Providence landlords filed 18% more evictions than in an average pre-pandemic October

"...the national trend is true of Providence, in that households with children are much more likely to be evicted or to face eviction than households that don't have children."

Boston is about six times larger than Providence, but Providence is keeping pace with the larger city’s eviction filing numbers. Over the last 12 months Boston has had around 6000 evictions filed in Massachusetts courts. Providence, 1/6th the size, has had 5,700 evictions filed. I was speaking with Grace Hartley, a research specialist with Princeton’s Eviction Lab, which tracks evictions nationwide when she dropped this bombshell on me.

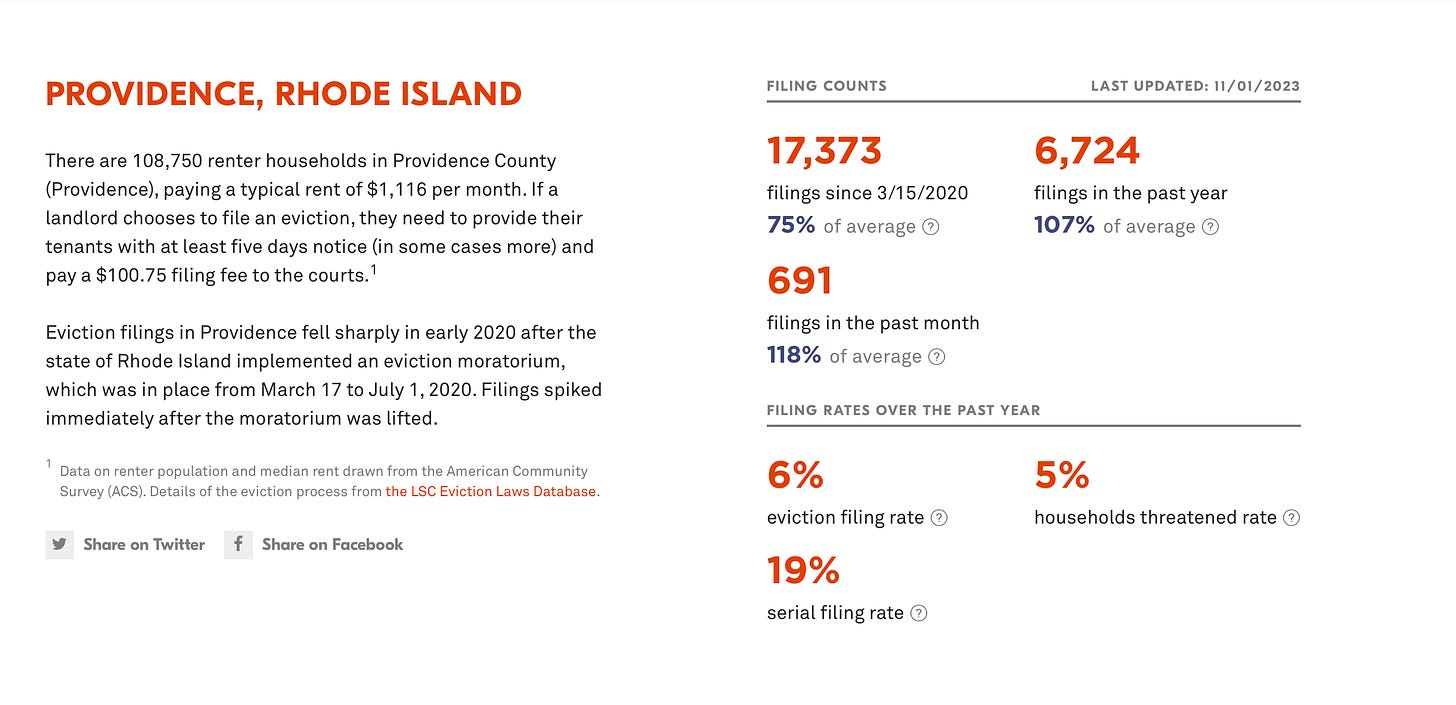

I had reached out because of an Eviction Lab report showing that this October, traditionally a month of high eviction filing activity, landlords filed 18% more evictions than in an average pre-pandemic October.

Steve Ahlquist: Right now we are seeing a surge in evictions nationwide and in Providence, we saw an 18% increase this October. What do you attribute that to?

Grace Hartley: We saw in the past couple of years, since the start of the pandemic really, that there were several rental assistance programs in place, notably the eviction moratorium and other kinds of cash assistance. Since those programs ended, we've seen that without that kind of safety net, people are struggling once again to make their rent.

There's also inflation. People are having to spend a lot more money on a lot of different things, like groceries. We've also seen that rent has gone up. Incomes have not necessarily increased, but the amount that people need to pay for rent has. The site Apartment Lists, notes that nationwide, median rents are $250 higher than they were pre-pandemic. In Providence specifically, rents have increased 25.7% since before the pandemic.

In Providence specifically, rents have increased 25.7% since before the pandemic.

Steve Ahlquist: Do you have a sense of what is happening to people who are not able to make their rent?

Grace Hartley: That's a bit beyond the scope of this report. We have ongoing research and we're looking into a lot of those things, but I can say that after people evicted, it can be sort of a downward spiral.

Some people go into the streets, some people have to stay with family and friends. And wherever they end up after they are evicted, it wrecks people's credit. Their name gets put into a national database where a lot of landlords, maybe not most but a lot, screen you. And once your name has been put on such a list, it can be very difficult to get your name removed. It's very, very difficult to get out of that hole. we call it a Scarlet E.

We have studies that show that people who face evictions lose their jobs at a much higher rate - not to mention all the physical and mental health impacts. We have research pointing to loads and loads of negative impacts from a single eviction.

Steve Ahlquist: When landlords raise the rent and evict, who are they finding that are willing to pay the new rents?

Grace Hartley: That's a good question. We don't have numbers or the demographics about who specifically is in these buildings. What we know is that there's a large number of people in this country who are rent-burdened, which means they're paying higher than 30% of their income. I think it's likely that people are pushing their limits a little more.

…the national trend is true of Providence, in that households with children are much more likely to be evicted or to face eviction than households that don't have children.

Steve Ahlquist: The Eviction Lab put out another paper, Who is Evicted in America, that determined, for the first time, the precise number of renters impacted by evictions. And included in that number were almost three million children nationwide. What can you say about that aspect of it?

Grace Hartley: Rhode Island is definitely in the lower half out of all the states that we studied. It's a smaller proportion of renter households with children and children evicted than the rest of the country, but the national trend is true of Providence, in that households with children are much more likely to be evicted or to face eviction than households that don't have children.

Steve Ahlquist: Do you have suggestions for how we get ahead of this? What do we do about this problem?

Grace Hartley: There's not one specific thing that can be done. There are lots of federal policies we could do, but even on a local level, there are a lot of different policies that could be enacted. The pandemic proved that providing people with rental assistance causes fewer evictions. If you are giving people more time, if you're having a moratorium on evictions or just giving people stimulus checks, providing federal assistance reduces the number of evictions.

On a more local level, zoning policy can be a huge issue. Some cities only allow for single-family homes to be in certain localities. Letting people develop and build affordable housing and more apartment buildings is a huge thing.

We've also seen a lot of local micro-policies have an effect. We have a paper that says that filing fees, even if it's a very small amount of money, can have an effect. If a landlord has to pay a certain amount of money, like $100 to the court to file an eviction eviction, filings drop. [In Rhode Island filing fees are around $80.] In a lot of places, there's no fee so landlords can just file as a method to threaten the tenant, as in, "I'm going to file against you so you'll realize I'm not kidding around and you'll pay me the money." We found that in localities where there is a small filing fee, there's a significant decrease in the amount of filings.

It's a very small measure that we've seen to be effective. But overall, nationwide, this country needs a lot more affordable housing.

Steve Ahlquist: As a state, we're working on that, but we're ten years away from making it happen in a way that will have a dramatic effect.

Other cities in the northeast, specifically Philly, Boston, and New York, cities that are much larger than Providence - are trending downward. They're seeing fewer evictions compared to the pre-pandemic average. Providence is, this month specifically, 18% up, and 7% higher than the pre-pandemic average.

Steve Ahlquist: Is there anything else I should know?

Grace Hartley: It's worth noting that Providence, as you said, is seeing a lot more filings right now.

Other cities in the northeast, specifically Philly, Boston, and New York, cities that are much larger than Providence - are trending downward. They're seeing fewer evictions compared to the pre-pandemic average. Providence is, this month specifically, 18% up, and 7% higher than the pre-pandemic average.

Boston had about 7,000 filings over the past 12 months, and Providence about 6,700. So I think that's pretty significant considering that Boston is maybe six times bigger.

Steve Ahlquist: That's ridiculous. That we're keeping pace with Boston in real numbers is just insane.

Grace Hartley: It's crazy.

Landlords seem to be becoming more and more scumlike

Truly vulgar. But what is at the core of it all?