Just-cause eviction protections do what they are intended to do without negative impacts

"The first recent studies have shown that just-cause eviction legislation meets its stated goals," said Dr. Molly Richards. "It leads to decreased evictions and eviction filings."

Dr. Molly Richards addressed the special legislative Commission to Study the Residential Landlord and Tenant Act to present the best data on the effects of just-cause eviction protections. Just-cause eviction protections help renters stay in their homes by preventing arbitrary, unfair, or retaliatory eviction, and the legislation is opposed by the Rhode Island Coalition of Housing Providers, the landlord lobby.

I’m presenting Dr. Richards’ testimony here, edited for clarity:

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: I’m from the Boston University Center for Innovation in Social Science and the Initiative on Cities, where our focus is supporting evidence-based policymaking. I’m also a resident of East Providence. I’m here today to share my research and expertise on housing and homelessness. My colleagues have done some work evaluating the impact of just-cause eviction policies across the United States.

I want to overview some national trends in investor-owned rental housing. I think it’s essential to show what we know. Across the country, there’s growth in corporate and investor-owned rental housing. With that, we’re seeing higher eviction rates across the country, more rapid rent increases, and greater use of miscellaneous fees across metropolitan areas. Scholars in urban studies, social science, and economics have started to document that landlords are becoming less responsive to tenant requests for maintenance and other needs, which has led to lower levels of property maintenance.

I also want to focus on an essential stake in this conversation. My research tends to focus on homelessness. I often find that conversations and policymaking on homelessness are siloed from housing and housing development conversations. It’s important to connect those things because we all see homelessness as a public health crisis, but not necessarily that the decisions we make related to landlord/tenant regulations can impact it.

I won’t belabor the statistics of the affordability crisis in Rhode Island because I think you had other presenters do that. But we saw recently that Providence was named the least affordable metro area. That study examined the difference between renters’ median income and the rent they are asked to pay.

Importantly, and sadly, in the past five years, homelessness in Rhode Island has doubled. In the most recent HUD (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development) count, we’ve seen that nearly 2,500 people are experiencing homelessness in the State. Around 600 of those folks are unsheltered - living outside in a place not meant for human habitation or cars. The costs of not addressing this crisis are high. We know, across decades of research, that people who experience homelessness are more likely to die, more likely to die early, have increased risk of injury, exacerbated poverty, poor educational outcomes for children, and adverse health outcomes across the lifespans. New research related to aging demonstrates the needs of elderly adults who are experiencing homelessness.

Importantly, especially for this kind of conversation, the risks to the community are also high - in terms of finances and public health. We see high economic costs associated with homeless services, emergency healthcare, hospital use, the implementation of criminal justice policies to respond to homelessness, and how working families have to come together and support one another and sometimes put their housing security at risk by letting their friends and family double up with them. It’s not just those 2,500 people who are suffering from this crisis of housing deprivation.

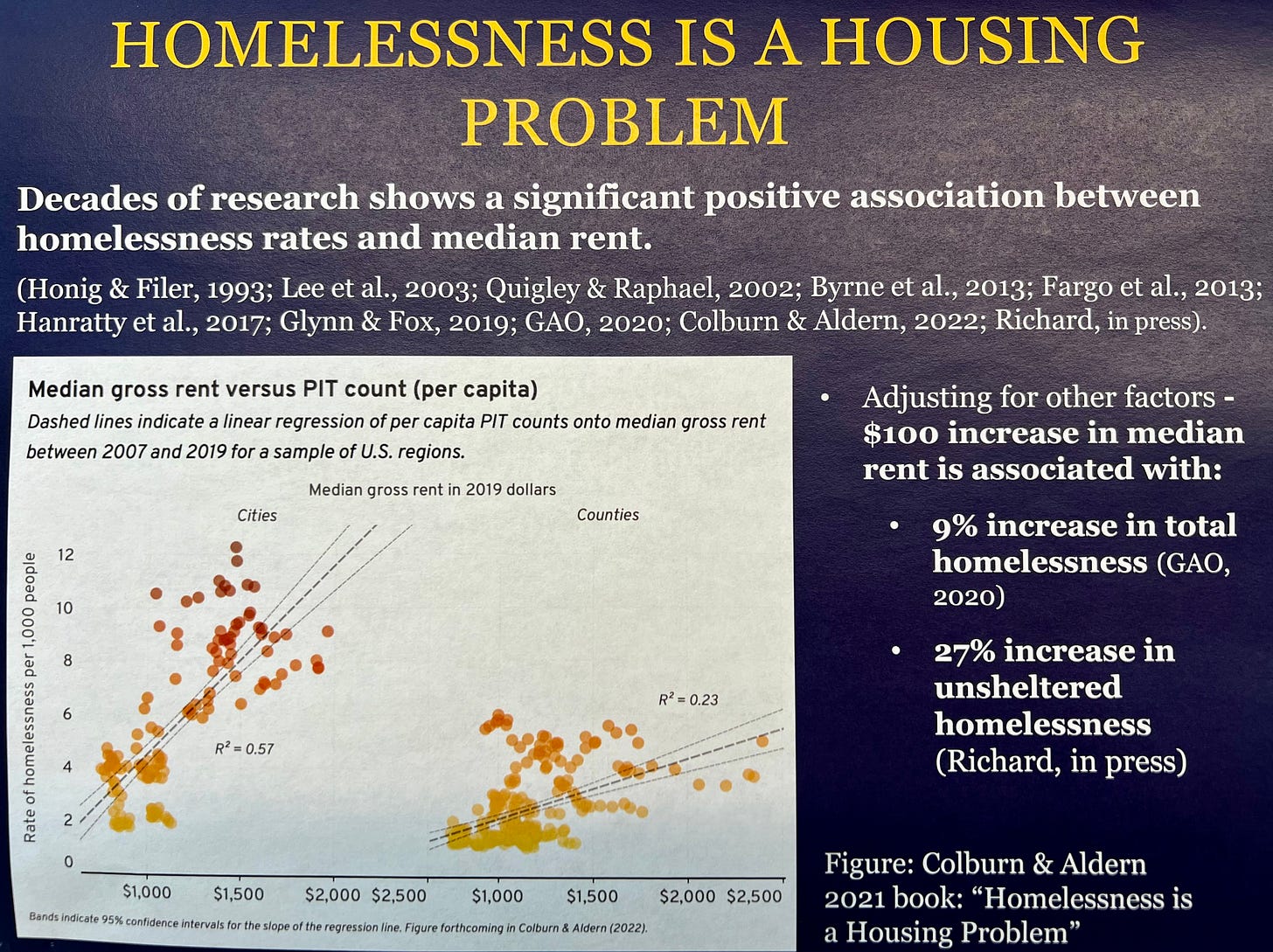

What do we do about it? Decades of research have clearly shown that the solution to homelessness is getting people into short-term and long-term housing. However, we also have an incredible amount of evidence that supports the need for housing affordability as a homelessness prevention. We have found that the articles listed here - across social science, economics, urban studies, and community development - show a strong relationship between homelessness rates and median rent.

To give you a few figures: A hundred-dollar increase in median rent is associated with a 9% increase in total homelessness. And that’s from a Government Accountability (GAO) Report. HUD requested that study. In my research looking at subpopulations, I found that the same rent increase was associated with almost a 30% increase in unsheltered homelessness between communities.

Homelessness is a housing problem. This chart, created by a professor of real estate at the University of Washington, illuminates the issue by plotting the rates of homelessness per capita against median rents.

What can we do? We are talking about producing and improving housing affordability for Rhode Island renters, but tenant protections make a big difference in a challenging budgetary environment.

Just-Cause Eviction

I don’t have the nitty-gritty of the proposed just-cause eviction policy, but I can share some of the broad strokes around what different jurisdictions and localities look like and what research has shown about the good and bad impacts. Just-cause eviction protections help renters stay in their homes by preventing arbitrary, unfair, or retaliatory eviction. That does not mean there are no evictions. It just means landlords must have a good reason to evict. Nonpayment of rent is one of those very well-used reasons, as well as any lease violation.

Dozens of municipalities operate just-cause eviction policies, tenant protections, and rent stabilization. New Jersey, Oregon, California, New Hampshire, and Washington have all passed state-level legislation. Municipalities in New York and others scattered across the country, including Philadelphia, St. Paul, and Washington DC, have also passed just-cause eviction legislation. The National Low Income Housing Coalition tenant protections database reports that, as of this month, eight states and 24 localities have just-cause prevention or good-cause eviction laws. Colorado and New York passed theirs within the last year.

What is the impact of just-cause eviction protections? Much of this research is emerging and new, but there’s a good case for it. The first recent studies have shown that just-cause eviction legislation meets its stated goals. It leads to decreased evictions and eviction filings.

This study is based on a natural experiment conducted in the State of California, where they looked at the impact of just-cause eviction in four cities and compared them to similar counties in nearby states that don’t have those policies, and controlling for other factors, to see if there was a difference in trends. They found that just-cause eviction legislation did lead to a decrease in evictions. Other research shows that these policies are associated with lower outmigration rates. In particular, that study found that just-cause eviction policies had the most significant effect on keeping low-income residents in gentrifying neighborhoods. That research was conducted in the Bay Area at UC Berkeley.

Finally, folks have done literature reviews and technical reports highlighting how these kinds of policies, through qualitative and qualitative research, demonstrate a direct and immediate impact on mitigating displacement, which can be challenging to measure. Importantly, this research looks at people’s experiences and some data.

But, there’s an argument that just-cause eviction protections discourage new housing construction. I heard that in the prior presentations, and it’s a significant concern. Don’t cite me on this, but I think the gap in needed affordable housing is 24,000 units, so we know it’s a problem, and it’s been a problem in the making for decades. It’s also a regional problem. This is an important question, but no published research supports that just-cause eviction protections lead to decreased housing construction.

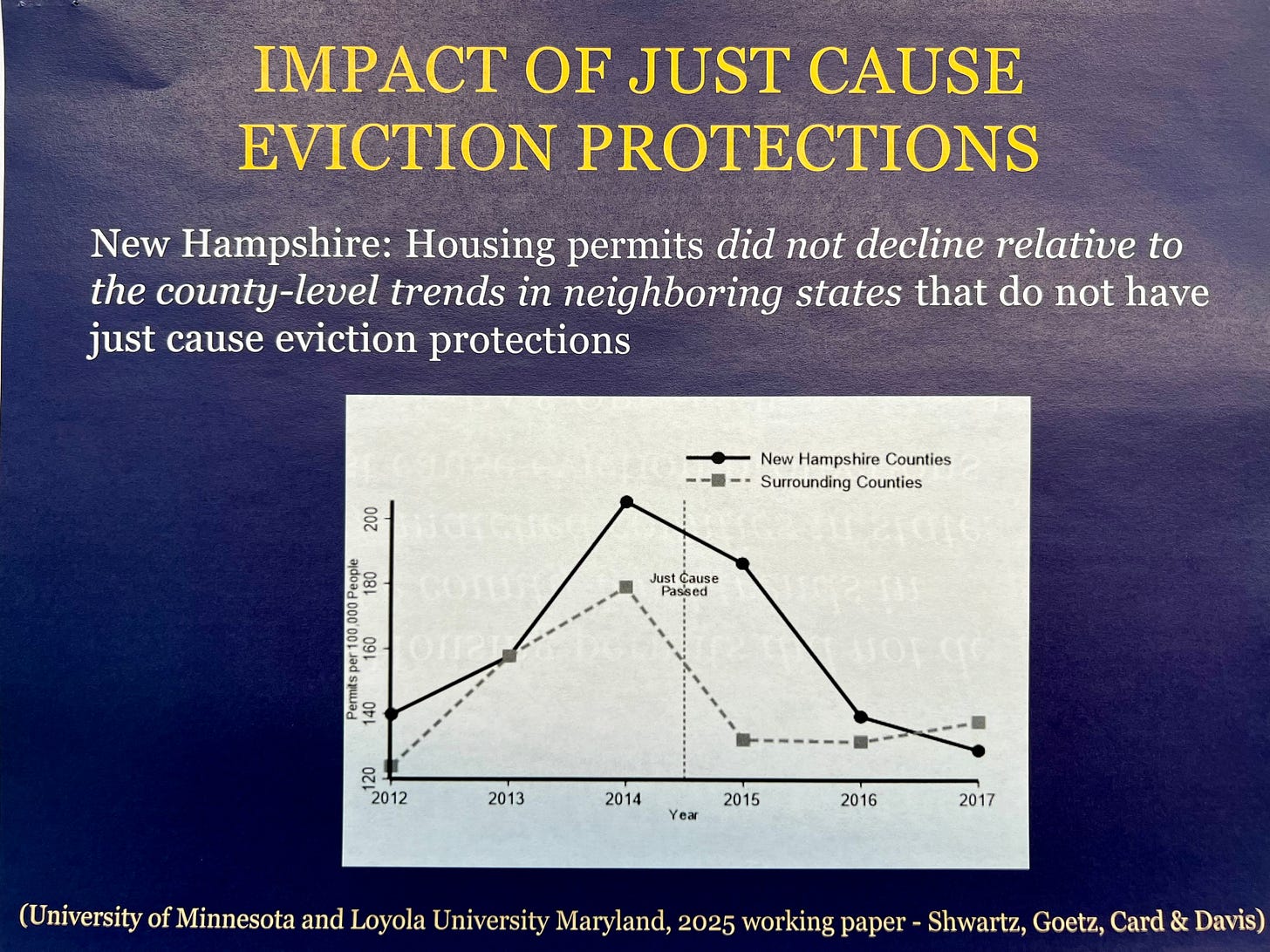

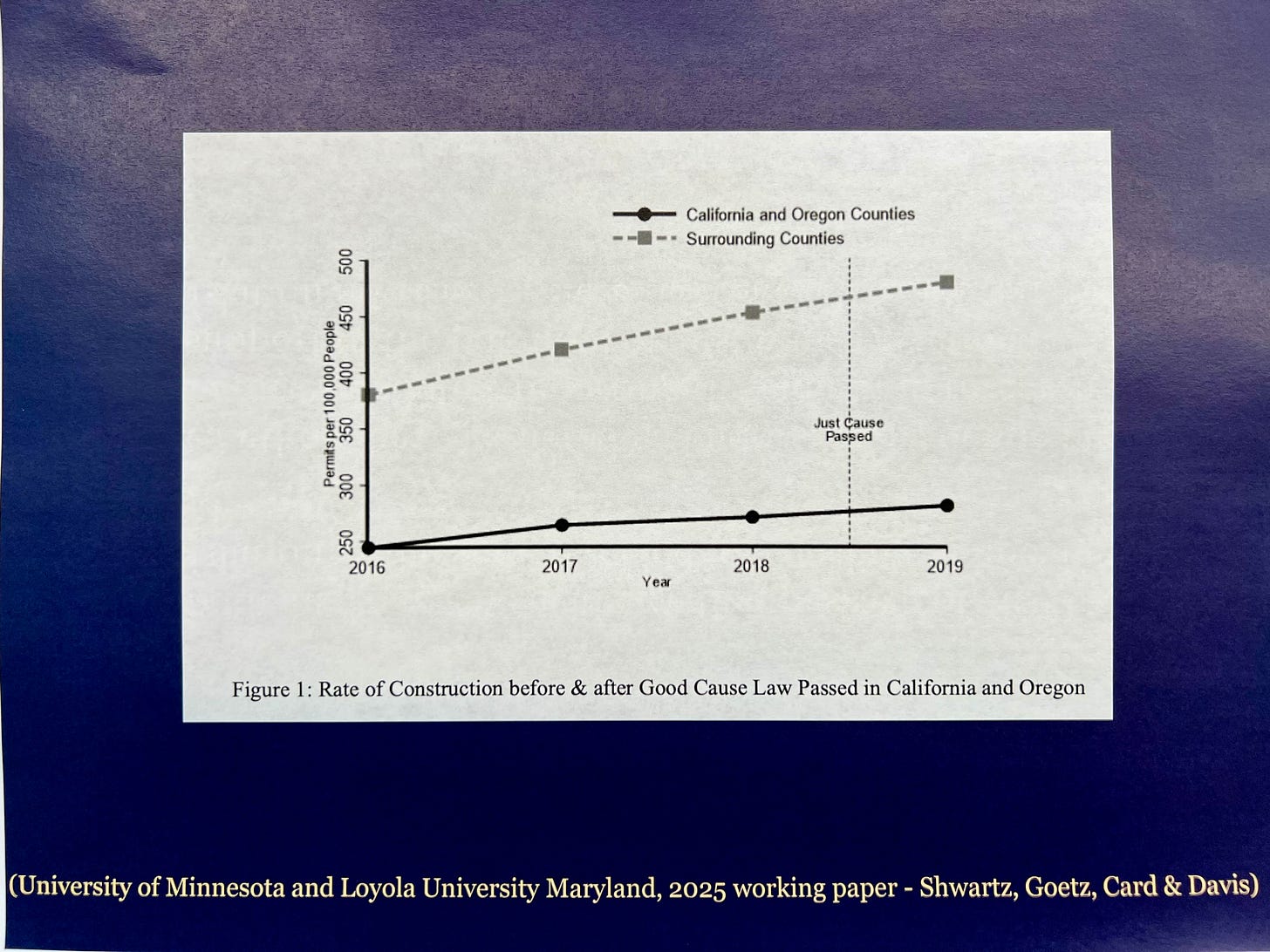

That’s the first point I want to make. To my knowledge, there’s no research on that. I would be interested to see if anyone else has that. We do have evidence to suggest that there is no significant decrease. I want to take a closer look at a working study of these policies in California, Oregon, and New Hampshire. My colleagues at the University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs and Loyola University of Maryland Department of Economics looked at pre- and post-enactment of just-cause eviction protections.

In the absence of being able to randomize cities, counties, and states to different policy landscapes, we use what’s called difference in differences models to compare similar jurisdictions with just-cause policies to those who don’t have it, just like that other study that I cited from California did, and then look at trends over time. The data used in this study was county-level data on housing production and housing permit data by HUD. It controlled for income per capita population, county-level GDP, unemployment, and housing vacancy rates.

Let’s look at some of that data. This is New Hampshire. This is plotting permits per 100,000 people, and you’re seeing that over time. Just-cause legislation was passed in the State of New Hampshire in 2015. At first, you’re saying, “Oh no, look, it’s going down.” However, the study aimed to determine whether it is going down relative to other similarly matched counties not exposed to that policy change. The authors found that housing permits did not decline relative to the county-level trends in neighboring states that do not have just-cause eviction protection. These were counties in Maine, Vermont, and Massachusetts, similar to those they observed in New Hampshire across various variables, but did not have just-cause protections.

The same thing was found in California and Oregon. Housing permits did not decline relative to the county-level trends in neighboring matched counties and states that did not have those same protections. Permitting in California and Oregon increased relative to the comparative counties. That increase was not statistically significant, but it must be noted. In California and Oregon, there have been fewer years to evaluate. Still, the trends are similar to those in New Hampshire, showing no significant difference between surrounding counties and those with just-cause eviction protections.

I know we had a lot of data there, but in both analyses, there was no evidence that the passage of just-cause eviction legislation at the state level led to a decline in housing production. This is new emerging evidence. Often, we want to ensure that the research we’re citing in these rooms has been peer-reviewed - and evaluated by others - but because these conversations are so urgent. These policymaking conversations are happening right now; the authors have shared their research with colleagues around the country and asked, “Can you endorse this? We’re still analyzing the data. Can you review it and tell me what you think?” In response, they’ve gathered 54 endorsing academic peer signatories across a wide array of public and private institutions to say this is necessary research, they got the correct data, and we should pay attention to it even though it’s not in a peer-reviewed journal yet.

In conclusion, longstanding research shows that intervening in the housing market is necessary to address housing insecurity and, at the bottom of that spectrum, homelessness. Research is emerging, but it’s potent, showing that just-cause eviction protections can produce their intended effects - reducing evictions and stabilizing households in their apartments and neighborhoods. Importantly, especially in the context of the challenges that the state is facing, they can do so without leading to reduced rates of housing production. Lastly, I want to say that given the budget limitations, many states and municipalities have to find other solutions to the housing and homelessness crisis. The passage of just-cause eviction ordinances appears relatively low-cost and effective based on what we know. It’s emerging research, but paying attention to it is essential.

When I was invited to share some research today, it wasn’t about rent control, but I know that’s part of the conversation. I can at least cite and share the findings from one recent study where economists found that rent control reduced prices by 4% and 6%, depending on the municipality and the year, but did not reduce the supply of housing units. I know that can feel counterintuitive - you might assume that would happen - but it doesn’t bear out when we look at the data. I’m happy to learn more about it and submit it to the clerk.

Eviction Attorney Steven Conti: I do a lot of evictions here in Rhode Island. All my clients are mom-and-pop businesses. Was your study based on corporate ownership?

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: I didn’t conduct the study, so I’m sharing it with some colleagues. To answer your question, no, it was about the whole realm of housing stock and housing permits. It is not specific to corporate owners. I just set the stage to say that these policies often impact corporate landlords because they’re an increasing part of the industry. I know there are exceptions built into many of these policies for smaller owner-occupied residential properties.

Steven Conti: I’m in the trenches every week, and I see the just-cause eviction protections from the opposite side, and it’s primarily negative. No landlord wants an empty apartment. Let’s start there. We want the apartments rented. Nobody throws anybody out unless there is reason, okay? Nobody evicts on a whim. That doesn’t happen because the cost to the landlord of evicting a tenant for whatever reason ranges between $5000 and $10,000 between loss of rent and repairs for every turnover. So it’s not likely that we’ll throw someone out on a whim.

The problem with just-cause eviction is you are interfering with the contractual relation between a landlord and tenant - putting conditions in. The problem is when you have a bad tenant, and the rules are you can’t disturb the neighbors, you can’t smoke - under Rhode Island law, the landlord has to prove that the tenant is in violation. Most of the time, the landlord is not living in the apartment and doesn’t see that the tenant is smoking, the tenant is blasting music at midnight, or the tenant is violent and screaming at the other tenants.

Out of all the years I’ve been doing this - 36 years - I could probably count on both my hands the times landlords were able to get other tenants to come in and testify. So when tenants are non-compliant, I recommend sending them a termination. It’s cleaner and more straightforward. Once you start with just-cause evictions, you won’t be able to throw out the lousy tenant because you will have no one to testify against them. I have 35 units myself, and the reality is that what will happen is you will lose the good tenants.

The landlord can’t deal with the bad tenants and throw the lousy tenants out because of just-cause evictions. Even without just-cause, right now, the way the system is set up, if you have a bad tenant and want to get rid of them, by the time you get into court, it takes at least three months. And then they can appeal. “I hereby claim my right of appeal.” They don’t need to post a bond. They don’t even need to pay an appeal fee. What irks me the most is when they fill out the application for In forma pauperis, they add their rent as part of their expenses, which they haven’t paid for the last three months, which now forces the landlord to lose another month’s rent and he has to pay an attorney fee again. I am totally against just-cause eviction protections because they are detrimental to the landlord’s finances and the other tenants.

I have another question. You said that just-cause leads to fewer evictions. Did you study how many good tenants move out because of the lousy tenants who stay and how much turnaround there is in the landlord’s other units? Has any study been done with that?

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: I don’t know. Not that I know of. I would happily look into it and see if any research answers that question. I don’t recall, but I will say that you are bringing up some important points that we need to research.

Steven Conti: I know it from experience, right? I’m doing it every week. I average 20 evictions a week. I see it firsthand for myself and my clients. Just-cause is a hundred percent lousy law. No matter what study you put up there, you need a reality check on what it does. You want to follow me around for a few weeks…

RI Superior Court Justice Christopher Smith: Hold on, Mr. Conti. I’m sorry, hold on. Hold on. We’re going to take things one step at a time. We have 30 minutes for each presenter to ask questions.

Steven Conti: I’ve made my point, and she answered my one question about moving out of the good tenant.

Reclaim Rhode Island’s Daniel Denvir: Is it fair to say that the real estate industry is one of the most powerful industries in the United States of America? Suppose there were findings to be found, from Philadelphia, the State of California, wherever, that it had become impossible to evict tenants because they were horrible tenants disturbing their neighbors. Is it reasonable to assume that someone would’ve funded that research and found that evidence?

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: I think so, yes.

Daniel Denvir: Thank you. Can you say a little bit about what research exists in terms of the relationship between eviction and homelessness, as well as all sorts of other social outcomes - from childhood educational attainment to health outcomes to mental health? I know there’s a lot of research, especially from The Eviction Lab at Princeton.

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: There’s a lot of research, and I can’t review it all because there is so much. We know a lot about the negative consequences of eviction, both for individuals and families, and reverberating across neighborhoods. I’ll share the findings from a research study in the Quarterly Journal of Economics: an eviction order can increase homelessness and hospital visits, reduce earnings, reduce durable goods consumption, and negatively impact credit in the first two years. What I see as one of the most rigorous studies in terms of data and statistics they use was done by the University of Notre Dame, Yale, and Harvard, where large groups of people came together to look at the best data.

The large spectrum of homelessness and housing insecurity is essential to some of my research and areas of expertise. There are folks we see outside, in shelters, and people couch surfing and doubling up, staying with family and friends. You might find studies that say that the folks in shelters or living unsheltered did not recently have a lease. Maybe they were doubled up and staying with family or friends. You could argue that eviction protections aren’t going to help them. They’re not the folks that we’re talking about. However, we have to take a more extended look at the timeframe because that person did have a lease, but before they were on the street, they stayed with friends.

Often, the eviction of your family or friend hosting you will put you on the street, but it wasn’t your lease because you were already in a cycle of negative experiences that led you there. If someone brings in research countering that, it is essential to consider those connections as not always being direct. In this study, they found that looking at it longitudinally for two years, evictions increased homelessness and then all these other costs, including hospitals and earning reductions. We found a lot of research showing a negative impact on educational outcomes in health, but I want it to be supported by the best data.

Gregory Weiss, RI Association of Realtors: Looking at multiple data sources is essential. One reason rents are going up so much is another statistic I have from the tax assessor in 2015: the average tax on a building of six units or more was $26,000 a year, and in 2023, it’s $51,000. The taxes have doubled, as has everything else. It’s not just greed. Rents are going up, but vacancies are super low, and landlords, for their own best interests, are trying to fill these vacancies. How will we help people experiencing homelessness? By creating more units. We can’t put them in units we don’t have.

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: I agree. We need to produce more units. Some of what I was sharing was to dissuade any concerns that just-cause eviction tenant protections would get in the way of that. From what we know, it won’t. I’m not here to talk about the best strategies for producing affordable housing. I know those are different conversations happening across the State. But to answer your question, we need to make more housing, which will directly impact the homelessness crisis. When it comes to immediate concerns, before those units come online, we need to do everything that we can to protect our most vulnerable residents from early death and freezing outside.

Gregory Weiss: I would point you to one study from the National Apartment Association about just-cause evictions because you mentioned you weren’t aware of any studies that showed any adverse outcomes. The University of Washington in the City of Seattle found that it’s leading to an increase in owners selling rental properties, especially mom-and-pop landlords. In your presentation, you’re saying, we’ve got these corporate landlords taking over, leading to negative issues. This study says that just-cause rental protections could encourage that to happen more quickly.

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: It’s concerning. I’m hopeful that if we pass legislation like this in Rhode Island, we could figure out how to address some of the concerns landlords have because they play an essential role. You can’t deny that protecting small landlords is necessary. I don’t think anybody wants to make it difficult or vilify anyone. We know that many folks are getting evicted, can’t afford their rent when they have to, and are trying to find another place. I don’t think the solution is not doing it but figuring out other ways to offset the concerns and costs.

RentProv Realty’s Shannon Elizabeth Weinstein: I agree with you. We don’t want anyone homeless. We want safe housing for everyone. It’s very sad. It is a national issue right now, though. Homelessness has maybe doubled across the country, not just here in Rhode Island...

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: It hasn’t doubled across the country. It has increased. We’re at the highest national record for the last two years, but not every metro area has doubled in homelessness.

Elizabeth Weinstein: Your data cited some numbers from 2012 to 2017, notably before Covid. Things got shaken up in our market, whether it was housing, people moving around, or the cost of everything. Things have changed since then. Also, during the 2012 period, we were getting out of the last downturn of our cycle, so maybe we’re in a different place right now. The cost of building is high right now, as we’re discussing developing new housing. If we were to take our housing market now and compare it with the cost of building in 2012 through 2017, things would have been cheap back then.

When it came to building maintenance, it cost less than half of what it costs to do anything now. So rent control and just-cause eviction protections are tied together - just-cause always passes with some form of rent control, so when we’re talking about those policies being a deterrent to new housing - in this market. At the same time, things are so expensive that we’re at a point different from what your data showed. I think that’s something to look into.

Also, Mr. Denvir brought up mental health issues and how homelessness can lead to mental health issues and whatnot; that’s a point that I’m interested in getting more information on because I think of it from another angle. I think it’s a what came first, the chicken or the egg kind of deal.

I know people who have struggled with mental health and addiction and have seen what it can do to a family. I understand that, and I’ve seen that with my tenants, too. Sometimes, the people who get evicted end up getting evicted because it becomes unmanageable. We see the aftermath. It’s very sad. I’m wondering if any studies go over that - the prevalence of mental health and drug addiction in the homeless population - and what we’re doing as a society to address that. When we talk about the root cause of things, we talk about supply being a root cause, but I think that’s also a root cause that’s maybe beyond the scope of what landlords can handle. I think it’s a social issue where we can’t personally be responsible for public housing with services. I don’t know if you have any studies on that or if that’s something that could be worked with. I think that’s something that we could all get on board with.

Molly Richard, Ph.D.: First, let me respond to your first question about the data used to evaluate the impact of the just-cause initiatives in the different states. I think it’s important to consider the year-to-year context. I know that the authors are continuing to add more recent data as it comes out. The study’s design is excellent because it compares counties that exist simultaneously in different states and policy contexts. Anything happening regarding the cost of materials, construction, and whatnot will impact the trends for building permits in those nearby states. Are there differences in the trends when we compare counties in states with those policies to counties that don’t?

That’s helpful for understanding and interpreting because if you’re looking at the slides, you can see that the permitting broadly is going down. Construction is going down likely because of some of the reasons you’re talking about. But we’re looking at the difference between the lines for states with just-cause eviction protections and those without.

Your other question brings up a critical point. I’m a community psychologist. I think a lot about the importance of mental health care and the needs of people who are experiencing homelessness. When you think about the root cause, what are the structural causes of homelessness? How would we study that? The data I presented came from a book, Homelessness is a Housing Problem, where they took on that question head-on.

They looked at a wide array of variables. They tried to understand why cities like Chicago have pretty low rates of homelessness compared to cities like Boston, San Francisco, and now Providence. They tested all kinds of variables, and the prevalence of substance use disorder was one of them, as was the prevalence of severe mental illness, access to healthcare, unemployment, poverty, housing prices, and vacancy rates. They found that the strongest predictor, and the only one that showed a strong relationship, was between the housing variables and homelessness rates. The question isn’t “Who in a particular community is most likely to experience homelessness?” When we ask that question, there is a strong relationship between people who have severe mental illness and those who become homeless, just like you would expect, based on their struggles with substances and the understanding that maintaining your housing requires a certain income. If you can’t get that because of a vulnerability, it will be harder for you to do that.

But there are plenty of places across the country that have a higher prevalence of those sorts of situations, adverse experiences, and health issues that don’t see the same rates of homelessness because of their different housing affordability context. That’s not to say that we don’t need increased services, mental health, and healthcare for folks who’ve experienced homelessness because it is also a traumatic experience that exacerbates these social problems that you’re talking about. Housing affordability and keeping people in their homes are forms of public health prevention, and we do not see that.

Here are all the references Dr. Richards used in her presentation:

Byrne, T., Munley, E. A., Fargo, J. D., Montgomery, A. E., & Culhane, D. P. (2013). New perspectives on community-level determinants of homelessness. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(5), 607-625

Chapple, K., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Miller, A., & Zeger, C. (2023). The role of local housing policies in preventing displacement: A literature review. Journal of Planning Literature, 38(2), 200-214..

Colburn, G., & Aldern, C. P. (2022). Homelessness is a housing problem. University of California Press.

Cuéllar, J. (2019). Effect of "just cause" eviction ordinances on eviction in four California cities. Journal of Public & International Affairs, 30, 4.

Funk, A. M., Greene, R. N., Dill, K., & Valvassori, P. (2022). The impact of homelessness on mortality of individuals living in the United States: systematic review of the literature. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 33(1), 457-477

Garcia, C., Doran, K., & Kushel, M. (2024). Homelessness and health: Factors, evidence, innovations that work, and policy recommendations: An overview of factors and policy recommendations pertaining to homelessness and health. Health Affairs, 43(2), 164-171.

Hanratty, M. (2017). Do local economic conditions affect homelessness? Impact of area housing market factors, unemployment, and poverty on community homeless rates. Housing Policy Debate, 27(4), 640-655.

Honig, M., & Filer, R. K. (1993). Causes of intercity variation in homelessness. The American Economic Review, 83(1), 248-255.

Hwang, J., Zhang, I., Jeon, J. S., Chapple, K., Greenberg, J., & Shrimali, B. 2022. "Research Brief: Who Benefits from Tenant Protections? The Effects of Rent Stabilization and Just Cause for Evictions on Residential Mobility in the Bay Area.'

Keene, D. E., & Blankenship, K. M. (2023). The Affordable Rental Housing Crisis and Population Health Equity: A Multidimensional and Multilevel Framework. Journal of Urban Health, 100(6), 1212-1223.

Lee, B. A., Price-Spratlen, I., & Kanan, J. W. (2003). Determinants of homelessness in metropolitan areas. Journal of Urban Affairs, 25(3), 335-356.

Merritt, B., & Farnworth, M. D. (2020). State Landlord-Tenant Policy and Eviction Rates in Majority-Minority Neighborhoods. Housing Policy Debate, 31(3-5), 562-581

National Low Income Housing Coalition. (Updated 2025). State and Local Tenant Protections Database. https://nlihc.org/tenant-protections

National U.S. Dept of Housing and Urban Development. (2024, Dec). HUD 2024 Continuum of Care Homeless Assistance Programs Homeless

Populations and Subpopulations. https://files.hudexchange.info/reports/published/CoC PopSubCoCRI-500-2024 RI 2024.pd

Quigley, J. M., & Raphael, S. (2002). The Economics of Homelessness: The evidence from North America. European Journal of Housing Policy, 1(3), 323-336.

Richard, M. K. (In press). Homelessness and race: The impact of structural conditions on Back, White, and Latine homelessness, Accepted for publication in Social Problems

Shwartz, J., Goetz, E., Card, K., Davis, E. (2025 working paper) University of Minnesota Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, Lovaola Universitv Maryland.

Worley, M. & Bokhari, S, Renters Need to Earn $63,680 to Afford the Typical U.S. Apartment -the Lowest Amount in 3 Years. Redfin News

Important conversation. Thanks for covering this. When smaller landlords sell to REITs and other corporations, they create risk for the entire community. Such transactions should be monitored, reported, and subject to public scrutiny before they can close. Depending on the number of units and aggregate capital, state legislators can work with lenders to craft regulations for mandatory improvements, new construction, and other concessions before allowing corporate landlords to suck the lifeblood out of our communities.

This is always a pertinent subject of interest. I would have asked Mr. Conti to define and or explain what constitutes a good or a lousy tenant.