first started renting. 40 years ago it was very typical to have a lease. I think that may have eroded over the last four decades such that whatever the forces are on both sides of the tenant/landlord equation, leases have become much less common in low-income rentals. I think that if someone is renting a luxury apartment, they probably have a 12-month lease, and that speaks volumes about whether or not people think leases are advisable.

Sam Cramer: In my experience representing tenants over the last three years, a great number of my clients had a lease at one point and that lease expired. Many of them, the great many of them, would like to get back on a lease and they may have asked to do so and were not offered a lease. There is nothing to compel a landlord to offer somebody a lease right now. Many of the clients I've represented would have accepted the offer of a lease had one been made. But that wasn't on the table during the course of their relationship with their landlord.

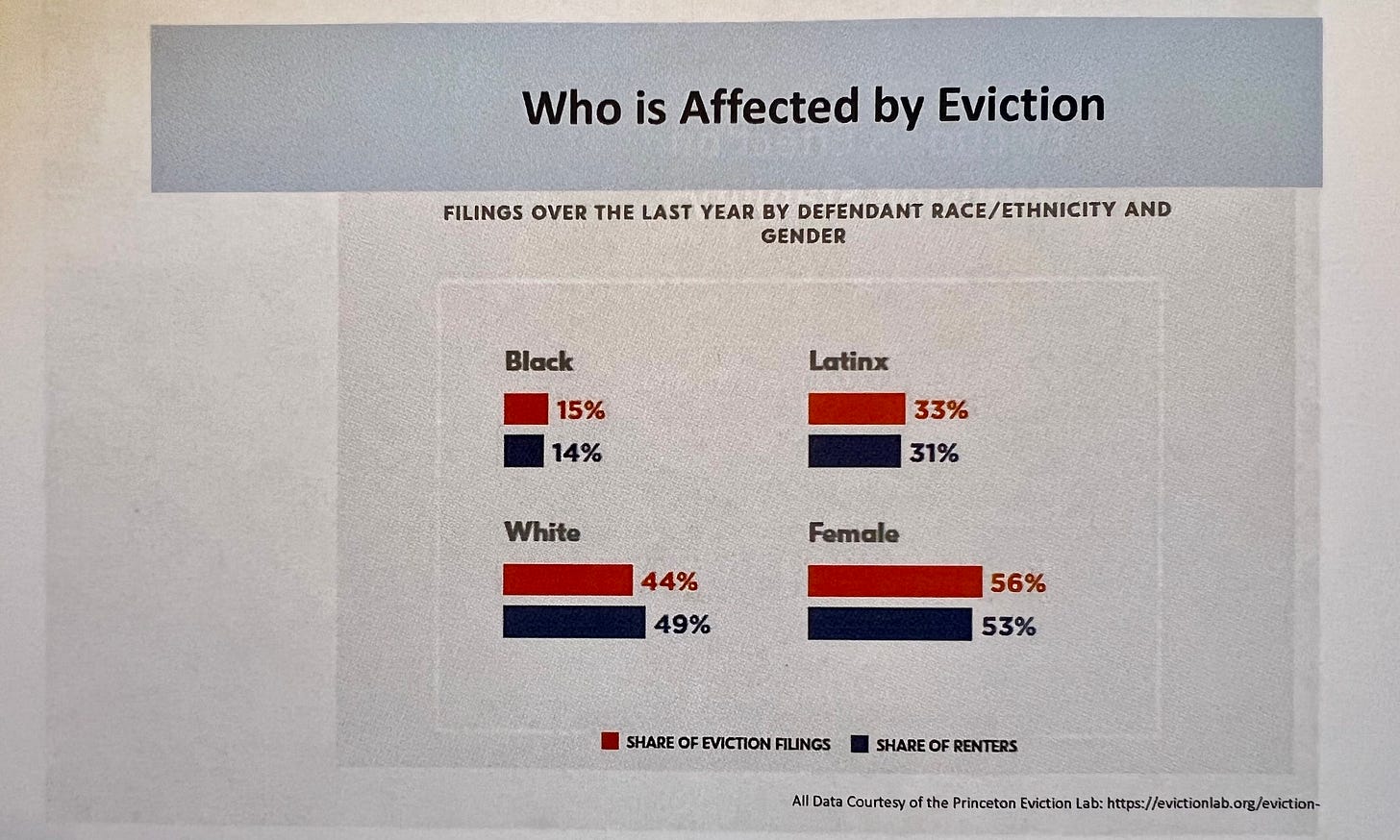

I figured it would be valuable to look at the data on who's being affected by evictions. The orange bar is the share of the population that has an eviction filed against them. The blue bar underneath is the share of renters in the population. Black individuals comprise 14% of renters, but 15% of evictions Latinx individuals comprise 31% of renters and 33% of evictions; white individuals comprise 49% of renters and 44% of evictions. So we see some disparities along the lines of race. We also see disparities along the lines of gender. People identifying as female are being evicted at a rate of 56%, as opposed to 53% of the population.

John Karwashan: I ran some numbers specific to Providence today. It's important to remember that this is just Center for Justice numbers and doesn't include Rhode Island Legal Services or any tenants who may have had the ability to hire private counsel, which is a very small amount. From January 1, 2023 to the present, we have helped a total of 377 folks. 29% of those folks identify as Black, 31% identify as Hispanic, 4% identify as multiracial, 2% identify as Native American, 24% identify as white, 7% identify as other, and a small percentage identify as Asian and Pacific Islander.

We spent some time a little while ago talking about income levels. The average individual who comes through the Center for Justice with an eviction, since January 1st, 2023, has been at 106.18% of the poverty guidelines, pretty is right at what is listed as poverty in the guidelines. These numbers include subsidized housing, private housing, and public housing in the City of Providence. These numbers are only for the Center for Justice and only for the City of Providence. When you add in Rhode Island Legal Services numbers, we realize the number of folks who have experienced an eviction, just in 2023, is much greater than the 377.

Jennifer Wood: There's a big gap between what we saw in our caseload and this statewide number from the eviction lab. I think the number skews more heavily towards harmfully impacting families of color in the city.

We always collect racial information so that we could understand who is being most impacted. But in the court system, there's no reporting of that data. We knew that there were 8,000 evictions on average in the court system in Rhode Island before the pandemic, but we had no data on how that broke down. We and our colleagues at Rhode Island Legal Services have been collecting that information, in part through a project that the city had been supporting for eviction defense. We now have two or three years od data and are able to draw some meaningful conclusions about the disparate impact of eviction on residents of color in the city.

Kristina Brown: How many households with children? Do you have any data?

John Karwashan: It's not totaled up. But I would say at a quick glance, it's probably upwards of 60% to 70% of these households.

Jennifer Wood: In a report we filed at the end of last month,in excess of 50% of all households impacted by eviction included children under the age of 18, and in many instances, more than one child. We'd be happy to share that data with the committee.

Councilmember Miguel Sanchez (Ward 6): In terms of workload and cases, are you and Rhode Island Legal Services pretty similar, or is one doing more cases a year than the other?

Jennifer Wood: Rhode Island Legal Services has two or three more attorneys than we do. That's a slightly bigger caseload, but the average number of cases handled is very similar. We've both been actively looking at the issue of access to legal defense for eviction for about five years. We're part of a national network looking at the issue of eviction and the right to counsel.

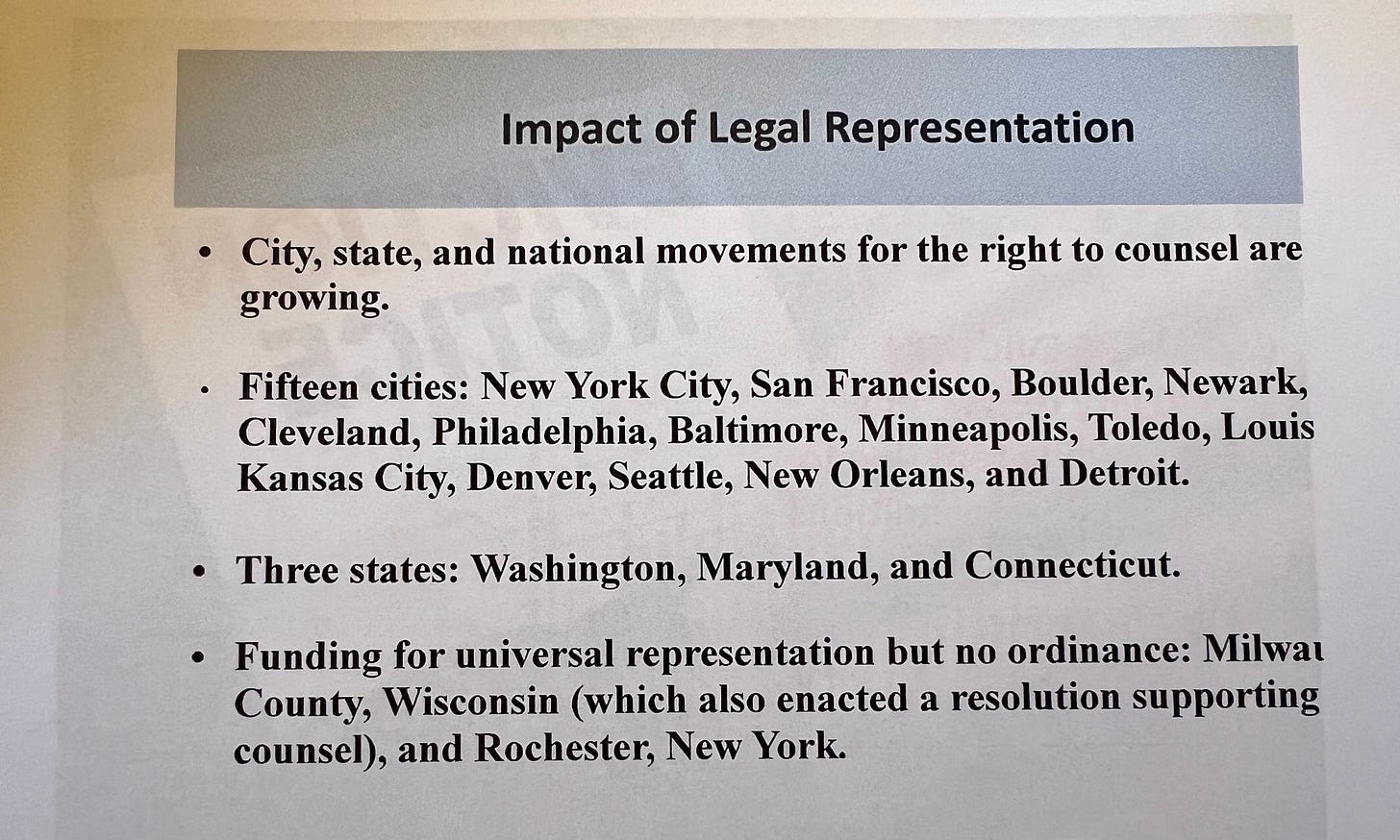

This national movement is thinking about whether or not housing is such an important human need that it rises to the level of a right and whether or not, therefore, there should be publicly subsidized access to attorneys to defend residents in the case of eviction. The most prominent case study is New York City. New York City implemented the right to counsel for eviction about seven or eight years ago and has made a significant investment in providing indigent defense - providing lawyers for tenants who are facing homelessness and are unable to afford a lawyer.

And that has been spreading nationally. There are probably about 17 jurisdictions across the country now providing a right to counsel or are moving towards it. For example, our neighbors in Connecticut have implemented a statewide right to counsel. But if you turned to us and said, "We want you to represent every low-income individual who is facing an eviction," we would say we can't, even if you were willing to pay us, because that would require significant staffing increases. We simply don't have the capacity. Even we and Rhode Island Legal Services combined don't have that capacity at this time. But it is something that we are very serious about and dedicated to trying to expand.

In Connecticut, they're phasing in the right to council by zip code. They're looking at prioritizing zip codes that are known to have a high proportion of residents below a certain income level. I go to regional conferences with legal aid and legal services directors and I definitely do not recommend the zip code approach because it's driving them crazy in Connecticut. It puts them in the awful circumstances of having someone call them and say, "I'm facing eviction, I have three young children, I have experienced a loss of income, I've lost my job, I've been in a car accident," and then you have to ask, "What zip code do you live in?" When they say the wrong number, they lost the lottery.

It's very problematic to implement and I think that lawmakers in Connecticut are realizing that. The program, by design, will become universal, but they have to figure out how to ramp it up. In New York City, the approach was to start with the lowest income and then move toward broader eligibility over time, because you can't just turn a program like that on and have it be at scale in the first months.

Miguel Sanchez: Is it municipalities or state governments taking a shot at this?

Jennifer Wood: Mostly municipal, but because of our size we're very quirky. If we did a statewide program, we would be smaller than the New York City program by a factor of, I don't know, 50 or 100. It's mostly larger cities that are taking this on as an issue, but there are several statewide initiatives, including Connecticut.

Miguel Sanchez: In those states, is it organizations like yours or can they tie it to the public defender's office?

Jennifer Wood: I looked at this question. All across the country and in every place where the right to counsel or expanded access to eviction defense is being implemented, it's being done through the expansion of civil legal aid and civil legal services because the capacity of the public defender is already overtaxed. For example, there's a study that demonstrates that the Rhode Island Public Defender's office is significantly understaffed and underfunded. In no other jurisdiction are public defender offices being asked to take on a new body of work when they're already not sufficiently staffed and funded for the work that they've been constitutionally assigned to do.

The way it's done in New York City is standard, which is to legislatively create a phase-in plan for implementing the program and dedicating public funds to an RFP type of procurement process where legal service providers can step up and say, "We think we can represent 20% of those who may face eviction this year." In all the other jurisdictions it's done by an array of legal aid and legal services providers, each of whom step in and commit to taking a portion of the work.

Sam Cramer: In the next slide, we talk about the causes of eviction, many of which we've already covered.

Sam Cramer: There are various reasons people are unable to pay rent, one of which is the rising costs, which we've talked about at length. One reason we've touched on very briefly, but I haven't talked about at length, is withholding rent due to substandard conditions. There are a number of people that we run into in our practice who have taken it upon themselves to say, "I'm not going to pay rent for this house because this house is not worth it." That is disallowed under Rhode Island law. You have an obligation to pay the rent or the landlord can take you to court for failure to pay the rent and evict you.

We often see things come to a head when people make that decision. They're not without legal recourse for the conditions of their apartment, however, it is a very quick way to get yourself in court for a non-payment eviction. Foreclosure is another issue, though thankfully, several years ago, following the crash in 2008, the state passed some protections for people who were living in properties that had been foreclosed on. If the person that they were renting from was the owner who was facing foreclosure, and the tenant could establish that they had a prior rental agreement with that individual, they were protected. We still see foreclosures lead to evictions, though at a lower rate and it's a much slower process.

Another issue is the sale of the property. When a purchase and sale agreement is in place between an owner and a buyer, and the buyer wants to buy the property free and clear, then people who are month-to-month tenants will receive a termination of tenancy based, in part, on the sale of that property.

We also spoke about a termination notice sent because the owner decided to do something else with the property. Owners only have to give 30-day notice to a month-to-month tenant. There are a number of reasons that landlords do this, many permissible, some impermissible. There are a number of landlords who decide they want to raise the rent, move in a family member, or want to turn the ground floor unit into a playroom for their dogs.

John Karwashan: On that last bullet, it's important to note that in order to terminate a tenancy, you don't need a reason in Rhode Island. When you terminate somebody's tenancy in Rhode Island you have to give them the proper amount of notice and that's it. It doesn't matter what the reason is as long as it's not retaliatory. There are all these causes of eviction, but at the end of the day, there's no one particular type of eviction that represents a decent portion of the evictions that are being filed, and no reason is required unless it's a certain type of housing. The majority of rentals don't require a reason.

Pedro Espinal: How is that interpreted in court though? Will a judge give an additional week or two, understanding that a person is not going to be able to find an apartment right away and they're going to be put out on the street, or is the judge less flexible?

Sam Cramer: Every case is different. The decisions that a judge makes are guided by the facts and the law. It's impossible to say exactly what a judge is going to do on any given day. Judges are bound to follow the law, they're bound to follow the statutes. The statute says that a landlord has a right to reclaim possession of a property if they deliver a legally valid notice and the notice was delivered and delivered on time. Essentially, if the landlord does everything to exercise their right to reclaim the property, then a judge is bound by the statute to order that the landlord be allowed to retake that property. There are things that tenants can do legally to forestall that, but the judge has to follow the law.

Jennifer Wood: Essentially the judge would have no legal basis unless there's some other issue involved.

Sam Cramer: The next slide is the effect of evictions on housing stability. There's a phrase that isn't on this page that I want you all to take away: It's often thought that poverty causes eviction, but it's more often the case that eviction causes poverty.

Sam Cramer: The eviction process is incredibly disruptive and that disruption cascades through somebody's life. Their ability to get to work, their ability to maintain benefits, maintain a mailing address, and to get their children to school are all affected. People's lives are upended by eviction and that disruption in their lives often has negative economic consequences. When that happens, they're more susceptible to subsequent evictions. And as that cycle progresses, the eviction process might become the catalyst for somebody to slip into a permanent cycle of poverty.

On a more granular level, eviction creates stigma. We have a public web portal in Rhode Island that captures all civil filings. Landlords use it to see if somebody's been evicted. If you're applying to rent an apartment, a landlord will go ask, "Have you been evicted before? Have you been evicted for non-payment of rent? Did you leave owing the landlord $20,000? Was there an eviction filing that was dismissed?"

Different landlords will treat that differently, but this information will follow you around and it has an impact on your ability to find housing in the future. That loss of credibility in the rental market will drive people into substandard housing, a market where people aren't making those checks, where the rents are lower, and conditions are poor.

The last two slides we can take in tandem. We talked about the right to counsel and the impact of legal representation during the eviction process. The first slide lists some of the cities and states where the right to counsel has been explored and how that was funded.

Sam Cramer: The next slide looks at outcomes when a tenant has an attorney representing them versus not having an attorney during the eviction process. You will see dramatic differences. Many more cases are settled, as opposed to going to trial in front of a judge, when there's an attorney representing the tenant. That's because the attorney is able to navigate the process, understand the tenant's rights, press the tenant's defenses if they're available, and find a reasonable compromise to the extent that the defenses provide some leverage to negotiate a settlement. When that happens, the tenant is going to get a better outcome than they would if they were proceeding alone. That difference usually means more time in the house, abatements of rent, et cetera.

Jennifer Wood: There's a lot of statistical evidence for the proposition that a tenant with an attorney will do better than a tenant without an attorney. It almost feels laughable to tell you that because if any one of you was served with a legal process and the other party was represented by a lawyer, you would not want to go alone to court. It's just obvious. You would prefer to have a professional person representing you who knows what your rights are. In places where there is not a policy decision made to ensure the right to counsel, above 90% of tenants are going alone. And before we started doing this work in Rhode Island, Rhode Island Legal Services only had enough capacity to represent people in public housing settings.

In the entire private rental market, there was no systematic defense for tenants in the state of Rhode Island until 2017. More than 95% of tenants were unrepresented, and that has a huge impact. By the way, more than 95% of landlords are represented by counsel because it's their business. They own the property, they want to have someone who knows what they're doing in the court system. There are some landlords who do it on their own, but it's less than 5%. That gap between less than 5% of tenants having lawyers and more than 95% of landlords having lawyers has an obvious outcome. Closing that gap is what we are working to do with our colleagues at Rhode Island Legal Services to do right now.

Sam Cramer: The last slide is a list of policy recommendations. We've already discussed a lot of these policy recommendations in the course of our conversation, which is heartening. You'll see that they're a mix of subsidy-related policies and ideas, and market-driven policy ideas, a combination of supplementing people's income and implementing controls on the market itself, creating conditions for the market pressures to alleviate.

Again and again we hear how serious the housing problem is in Providence and its surrounding areas. This is excellent reporting, Steve, on important information. So much needs to be done. The horrors of homelessness cannot be overstated.