Justin Meszler: White Supremacy in the Soil: Race, Place, and Power in Pawtucket

"The disempowerment of and disinvestment from the Woodlawn community have led to the present political environment that shuts out the voices of Black and Brown residents..."

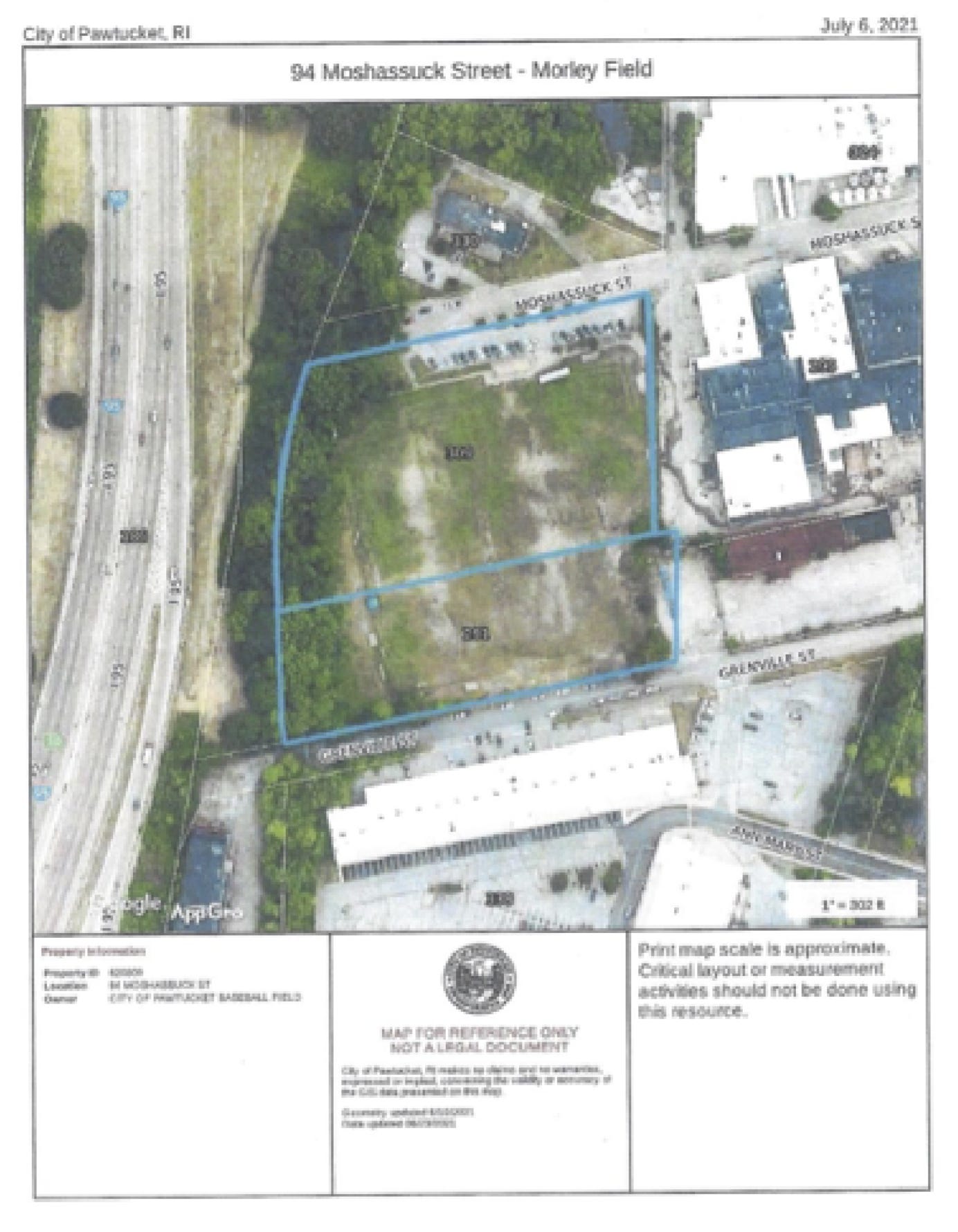

“It was either play in the streets, or Morley Field - so that’s where we went to play soccer. It has personal meaning to me,” Pawtucket City Councilor Clovis Gregor reflected. “My kids play soccer there, practice different games, and all kinds of stuff over there. For it to just be gone is sad, especially since they’ve been neglecting the field for well over a decade” (Clovis Gregor, pers. comm., May 16, 2023). Flipping through a thick manila folder of letters, appraisals, and maps, Gregor recounted his nearly two-year-long effort to fend off the destruction of Morley Field. Adjacent to Interstate 95 (I-95) and a shopping plaza, Morley Field sits by the Moshassuck River in the Woodlawn neighborhood of Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Created in the 1970s from a combination of federal grant-purchased land and gifted land, the 5.1-acre park is one of the only major public green spaces in the poor, predominantly Black and Brown Woodlawn community (Ahlquist 2022).

However, in the spring of 2021, developers JK Equities approached the city about paving over Morley Field to create a parking lot. JK Equities had acquired a neighboring abandoned textile mill with plans to build a warehouse distribution center. In August 2021, with the unenforceable promise of job creation for the community, the Pawtucket City Council voted to sell the land to the developers (Cowperthwaite 2022). Hiring a third party to perform environmental testing on Morley Field, JK Equities alleged hazardous contamination in a section of the park. In June of 2022, the city fenced off Morley Field from residents (David Clemente, letter to Pawtucket City Council, June 29, 2022). According to Councilmember Gregor - who represents the district that includes Morley Field—and confirmed by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), the city chose to fence off the entire park from residents despite supposed contamination levels not necessitating its immediate shutdown. Community members have since protested outside the field, testified at city hearings, and appealed to state authorities to prevent the current plan from moving forward. Legal issues have recently complicated the sale, but the city has made clear that it still intends to destroy much of the park (Ahlquist 2023).

Race and racism are central to understanding the present physical and political dynamics of this neighborhood. Textile industrialization along Rhode Island’s rivers, construction of the I-95 highway in the 1960s, white flight from Pawtucket, suburbanization, and deindustrialization have all shaped the neighborhood and present political climate. These processes produce the circumstances with Morley Field through racialized spatial control and community neglect. Further, the debate over Morley Field is a stark example of the spatialization of race and racialization of space, and the current differing stances over the future of the park can be explained through theories of the white spatial imaginary and black spatial imaginary. The city’s continued efforts to destroy Morley Field reflect the cyclical nature of past discriminatory policies: The effects of past racism justify new racism. Working within the white spatial imaginary, the city administrators and developers warp the racialized history of the area to justify the sale of the park, continuing a long history of white Rhode Islanders falsely championing racial justice while further exacerbating racist outcomes. The controversy over the space of Morley Field, emerging from historic racialized city planning and the disempowerment of community voices, is an issue beginning and ending with race. Working to undo these systemic effects through the black spatial imaginary provides a blueprint forward that centers and elevates community voices.

Racial History of Pawtucket

Industrialization birthed the Rhode Island urban environment alongside the Narragansett Bay and rivers, tracing back to cotton and wool textile factories in the late eighteenth through mid-nineteenth centuries (Marlow, Frickel, and Elliott 2020, 1097). Produced in the South with enslaved labor, cotton shaped the initial Rhode Island economy and industrial landscape. Between 1790 and 1860, industrialists opened nearly three hundred textile firms in Rhode Island (Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, 2021). The creation of Rhode Island’s urban spaces was rooted in the exploitation of enslaved Black people. However, some abolitionists intentionally embraced this industry in an effort to detach from slavery. In 1789, Moses Brown, founder of the Providence Abolition Society, created a textile manufacturing firm to shift the local economy away from the explicit trafficking of enslaved people. He would go on to finance Slater Mill, the first water-powered textile mill in the country, located on the Blackstone River in soon-to-be Pawtucket (National Park Service, 2022). While exacerbating slavery’s outcomes - the enrichment of white elites at the expense of Black lives - Moses Brown sought to absolve himself and Rhode Island from the immorality of Southern slavery. John Brown, Moses’ pro-slavery brother, tauntingly wrote in the Providence Gazette, “This is most certainly a laudable undertaking, and ought to be encouraged by all, but pause a moment - will it do to import the cotton? It is all raised from the labor of our own blood; the slaves do the work. I can recollect no one place at present from whence the cotton can come, but from the labor of the slaves” (Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice, 2021). The creation and initial growth of Rhode Island’s urban industrial core - the wealth of Rhode Island’s white elite - was intrinsically tied to slavery, despite some actors’ intentional distancing of the two. As Rhode Island authorities went on to reject slavery and de jure racism, the phenomenon of obscuring explicit connections to race while welcoming racism’s benefits would continue to emerge among the affluent, white populace.

Population and manufacturing continued to grow in Rhode Island into the twentieth century. The factories soon turned from cotton to steam engine construction, costume jewelry, and electroplating. By the 1960s, these industries polluted the rivers with heavy metals and degraded the land with toxic contaminants (Marlow, Frickel, and Elliott 2020, 1098). According to the United States Census, Pawtucket’s population was nearly entirely white in 1960 (Map U.S.A Project, n.d.). However, much would soon change in this environmentally degraded landscape. Urban growth created congestion, prompting calls for improved infrastructure. With the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 creating plans to fund and build interstate highways across the country, Rhode Island voters approved highway expansions to address stifling traffic issues (Mooney 2022). The creation of these highways not only displaced residents and businesses but also contributed to the deindustrialization of urban areas. Better highway infrastructure drove down transportation costs, allowing manufacturers to move facilities to suburban areas and eventually out of state. Between 1960 and 1980, the manufacturing industry in Rhode Island’s traditional industrial core fell by 20 percent (Marlow, Frickel, and Elliott 2020, 1098-1099).

As these opportunities left, so did the white people. Eminent domain and the condemnation of property displaced more than 1,100 families in Pawtucket as officials mapped out I-95 throughout the state (Mooney 2022). Through this process and the resulting newfound transportation, the construction of I-95 reorganized residential neighborhoods. The number of residents in Rhode Island's industrial core also fell by around 20 percent during that time period as suburbanization intensified. This restructuring of industry and people led to vacant properties and a dearth of good-paying jobs. Who would populate this disinvested and environmentally hazardous space? More racial and ethnic minority groups soon moved into these neighborhoods. Many of these groups, especially Latinx populations, were originally attracted to the area to provide cheap labor in the textile mills (Marlow, Frickel, and Elliott 2020, 1099).

Despite the abolition of slavery, racist systems and their benefits to white people remained. Across the country, racial redlining, restrictive covenants, predatory lending, and other practices led to white flight, the restriction of movement of racial minorities, and sharply segregated neighborhoods. Rhode Island was no exception (Grigoryeva and Ruef, 2015, 833). Today, Pawtucket is 43 percent non-white, while many suburban areas outside the city are 80-90% white (Map U.S.A Project, n.d.). In the Woodlawn neighborhood, one-fourth of residents are non-Hispanic white, a third are Black, and one-fourth are Hispanic (Statistical Atlas, n.d.). Abandoned by manufacturing and suburbanization, these neighborhoods and their residents bear the environmental consequences of past urban planning. A 2020 study found that the proportions of Black and Latino residents in Rhode Island have become increasingly likely to live in former manufacturing areas with legacy pollutants over the past 30 years (Marlow, Frickel, and Elliott 2020, 1109). Distancing themselves from the consequences of racially discriminatory practices, affluent white communities passed the harmful environmental legacies of Rhode Island’s urban industrial core onto racial minorities. This distance from the negative impact of racist systems, similar to the investment in textile mills in the 1790s, obfuscates race as the driving force behind these inequalities in environmental degradation and poverty.

These processes directly impact the physical condition of Morley Field and the Woodlawn neighborhood. A 1974 environmental impact statement describes the area of the Woodlawn Athletic Field (Morley Field): “The area surrounding this parcel is predominantly industrial in character…The site is a former landfill, and available information indicates that the surface deposit of miscellaneous fill of tin, bricks, paper, and other debris extends between 10 and 20 feet in depth” (Michael Cassidy, letter to Department of Natural Resources, 1974). From the origination of Morley Field, the space has been racialized by the harmful environmental legacies of Rhode Island’s industry.

Morley Field as Racialized Space

Morley Field and the Woodlawn neighborhood can be understood through both these forms of systemic racism and also their effects on cultures and perspectives. George Lipsitz, a Professor Emeritus of Black Studies and Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, theorizes that historical policies like those experienced in Pawtucket contribute to the spatialization of race and racialization of space (Lipsitz 2007, 12-13). Space, developed and restricted by these historical racial policies, forms varying physical attributes that influence perceptions of race. Race, in shaping the geographies of neighborhoods, their physical attributes and conditions, and their inhabitants, perpetuates ideas about certain spaces and their functions and values.

Lipsitz identifies the white spatial imaginary and black spatial imaginary as two opposing conceptual models of space. Formed by housing policies and legal racially discriminatory restrictions, the white spatial imaginary prioritizes the exclusivity and augmented exchange value of the land. Under this paradigm, the maintenance of white homogeneous spaces and the monetary and private value of property are central to understanding space. The black spatial imaginary, while influenced by the same historical processes, is antithetical to the white spatial imaginary. Emerging from racial disempowerment and a historical inability to control the exchange value of land, this imaginary focuses on the augmented use value of properties—centering community needs in constructing the value and purpose of space (Lipsitz 2007, 13-14).

The difference between the white spatial imaginary and the black spatial imaginary leads to conflicting perspectives on the value and racial meaning of the 5.1 acres of Morley Field. While city officials view the land in terms of monetary opportunity, local residents see the space for its value to the community. JK Equities’ website describes the project site as a “10+ acre vacant textile mill with excess land across the street” (JK Equities, 2022). Presumably, this “excess land across the street” is Morley Field. This view of public recreational land as “excess” epitomizes the augmented exchange value understanding of space defined by the white spatial imaginary. The land’s primary purpose, in the developers’ view—is its commercial worth as private property. The influence of the white spatial imaginary extends not just to the developers but to the city as well. In January 2020, even before this controversy, Councilmember Gregor claimed that the finance director of the city commissioned an appraisal of Morley Field. “Why would you appraise the field if you’re not looking at selling it?” questions Gregor (Clovis Gregor, pers. comm., May 16, 2023). Ideas around the augmented exchange value of land are paramount to the city administration and developers’ understanding of Morley Field.

However, community members view the green space in a much different light. According to Lipsitz, from enslavement to segregation to public buses to prison, the restriction and control of racial minorities in space create “a powerful black spatial imaginary, a socially-shared understanding of the importance of public space and its power to shape opportunities and life chances” (Lipsitz 2007, 17). The city’s control over Morley Field’s usage and its suitability for sports games, community heritage events, and leisure fosters the black spatial imagination. Testifying in front of the city’s planning commission last August, Pawtucket resident Tatiana Reis argued, “379 parking spots does not equate to the memories of the children in our community. We use Morley Field for Pop Warner games, we use it for exercise, we use it to just hang out, put our blankets down and chill” (Ahlquist 2022). Assigning greater value to the community’s children over the proposed parking spots, Reis rejects the notion of augmented exchange value in favor of the space’s potential use value. At a rally last November, then-Representative-elect Cherie Cruz echoed similar sentiments: “We can no longer allow city leaders to ignore and neglect the needs of the families in Woodlawn and sell our kids’ resources and opportunities to corporations—corporations that do not have the health and wellbeing of our community at heart” (Ahlquist 2022). Esteeming community needs over corporations, Reis and Cruz’s sentiments operate firmly within the black spatial imaginary. This powerful black spatial imaginary, counter to the city and developers operating in the white spatial imaginary, envisions a collaborative space that centers the community’s usage and desires for the land.

Spatialization of Race through Morley Field

This interplay between race, space, and power in the neighborhood even shapes people’s understandings of reality and the physical conditions of Morley Field. The Woodlawn community and Morley Field may be more easily viewed as harboring hazardous materials and being dirty and dangerous due to the spatialization of race. Historic stereotypes of racial minorities as contaminated and unclean—ideas justified by and for racial discrimination and segregation - influence the perception of Black and Brown neighborhoods and their inhabitants. Through these pseudoscientific beliefs around dirty and diseased populations, space is racialized. The emergence of Black neighborhoods as toxic dumping grounds is a consequence of spatial control and racist depictions of Black people as toxic sites (Merchant 2003, 381). Despite independent outside testing later revealing no contaminants on one lot of the park, the city maintains fences around Morley Field as “a necessary step in order to protect the public from the hazardous materials which were uncovered by environmental testing” (Soil Test Report, 2022). JK Equities’ clear incentive in finding contaminants to compel the city to sell the land places their environmental testing in doubt. However, city officials seem to ignore these concerns in service of justifying the sale of the land. Officials may be influenced by spatialized racial stereotypes to more easily believe Morley Field and Woodlawn to be contaminated and hazardous. As a consequence of political expediency and the spatialization of race, the results of JK Equities’ biased environmental testing went largely uninvestigated by city administrators.

Racialized Spatial Control and Disempowerment

The current political dynamic of the city governing the space of Morley Field without community power perpetuates a long history of the regulation of spaces inhabited by communities of color. The act of fencing off Morley Field, an unnecessary measure to its sale, reasserts city power over the community’s spaces. However, city planners have emphasized that the decisions over Morley Field have been open to community involvement. In a letter to the city council last August, Director of City Planning Bianca Policastro identified “eight public meetings regarding the redevelopment of Morley Field” and stated that the planning “has been an open and public process in which residents have been encouraged to engage with the department” (Policastro, letter to Pawtucket City Council, 2022). Additionally, last October, since part of Morley Field was originally gifted to the city, state law forced the city to revise the initial sale to pave over only 60% of Morley Field (Ahlquist 2022). Framing this revision as a “compromise” with residents, the city council passed a resolution to work with the Woodlawn Neighborhood Association on reopening recreation in the remaining land (Cowperthwaite 2022). Yet, in each of these public meetings and situations, community participation does not necessarily signify community power.

Many of these public meetings featured testimony - sometimes exclusively - from residents and concerned citizens against the proposed plans (Ahlquist 2022). Additionally, according to Councilmember Gregor, the Woodlawn Neighborhood Association never had any interest in Morley Field, and some of its membership, including leadership, works for the city. “They [the city] didn’t want public input,” Gregor asserted. “They just wanted to get it through. This organization [Woodlawn Neighborhood Association] was going to do whatever the administration wanted” (Clovis Gregor, pers. comm., May 16, 2023). The association’s 2023 non-profit corporation annual report identifies its mission to “educate the residents of Woodlawn on minimum housing standards and building codes” (Rhode Island Department of State, 2023). The city’s delegation of some responsibilities to this organization, which does not prioritize community environmental justice or empowerment, continues a long history of community neglect. Neither this organization nor the city’s public meetings were conducive to empowered community participation. Further, this disempowerment is only possible through the racialized political and geographic landscape. At a rally last November, Black Lives Matter Rhode Island PAC Executive Director Harrison Tuttle asserted, “If this were in Western Cranston, or if this was in Warwick, or a more affluent area…would this be happening? It’s because this is a historically Black and Brown area, it’s because we have lower economic folks here” (Ahlquist 2022). Asked how Morley Field was a matter of racial justice, Councilmember Gregor put plainly, “Well just look at where this is happening” (Clovis Gregor, pers. comm., May 16, 2023). Without meaningful community control, the fencing and paving of Morley Field perpetuate racial minority disempowerment and spatial control.

Feigning Racial Justice

Over two hundred years later, a dynamic reminiscent of Moses Brown’s cotton textile manufacturing firm is repeating. Justifying the destruction of Morley Field in terms of economic racial justice arguments, city officials employ the legacies of racism to produce further community harm. City councilors and Pawtucket Mayor Grebien have emphasized the potential creation of hundreds of good-paying jobs in the community as a result of this deal. However, while the city administration may have reached an informal understanding with JK Equities about the economic benefit to the neighborhood, this promise is unenforceable (Ahlquist 2022). The number of jobs and prioritization of community members is not guaranteed in the purchase and sale agreement (Clovis Gregor, pers. comm., May 16, 2023). Even if it was, JK Equities may not have any power over the employment practices of the industrial tenants who would occupy the distribution center. This false assurance of economic revitalization capitalizes on the neighborhood’s poverty from past racialized deindustrialization and community neglect. Also, this instance again demonstrates how the white spatial imaginary pervades the city’s approach: administrators frame the value of land in terms of its economic usage to the neighborhood.

Moreover, this approach leads to additional environmental destruction, further worsening the effects of historic racial discrimination. Advocates identify the inevitable worsening of the urban heat index in the area due to additional pavement and concrete (Ahlquist 2023). Also, the construction of the warehouse distribution center has led to the excavation of harmful materials on the property. In a letter to the city zoning director, Councilmember Gregor alleges that the site’s containment measures are “non-existent or otherwise non-conforming or cursory at best. The various stockpiles of contaminated soil, bricks, concrete slabs, construction materials, and debris, excavated from the site, are all fully exposed and uncovered” (Gregor, letter to Director of Zoning & Code Enforcement, 2023). In constructing this new facility, the developers are further contaminating and polluting the environment. This twisted logic of justifying their harmful activities by alleging hazardous materials in Morley Field is reminiscent of abolitionists investing in cotton mills while rejecting the horrors of slavery. In both cases, the perpetrators of systemic racism twist antiracist values for their economic benefit.

A Way Forward

In Pawtucket, white supremacy is in the soil, whether that includes physical pollutants or not. The disempowerment of and disinvestment from the Woodlawn community have led to the present political environment that shuts out the voices of Black and Brown residents. Supposed solutions promoting economic racial justice, advanced by developers and city administrators, operate within the white spatial imaginary and perpetuate racialized spatial control over Woodlawn residents. Through the area’s extensive history of racial discrimination and community neglect, Morley Field has been racialized and race has been spatialized. The debate over the future of Morley Field exemplifies these continued systemic injustices and dynamics.

However, the black spatial imaginary - approaching Morley Field through its communal value - illustrates a path forward that disrupts racial disempowerment. Reinvesting in green space, valuing sports practices over parking spots, and ensuring an empowered community voice in the decision-making process are crucial steps to disassembling the racist structures and paradigms that govern the current situation.

Appendix I: Map of Morley Field (Lots 309 and 291)

Map provided by Clovis Gregor, May 18th, 2023

Works Cited

Ahlquist, Steve. “Battle for Morley Field: community fights to save green space from development.” Uprise RI, April 12, 2023.

Ahlquist, Steve. “Pawtucket continues plan to permanently shut down Morley Field.” Uprise RI, October 6, 2022.

Ahlquist, Steve. “Pawtucket moves to eliminate remaining green space in an environmental justice community.” Uprise RI, April 17, 2022.

Allen, Armstrong, Azfar, et. al. “Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice.” Last modified 2021.

Cassidy, Michael D. 1974. Environmental Impact Statement of Woodlawn Athletic Field, April 17, 1974. Document provided by Clovis Gregor.

Clemente, David. 2022. Letter from David Clemente to Pawtucket City Council, June 29, 2022. Document provided by Clovis Gregor.

Cowperthwaite, Wheeler. “Sale of Morley Field in Pawtucket hits roadblock as residents speak out against plans.” The Providence Journal, September 21, 2022.

Dunn, Christine. “History of discrimination led to housing segregation in R.I.” The Providence Journal, June 17, 2015.

Gregor, Clovis. 2023. Letter from Clovis Gregor to Director of Zoning & Code Enforcement, April 26, 2023. Document provided by Clovis Gregor.

Grigoryeva, Angelina and Ruef, Martin. 2015. “The Historical Demography of Racial Segregation.” American Sociological Review 80, no.4: 814-842.

JK Equities. “Blackstone Distribution Center, Pawtucket, RI.” Accessed May 19, 2023.

Lipsitz, George. 2007. “The Racialization of Space and the Spatialization of Race: Theorizing the Hidden Architecture of Landscape.” Landscape Journal 26, no. 1: 10–23.

Map U.S.A Project. Accessed May 19, 2023.

Marlow, T., Frickel, S. and Elliott, J.R. 2020. “Do Legacy Industrial Sites Produce Legacy Effects in Ethnic and Racial Residential Settlement? Environmental Inequality Formation in Rhode Island’s Industrial Core.” Sociological Forum 35: 1093-1113.

Merchant, Carolyn. 2003 “Shades of Darkness: Race and Environmental History.” Environmental History 8, no. 3: 380–94.

Mooney, Tom. “How Interstate 95 became integral to life in Rhode Island.” The Providence Journal, August 11, 2022.

National Park Service. “Slater Mill.” Last modified August 31, 2022.

Policastro, Bianca. 2022. Letter from Bianca Policastro to Pawtucket City Council, August 19, 2022. Document provided by Clovis Gregor.

Rhode Island Department of State. “Entity Summary.” Accessed May 19, 2023.

Soil Test Result for Morley Field. Soil test Report, October 25, 2022. Document provided by Clovis Gregor.

Statistical Atlas. “Race and Ethnicity in Woodlawn, Pawtucket, Rhode Island.” Accessed May 19, 2023.

Excellent job. The only ting I would quibble with is that the deindustrialization of Pawtucket and RI in general began in the 1920;s essentially as soon as automobiles, trucks and electricity, made it possible to move out to the suburbs and away from rivers. About 1890 there was a burst of factory building in urban RI, but by the time it was time to build the next generation of factories, they had headed for the South for cheap labor and the suburbs for big one floor factories instead of multi story buildings along the rivers and rails.