Not just "free speech good/censorship bad" - Laura Beers is taking Orwell back from the right

“My book attempts to reclaim ... the Orwell who risked his life and [fought] against fascism in Spain - the Orwell who believed in a greater idea of social justice.”

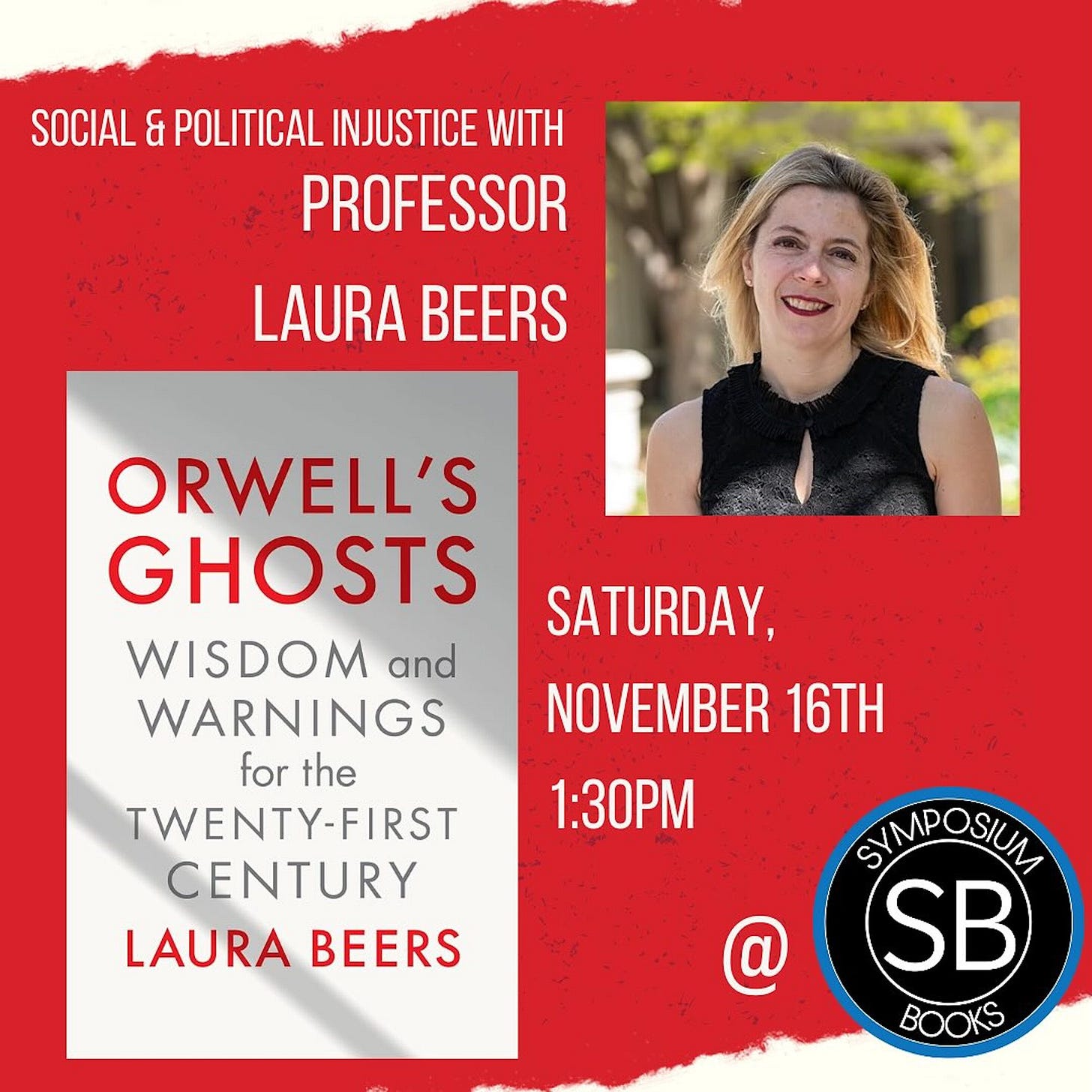

Laura Beers, professor of British history at American University, is the author of Orwell’s Ghosts: Wisdom and Warnings for the Twenty-First Century. On Saturday, Professor Beers was at Symposium Books in downtown Providence to speak about her book and kindly agreed to let me record her presentation. Kirkus describes Orwell’s Ghosts as a “determined attempt to rescue Orwell from the clutches of right-wing pundits and others who misconstrue his messages.” The Orwell that Beers uncovers, by looking into and past his most famous novels, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm, is a thinker who sees the value of government in reducing wealth inequality and other social harms.

“My book attempts to reclaim [Orwell’s] commitment to true speech and free speech. It’s also an attempt to reclaim the Orwell who risked his life and wanted to fight against fascism in Spain - the Orwell who believed in a greater idea of social justice.” - Laura Beers

Laura Beers: Talking about Orwell in the context of the last couple of weeks takes on a new valence, but this was not a book conceived in light of the recent election, but one that reflects on Orwell’s writing and its relevance to our contemporary society over the past several years. It engages with issues of disinformation and political truth both in the United States and abroad but also thinks about how reading Orwell can help us understand other issues within contemporary society, including the persistence of racial inequalities and inequalities between the West and the global south, broadly conceived, social inequality at home, and questions about gender relations and the place of feminism within the 21st century.

Many people’s initial response might be, “What can Orwell tell us about these questions? I think of Orwell as a defender of free speech.” If you read Animal Farm or Nineteen Eighty-Four, either in school or in some other context, maybe many years ago and have them vaguely remembered, that’s often how, particularly in the United States where Orwell’s other writing is less well known, how he’s remembered.

The book is not a biography. The first chapter gives an overview of Orwell’s life and puts his writing on politics and society in context to understand his writing. The book asks how Orwell’s work in the 1930s and 1940s helped us understand our contemporary political moment. It also asks how Orwell has been so misunderstood and how a better understanding of him can help us understand and prove valuable in thinking about the 21st century.

I wanted to start by reading a passage from the end of the book, relating it to the Orwell of many popular conceptions, and asking how the Orwell presented in this book seems to be such a different character than the caricatured Orwell you often hear discussed in the popular press, in the media, or if you follow Elon Musk on X.

Musk is a big Orwell obsessive, but he has a very particular understanding of who George Orwell is. I end the book by asking, “What would Orwell have thought about the persistence of tyranny and inequality alongside the apparent failure of socialism in the 21st Century?” Arguably, he would not have been surprised. Orwell wanted a better, more equal, and socially just world. At the same time, he wanted a world where the personal liberties and individual freedoms he valued were safeguarded. He believed it was necessary for the State to protect its citizens from poverty and want but that it should also secure their freedom of thought and action. For a brief moment, early in the Second World War, Orwell was overcome by an uncharacteristic, characteristic optimism that Britain could achieve the social revolution he desired without the bureaucratic overreach he feared.

His optimism quickly waned as he realized that popular support for a democratic revolution was still lacking. Some on the left viewed the Soviet Union’s command economy, an unaccountable bureaucracy, as a model for Britain.

As I said in other places in the book, he wrote Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four to clarify that the brutally enforced collectivism of the Soviet Union and its satellite regimes did not offer true equality. This flags some of the contradictions in Orwell’s writing and the contradictions of our memory of Orwell because when we think about him as a defender of personal liberties and individual freedoms, which he very much was, that part of his identity sat side by side with someone who believed that the State had a role in protecting its citizens from poverty and want and [held] a strong belief that there needed to be a social revolution to create a more just and equal society.

Here, he’s thinking not just about economic inequality but also about social inequality, the ability for human beings to see one another’s humanity and to have some sense of collective action. Because of this tension, he was nervous that the type of social revolution he hoped to see couldn’t be achieved without the protections of liberty. He emphasizes the need to protect the liberty of thought in Animal Farm, which he subtitled a fairy story but which has normally been read, particularly during the Cold War, on the level of simple analog for the Soviet Union. I don’t know how many of you read Animal Farm in school, but if you did, you probably mapped out Snowball as Trotsky and Napoleon as Stalin and went through all those ways in which it is a tale about the Soviet Union.

But it is also a broader story about how a revolution can be corrupted. I teach a course on Orwell’s writing at American University in Washington, D.C. I’ve had students who’ve come to me from other countries, including last year, a young woman whose family had immigrated from China, whose mother had always been a big fan of Orwell, seeing Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four as an analog or an allegory for her experience as a young person in communist China.

We all know Orwell, who defends free speech. This is the Orwell of Elon Musk, who wears a T-shirt that says, “What Would Orwell Think?” On the eve of the election, Musk tweeted on X, “Make Orwell Fiction Again." He read this as “we have to get rid of Biden” and [against] what he sees as the woke control of news narratives.

We saw it four years ago when Donald Trump Jr. claimed that his father’s de-platforming from Twitter, as it was then, was Orwellian cancel culture or, similarly, when Josh Hawley had his book contract with Simon and Schuster canceled after expressing his support for the January 6th rioters, if you remember that famous photo of him with the raised fist. Hawley claimed that the book contract cancellation was Orwellian cancel culture and that he was a victim. Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch, in his opinion in 303 Creative v. Elenis, claimed that it was Orwellian thought policing to make someone make a cake for a hypothetical queer wedding.

These are the ideas that Orwell stands for, such as liberty. But one of the arguments that I make in the book, which is based on a close analysis of his political writing, not only in Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four but also in Burmese Days, which was his first novel and is largely based on his own experience as an Imperial Officer after he left school. Orwell didn’t go to university. He enlisted in the Indian Police Service and asked to be sent to Burma, where his mother’s family, who were part of the white, Anglo-Indian elite, had come from.

Orwell served for six years in the Indian Police Service in Burma - Burma was part of greater British India at that point - and developed a consciousness of both the tyranny of arbitrary power, which he wielded as a representative of the police, but also of what in Burma are racial and income inequalities. [The experience] made him very conscious of inequality and arbitrary power. The first novel he wrote is about his time in Burma. I’ll read to you briefly about what I think is the essential role of that experience in forming his politics against injustice. He wrote,

"...I hated the imperialism I was serving with a bitterness which I probably cannot make clear. In the free air of England, that kind of thing is not fully intelligible. To hate imperialism, you have got to be part of it. Seen from the outside, the British rule in India appears - indeed, it is -benevolent and even necessary ... But it is not possible to be a part of such a system without recognizing it as an unjustifiable tyranny."

This opposition to tyranny manifested in his critiques of the Soviet Union and Stalinism, which had an even earlier origin. It is directed against his government, which he sees as an agent of while serving in the Indian police for six years. His writing is informed, not just in those last two novels, with this ongoing critique of tyranny. You see that in particular in his writing on the Spanish Civil War. The irony about his book on the Spanish Civil War, Homage to Catalonia (which is one of my favorite of his works), is that he goes to Spain at the very end of 1936 and spends the first six months of 1937 in Spain fighting for the Republic against Francisco Franco’s insurrection.

Orwell is fervently anti-fascist from the mid-1930s and very supportive of the war against Hitler. He believed, when he went to Spain, that he was dealing a blow to fascism by supporting the Republican government. But while there, he ended up, just by luck and through personal connections, volunteering with a small left-wing group, the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), whose political thinking was opposed to Franco and supportive of the democratically elected government of the Spanish Republic. The Party differed from the mainstream line that the only purpose of the war was to defeat Franco. They also saw a social revolution as something they hoped to get out of this conflict. When the Stalinist regime in Russia started lending money, arms, and materials to the Spanish government, Stalin’s Russia started to play a much bigger role in [determining] the policy direction for the Republic. It said they needed to focus solely on defeating Franco and not get distracted by social change and revolution. It’s not the point.

Under the direction of Stalin, the Spanish Republic started to repress groups like the POUM violently and also the anarchists who wanted to change society as well as to defeat fascism, and didn’t see this as an either/or. Many of Orwell’s friends ended up in prison - some of them ended up shot. Orwell fled with his wife, who had come with him to Spain, across the Pyrenees shortly before he would have been arrested himself. Orwell came home and wrote Homage to Catalonia, intending to expose, for those on the left who support the Republic at home, the role of the Soviet Union in corrupting what he saw as a just attempt to not only defeat fascism but create a better Spain after the Civil War is over.

He can’t get his book published because back home in Britain, those on the left don’t want to hear about how many shades of gray there are within the Republican coalition. They want to hear, and Orwell states this. However, he buries it deep within Homage to Catalonia, “at the end of the day, I still think it would be better for Franco to lose and the Republic to win despite all this nastiness taking place within the Republican coalition.”

Those at home on the left are worried that not having the story look black and white, revealing nuance, and revealing the problems within the left-wing coalition will sully support for the Republic against Franco. Therefore, they don’t want to hear it. Effectively, they cancel Orwell. His publisher cancels him like Simon and Schuster canceled Josh Hawley. This was not Orwellian dictatorship as Hawley presented it, and it didn’t mean that Homage to Catalonia wasn’t published. It meant that Orwell had to find another smaller publisher. He published the book. It was not Stalinism. He was not thrown in prison, and he was not erased. He still could exercise his speech, but he didn’t have as large an audience as he would have if his initial publisher, Victor Gollancz Ltd, had published his book and helped distribute it through the networks of the left book club.

This was when Orwell was forced to confront what was a major tension for him. On the one hand, his belief in socialism and his belief that the Republic needs to win and Franco needs to be defeated. On the other, there is his belief in the importance of truth and speaking his truth. He decides it is more important to tell the truth about what he saw happen in Spain, even if it muddies the waters of people who would unquestionably support the Republic. There’s that tension between free speech and true speech. Orwell believed in free speech, but he also believed in the importance of speaking the truth.

You can see that played out later in his work when he writes in Nineteen Eighty-Four that the Thought Police have arrested Winston Smith and is being tortured in the ironically named Ministry of Love. The form of his torture is that O’Brien, his interrogator, is trying to force him not only to say but to believe that two plus two equals five. Orwell said liberty is the right to say that two plus two equals four. It is not, as Kellyanne Conway would say, the right to assert a truth or an alternative fact. There are no alternative facts. There is the truth that two plus two equals four, and there is the lie that two plus two equals five. The Orwellian dystopia Orwell presents is one in which people say that two plus two equals five. This often gets lost by those, particularly within certain elements of the right, who defend Orwell as a tribune of free speech.

Orwell does believe in free speech. He wouldn’t support anyone imprisoned for saying anything, but he also believes that truth matters. My book attempts to reclaim that commitment to true speech and free speech. It’s also an attempt to reclaim the Orwell who risked his life and wanted to fight against fascism in Spain - the Orwell who believed in a greater idea of social justice.

On the one hand, those beliefs emerged from his time in Burma and his view of himself as an oppressor within an imperial context. However, they can also be traced back to his writing on social investigation in Britain. Two of his nonfiction works were Down and Out in Paris and London, the first book he published as a young man, and The Road to Wigan Pier, a later piece of investigative journalism.

In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell was sent on commission by his publisher to go up to the northwest of England in 1936. After seven years of depression and after an even longer period of economic slump in the United Kingdom before the Great Depression began in 1929, you had people who, for a generation, have been out of work, and you have people working in coal mines and not being paid a living wage for doing backbreaking and dangerous labor. Orwell records the lived experiences of these coal miners. Orwell himself is six foot four. He goes down and hunches and crawls around in the mines, which is a particularly difficult experience given his height. He talks truthfully about the miners’ experiences and the housing market and what it means to have a situation of housing scarcity combined with slum housing in a way that makes people desperate for any roof over their heads, even if that roof is completely inadequate.

If any of you have read Matthew Desmond’s Evicted, which discusses the current housing crisis and living conditions in slum parts of Minnesota, he focused on a lot of the same tropes that Orwell vividly describes - slum housing in the northwest of England. But Orwell also attempts to think honestly and give agency and humanity to those he’s writing about instead of condescending to them. In The Road to Wigan Pier, he vividly writes about the way that want, deprivation, and inequity can lead people to make choices that the middle-class audience of leftist reformers for whom he’s principally writing might fail to understand. Orwell writes, for example, about the ways that people who are living on public assistance might choose to spend their money not on a basket of healthier groceries as some of the members of his reforming socialist circles in London would think they should, but on what he refers to as tasty treats. How do you make sense of the fact that people with very little would spend what money they had buying chips (or fries, as we would call them in the United States) rather than raw potatoes?

In writing that way about the working class, whom he interviewed and lived amongst, he’s giving them a type of agency and respect for their thought processes that social reformers in his time, and I think arguably social reformers in the 21st century, often have failed to do. Think of Ted Cruz running for president eight years ago, saying that if he won, fries would be back on student menus in cafeterias. On the one hand, it seems absurd as a campaign pitch, but on the other hand, it spoke to a sense of condescension. Who is the government to tell us and our children what we should be eating when so much of our lives are dictated to us by choices we cannot make?

Orwell’s writing is particularly useful for those of us in the 21st Century who are thinking about communicating across class differences and seeing each other’s shared humanity. He does his best to meet people where they are, give them the dignity of their decisions, and engage with them - not the terms of who he thinks they should be or who the left-wing elite in Britain in the 1930s thought they should be.

My book is fundamentally about using Orwell to think about the 21st century. When you get beyond Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm and a simplistic “communism bad/free speech good” to a more nuanced appreciation of Orwell’s political thought, much remains useful for thinking about our current political moment.

I don’t know if anyone here has read Anna Funder’s Wifedom, which came out a year or so ago, which was a novelistic retelling of the life of Orwell’s first wife, Eileen Blair, mixed with musings on Funder’s own experience as a sort of somewhat thwarted feminist and mother. She makes the argument that Orwell was a misogynist and a bad husband. Orwell has [been subjected to] a series of critiques about his gender politics - both recently by Funder and over the years by Second Wave or Women’s Liberation Feminists in the 1980s.

My book engages with the question of what we do with someone who very much in his own time identified as on the left and who, after he passed away, particularly in Britain where his work had been known for longer, was associated and eulogized with the left - but was very much not a feminist? To take the most famous example of his anti-feminist thought, in The Road to Wigan Pier, he writes about how crank lefties drive normal decent people out of left-wing politics. He has a list of crankish lefties that include nudists, fruit juice drinkers, and sandal wearers. He has a long list of people outside the mainstream - and he ends with feminists. There is place after place in Orwell’s writing where you can see the casual incorporation of sexual violence, the use of demeaning language when talking about women, and the lack of agency or intelligence that is ascribed to female characters that make it very hard to conclude that Orwell was anything other than quite hostile to feminism and women’s equality - even within the context of his time.

I also discussed this in one of his novels, Keep the Aspidistra Flying, in which the decision not to have an abortion plays a central role. Orwell writes a discussion of abortion, which does not take into account ideas of women’s agency and women’s bodily autonomy, which at the time in the 1930s were very much being discussed amongst the British left. In particular, the Abortion Law Reform Association was started by feminists in Britain in the 1920s, and there is a discourse that relates abortion rights to women’s bodily autonomy. That is not something that Orwell engages with in his novel about the decision to not have an abortion. I think about what that says in terms of our knee-jerk assumption that feminists are of the political left and how that Venn diagram looks in practice.

When I was writing the book, I was thinking that while most feminists identify with the political left, you see many on the political left today who, like Orwell in the 1930s, did not identify as feminists. But in the aftermath of the most recent election, I’ve been increasingly thinking about how you can identify as a feminist, or at least have a strong feeling that the sense of women’s right to bodily autonomy, and not identify as progressive. Looking at those exit polls in places where abortion had been on the ballot - in states across the United States you see significantly more people willing to vote for a constitutional right at the State level to protect a woman’s access to abortion than were willing to vote for the Democratic Party in the presidential election.

The chapter on Orwell and gender discusses how reading Orwell was a vehicle for rethinking the connection between feminism and left politics. It also argues that if we want feminists to be accepted, be part of the left, and identify with the left, men who consider themselves leftist but not necessarily feminist or aren’t seriously engaging with feminist ideas must be brought into a different conversation.

That is how the book attempts to use Orwell as a vehicle for thinking about the 21st century - by going back into his writing and asking what more we can get from it other than free speech good, censorship bad, which is something Orwell believed. He believed “free speech good/censorship bad,” but his writing offers us much more than that.

Also, despite my sense of “ick” about Orwell’s gender politics, the book is a love letter to Orwell in many ways. I very much hope that reading this book encourages people to go back and read his books once again or for the first time, and to read his excellent political essays, of which there are many, and think about what his writing can offer you because he is a rich writer, an excellent stylist and someone who I’ve come back to again and again over my career. I now teach a course at American University for Undergraduates where we read all of Orwell’s work across the semester as a vehicle for thinking about the early 20th century. My students are always making connections between the past and the present, which ultimately encouraged me to write this book.

Question: I’m curious about people who align with Orwell but support the dissemination of misinformation.

Laura Beers: This is where we get a simplistic, reductionist reading of Orwell, which calcified amongst the political right during the Cold War when Orwell was recast as a cold warrior. He died in January 1950, in the very early days of the Cold War, and he was vehemently anti-Stalinist, but his politics are more those of a liberal anti-communist. He supports Clement Attlee’s Labor government, which was elected in 1945, even though he refers to Big Brother’s regime in Nineteen Eighty-Four as Ingsoc for English socialism. He’s very explicit. This is a dystopian nightmare scenario and is meant to suggest that any system can be corrupted and fall, even the current government, which he supports. It is not a commentary on what is wrong with Attlee. During the Cold War, partly because Orwell died as early as he did, it became easy to appropriate him. He can’t speak out. He is reduced to an anti-Stalinist. You see this in the cartoon version of Animal Farm, which was produced with CIA funding and used as a Cold War vehicle for educating children about the evils of Russia.

If what you’ve taken from Orwell is that communist regimes are evil and repress free speech, and free speech is a value of democracy, then I think you can see Orwell as championing the right to say that two plus two equals five. But that is not his message. His message is as much about truth as it is about freedom of speech, and that’s one of the things I try to draw out in the book.

I say in the introduction that I can tell from lived experience how Josh Hawley and Donald Trump Jr., likely in the waning days of the Soviet Union, were taught Animal Farm in school. If that is where you stop with your Orwell, it’s not hard to see how you can get the view that Orwell’s politics are to defend free speech stop. I suggest that there’s significantly more nuance to the story.

Question: Do you know where Orwell was on the New Deal or the welfare state?

Laura Beers: He is very supportive of the Attlee government, and in some ways, he thought they hadn’t gone far enough. During the Second World War, he wrote his most optimistic book, a short book called The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius. In it, he advocates for the redistribution of incomes by the State through taxation so that the wealthiest has no more than 10 times the income of the poorest member of society. He also advocates nationalizing mines, railroads, and many other industries. He sees a significant role for the State.

How he saw the Attlee government as lacking was not that it introduced steeply progressive taxation. In Britain, you had upper tax brackets up to 75% in the immediate aftermath of the war. Nor that it nationalized major industries and created various welfare protections - in terms of a universalized national health service and universalized pension system in many ways analogous to Social Security in the United States, but they were focusing only on the structural elements and not on the more fundamental elements of social equality and breaking down class structures.

Orwell was very disappointed about the continuation of private schools. He went to the poshest of the posh private schools. He went to Eaton, where Boris Johnson and David Cameron, two recent British Prime Ministers, went, where Britain’s elites are still produced. But Orwell believed private schools should be abolished because they were vehicles of class snobbery. Because he was so conscious of his class snobbery and how much work it had been to try to unlearn it as an adult, he thought it was really important to break down those social barriers. He writes that middle-class children in Britain - and here he means upper-middle-class children in Britain - are taught from infancy that the working classes smell.

He’s not saying that this is a class prejudice that is imprinted on you quite young, and if we’re going to have an equal society, that kind of behavior has to be unlearned. He thought the Attlee government didn’t go far enough in that they did all these structural things at a high level. Still, they don’t change hearts and minds about how people see each other and how snobbery separates people.

He supported structures like the New Deal, which was implemented in Britain at the time, and wished that the changes in social and economic structures had been more extensive.

much appreciate the space given to analyze Orwell, though I'm one of the many limited to 1984, Animal Farm.

I do appreciate Orwell as an anti-fascist, anti-Stalinist, anti-imperialist, anti-class privilege, and as a free speech and true speech advocate. That he was anti-feminist does not surprise me, that is so mainstream, even on the left - I remember the phrase during the turbulent 60s "the position of women in the movement is horizontal" No accident black men got the vote before any woman, a black President before any woman - note with the same Party, Obama and Biden win, Clinton and Harris lose.

The right-wing may have appropriated Animal Farm but there is a subversive message about religion - the ruling farmers hire a crow to tell the animals to work hard, they will be rewarded after they die. At the revolution the crow is banished, but brought back with a similar message by the pigs who took over, the same motive as the farmer. Pie in the Sky when you die!!