Journalist Atossa Araxia Abrahamian uncovers the connected worlds of hidden wealth and immigrant detention

In The Hidden Globe, How Wealth Hacks the World, Araxia Abrahamian describes "how the ruling class shapes our world."

Symposium Books welcomed Atossa Araxia Abrahamian in November to talk about her new book, The Hidden Globe, How Wealth Hacks the World. Araxia Abrahamian is “a journalist whose writing has appeared in The New York Times, New York magazine, the London Review of Books, and other publications.”

The Minneapolis Star Tribune writes that The Hidden Globe is a “brilliant expose of international tax havens [that] reveals how the ruling class shapes our world… In her stellar work of literary journalism, Atossa Araxia Abrahamian peels back murky history and legalese to expose the machinations of these enclaves, how they thrive beyond the reach of laws, sovereign unto themselves… A season of unrest looms, and The Hidden Globe lays out the unvarnished truth in a luminous feat of reportage.”

Daniel Denvir, a Fellow at Brown University’s Watson Institute and host of The Dig, a podcast from Jacobin magazine, moderated the event.

The following transcription has been edited for clarity.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I grew up in Geneva, Switzerland. The book comes back to Geneva many times and begins and ends in Geneva because it’s a really weird place.

Daniel Denvir: What led you to search for The Hidden World? How did you discover that part of the world was hidden?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I grew up in it and always sensed that Geneva was a little off. First of all, I had a bunch of friends whose parents were diplomats, and they could smoke pot wherever they wanted, get parking tickets, and never get into trouble because their parents had diplomatic immunity. It was nothing crazy, but it signaled that maybe not everyone plays by the same rules. However, only after I moved away and lived in New York for some time did I start feeling like there was more to the story. When I began working as a reporter, I was writing about countries that sell their citizenship, splicing off their sovereignty and selling it to international capital in a very specific way that offended people because its citizenship means something.

I wrote a book about that, but there was something more to this story. So, I started exploring the world of special economic zones, tax-free warehouses, and tax havens. Many of these were in countries that also sold their passports, so they were familiar territory to me. I realized that the world was full of these places, and they were not hiding.

Like, in Geneva, there’s a warehouse called the Geneva Freeport, and it was just there. There were signs for it on the street. You leave the airport, and there’s a sign. You walk around town, and there’s a sign. It’s not a secret, but what’s inside is secret because it’s trillions in gold, wine, art, and all the extra stuff that rich people need to put somewhere and maybe don’t want their wives or the tax authorities to know about. The way that it works is that the warehouse is on Swiss territory, but there’s a carve-out for tax law. So it is both in Switzerland and not in Switzerland. It serves this very interesting purpose that all other places in the book also serve.

Daniel Denvir: Switzerland is famous for bank secrecy. To what degree does Switzerland play an important role in the global creation of the Hidden Globe? Was Switzerland historically a pioneer?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I’m arguing that, but I’m sure many people will say it’s actually something else. The way I see it, as a person who grew up in Switzerland, is that you get a mercenary mentality when you’re in a small country. Maybe you don’t have much going for you in the 12th century. Warring monarchs surround you, and you must do something to get by. Switzerland’s answer to this was, “Alright, we don’t have a lot of natural resources. Our people are poor and uneducated. What are we going to do? We will train soldiers and rent them to the King of France or the East India Company. That’s how we’re going to get by.”

And it works on so many levels because, first of all, all of these young men who might be wreaking havoc at home get shipped off to Indonesia or France, and they either get killed, or they’re out of the picture, which is pretty good for Swiss society. It brings home money and creates a favorable relationship with neighboring countries, so you’re less likely to get invaded. There’s no direct line between this mercenary and this banker, but I think the mentality you need to be a small country in the world, especially now, carries through. When you look at the jurisdictions I talk about in the book, there are a lot of smaller states that maybe wouldn’t have the same power as the United States, France, India, or China if you’re talking about today. [They] have their sovereignty, votes at the United Nations, and the ability to pass laws, and they’re going to use this to create structures, laws, and incentives to bring in money from abroad because they might be starting with very little.

They’re doing what they can to get by. On the one hand, it sucks because it creates incentives [for] money laundering and a lot of wealth hiding. One estimate is that $8 trillion of personal wealth, not corporate wealth, is funneled through tax havens like these. But on the other hand, you can’t blame these countries, right? What else will they do in this extremely unequal and competitive scenario?

Daniel Denvir: How would you compare what Switzerland, Cayman Islands, or Próspera under the former Honduran government is doing to something that a wealthier, more powerful country like the United Kingdom or the United States is doing? Because it seems like most countries, in various ways, are tripping over themselves to help rich people hoard as much of their wealth as possible.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Every country does this to some degree. Wyoming is a massive tax haven. There’s a lot. The United States is part of this picture. It’s just maybe not as creative as some of these other jurisdictions. It’s harder to pass laws in the United States than in Luxembourg. Luxembourg can fast-track things in a way that Canada or France can’t.

An example I talk about in the book is the chapter about outer space, the ultimate offshore. The treaties that govern outer space stipulate that no country can plant a flag and say, “This is part of Nigeria.” You can’t claim space as a country. However, the Moon and Outer Space Treaty in the sixties didn’t discuss what happened to private property in outer space. This ambiguity has given rise to countries passing commercial space laws saying, “If you’re a citizen of our country and you find some gold on the moon, it’s yours. We’re going to recognize it.” That’s important because if nobody recognizes your wealth, it doesn’t exist. Luxembourg sees this and takes it one step further with its long history of being a tax haven in mind. They decide to recognize private property in outer space for anybody. So, if you have a Luxembourg mailbox and find gold on the moon, it’s yours. Luxembourg will recognize it and go to bat for you, and they can do this much faster than any country. They do it with the help of consultants - in their case, with Deloitte. They’re very much in cahoots with asteroid mining.

This sounds insane, but it happened. For a week or so, I followed around the hereditary Grand Duke and Duchess of Luxembourg. I accidentally talked to them in an elevator. I was chatting. I was like, “Hey, what’s up?” And then the public relations person said, “You can’t do that. You can’t talk to them.”

Daniel Denvir: You can’t address them?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: No, because that’s a breach of protocol. It’s fucking nuts. But anyway, to answer your question, the United Kingdom is sponsoring a lot of tax havens offshore through their former colonies, essentially by controlling the legal systems because the appeals court is always in a United Kingdom court. However, the smaller and more under the radar the jurisdiction, the more interesting their initiatives are. They’re a pretty good window into what we will see in big countries in the future.

Daniel Denvir: Regarding the direction of travel, it seems like there’s a crisis of neoliberal globalization with attacks from the left - but unfortunately, with much more dynamism from the far right. It’s hard to imagine a free trade agreement of the nineties and aughts variety sailing through Congress again. But at the same time, the Trump administration has ultra-libertarians and economic nationalists in a contradictory, messy way. What’s the direction of travel on this? Are these places becoming embattled as people become more nationalistic? Or is the nationalism taking this ultra-libertarian Muskian form that’s congenial to this?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Nationalists love this stuff in part because it allows them to talk a big game about nationalism, but also continues free trade, continues to exploit people in factories, and does the things that they don’t want to change. England is a very good example of this. After Brexit, Rishi Sunak’s answer to our trading partners all going away was that we’re going to have free ports at all of these ports along the coast, and we’re going to have lower taxes, and maybe it’s going to be deregulated labor. It’s unclear.

As far as I can tell, this isn’t happening anymore. Rishi Sunak was very open about being inspired by the economist Paul Michael Romer. Romer made a case for Charter Cities, which inspired this weird initiative in Honduras, which we could discuss next.

But no, these guys love this stuff. The most nefarious way that nationalists use these structures is offshore refugee detention centers, which nationalists love to use because they can claim that their constitution or their laws don’t apply to these people. It’s another country.

Daniel Denvir: Like Australia. In Italy, Giorgia Maloni is trying to use Albania.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Look at any country that’s trying to get rid of migrants. They’re finding another place to put them. That involves paying the country to stop them from leaving, renting out a piece of land to set up a prison, or pushing boats back into international waters.

Daniel Denvir: That’s what the United States is doing on the Mexican border.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: And what the United States did in the nineties with Haitian migrants on Guam. This is nothing new, but I think it’s going to increase. This is the other side of the tax and the weird space law. You find spaces where you can have it both ways and not claim responsibility. Nefarious things can happen, and people will die.

Daniel Denvir: What’s the relationship that you draw out between these offshore havens for safeguarding extremely rich people’s wealth and these offshore places doing bad things to people that would be problematic to do within your territory?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: The legal logic is the same. The legal logic is this: It’s not in our country, so we can pretend it’s not happening and it’s somebody else’s problem. If Switzerland is hiding the money until there’s a political reason to get involved, like hiding money for every dictator on the planet, it’s not our problem. You’re a sovereign nation. We’re a sovereign nation. We’re going to let you do your thing. The same goes for Noro or Papua New Guinea, where the Australian prison camps were. Australia was able to say, “Not our problem. We’re going to pay you for it not to be our problem. Since our constitution is on our land only, you can’t complain to us about it somewhere else. It’s not our problem.” It’s an evasion of tax, responsibility, and morals. It’s all part of the same reasoning.

Daniel Denvir: You mentioned Charter Cities. Prospera is a pretty infamous one. This is a place that crypto bro types are attempting to carve out of the dirt in Honduras, but I think it is now being rolled up under Xiomara Castro’s government, perhaps. Where does the idea of charter cities come from, and does it have to be a tool of capitalist secessionism?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: The original idea for charter cities was just colonialism, but then, in the early 2000s, an economist named Paul Romer, who’s now won a Nobel Prize, took this up. He wrote a paper and then gave a TED Talk, saying there are a lot of countries that aren’t doing so well and have bad laws. What if we brought some good laws from other countries and set them up? Then companies would come and set up businesses, people would get jobs, and everybody would live happily ever after because there would be a better economy. That’s oversimplified, but that was the gist, and that’s how people understood it.

After years of thinking, “Wow, what a shithead,” I spoke to Romer. I read many of his papers and understood how he got there from this deeply narrow-minded economist logic. Economists are not like us. They’re really weird and think in a way I don’t think. They’re just thinking about incentives, supply and demand, and all these economic things. He got there by studying the economics of ideas for a long time and looking at how we import ideas from one country to another. It ends up being good because you have a mix of ideas, people, and things. That tends to be good for economic growth, which economists measure success by. Romer got there by thinking that law is an idea. This is a very generous read, but I am giving him the benefit of the doubt.

I changed my mind after I talked to Romer. He got to it by thinking through the economic logic. Why don’t we bring something from abroad and try to make it better? He got involved in this scheme in Honduras to carve out a piece of land, bring in foreign laws of some kind - it’s unclear whether there would be a country sponsoring these laws or a company making them up - and then see what happens. Romer dropped out fast. Things got weird and very corrupt. Long story short, this band of American libertarian tech bros hijacked the project, and obviously, there was no foreign country sponsor bringing in the laws. They were writing the charter themselves with the help of these Randian ideologues, and they found a place on this island called Groton and the Supreme Court essentially ruled that they could have it, so they had this special economic zone on steroids until recently. Honduras got a new government. They were not so into this because they’re on the left, and now the future of this place is up for grabs.

Daniel Denvir: But it also wasn’t going super. It was at the tent/hut level.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: The thing is, they have these huge plans. “We’re going to get people jobs, and we’re going to have crypto and our courts.” But - and I wasn’t able to go there - they were doing wellness retreats and crypto summits and just - bullshit. It was like a beach resort. I don’t know that nothing good was happening there, but also, nothing that bad was happening there that wasn’t already happening somewhere else. In theory, The criticisms of it are solid, but in practice, it’s a little clownish.

It’s hard to get too mad at it, but I can envision this happening more and more because countries are desperate to bring in money, and they don’t all have a government that will shoot down an initiative to bring in money. This model is going to keep getting replicated. The question is, can you do this in a way that isn’t libertarian loony land? I think you could. To go back to Paul Romer, he was saying that immigration is so messed up now it isn’t happening. Countries are not going to let more people in legally. It’s going to suck for the foreseeable future. I don’t know if you probably probably.

I think of this more as harm reduction than an actual solution. We could conceive of places like this where people can go when they have nowhere else to go. You can pitch it to a country and say it’s not your land. Don’t worry. It’s a special zone, but it’s still a place that’s safe for people who don’t have jobs not to get killed. Maybe that’s a total cop-out. Feel free to school me. But right now, I’m not saying it’s a wonderful idea. I’m saying this because it’s so bad out there, and I don’t know...

Daniel Denvir: I mean, why not? It doesn’t seem plausible to me, but why not?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: At this point, it may be more plausible than increasing immigration to the United States or the European Union.

Daniel Denvir: You’re saying that you have to recognize the incentive structures baked into the global economic order that would encourage a smaller, poorer, or less powerful country to pursue these sorts of things, so the only way to make that not happen is to change the whole thing.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Speaking of impossible solutions. The key thing here is that countries are driven to make these choices because of deep inequalities between nations and a lack of choice, so instead of a race to the top, you get a race to the bottom. Not having these massive inequalities would fix that structurally. I don’t know what else would.

Daniel Denvir: How did your writing and research of passports for sale lead to this?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Many countries now sell their citizenship to wealthy foreigners...

Daniel Denvir: Including us.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Green cards, not citizenship, but yeah. It’s An EB-5 Visa. It depends on the project, but you’re looking at a half million to a million dollars. But many countries sell their citizenship. And the pearl-clutching outrage response is often like, “Oh my God, you’re selling your sovereignty. You’re compromising your sovereignty.” And that term sovereignty, what does it mean? Why are people using this word? I found it very unhelpful and confusing. And it means whatever people want it to mean.

But it got me thinking about the other ways this is happening every day around us. To go back to these special economic zones, they’re carving out this piece of land and saying, “Same land, different rules.” What is that, if not a compromise of your sovereignty? That was the link because it’s not just passports, which is the tip of the iceberg. There are many more instances where countries are selling their capacity as a state to the market to global capital.

Daniel Denvir: There may be two different categories of things going on with free trade zones, which are supposedly about generating economic activity that will spread more broad-based economic prosperity, create jobs, and whatever. Then, there is the Freeport in Geneva, places like that, which are for rich people into jewels, wine, and artwork - as a way to move that around without paying taxes. Is how those two things emerge different?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: These things have slightly different rules in every country. A freeport and a free trade zone are fundamentally the same legal structure. It’s on a piece of land in a country and outside it. The goods in these places are considered in transit even if they haven’t been moved for dozens of years.

Daniel Denvir: Like duty-free.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Yes, duty-free in every way imaginable. It’s not just a suspension of place or an ambiguous place; it’s a suspension of time. While it may seem different to have a fancy warehouse with a Picasso versus a sweatshop, it belongs to the same type of legal regime. That’s why “freeport” and “free trade zone” are interchangeable. Quinn Slobodian just called them zones as shorthand, which is useful because even if their products are different, the logic is the same.

Thea Riofrancos: I’m curious about what is different versus what is the same about these phenomena. I’m thinking about Switzerland and Panama, for example. You’ve emphasized small countries trying to find a foothold in the world that don’t have a lot of domestic land, resources, or huge domestic markets. They think of ways to attract external revenues by making attractive financial arrangements for external investors. But Panama and Switzerland are not the same. You’re not saying that, but I’m pushing the point to ask, does it matter that much for your analysis? Does the broader place we position a country in the global economy matter? Would a country like Panama, and we could list several other countries that are more low-income, less powerful, not in Europe, et cetera. Is there more desperation in how it’s done in a country like that?

I don’t want to stereotype, but is there more corruption - meaning illicit ways to achieve the same things versus being legislated in Luxembourg? Could that be a difference? Is there a different internal social pact around it? Maybe if, on average, your median income is pretty high and your quality of life is pretty high in Switzerland, there’s more social consent around this arrangement, whereas in Panama - again, I’m stereotyping and speaking off the cuff - maybe there’s more of a precarity to this even as it’s more vicious in the way it happens because your average Panamanian does not benefit from this arrangement. They’re small countries and might do similar things, but they’re also radically different in many ways. I’m curious whether that matters or if you find it surprising that they do the same things.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I don’t think it’s the same thing. And to be clear, I believe Switzerland pioneered this in the 1200s. So it’s not the Switzerland [of today] - not that that’s anything closer to looking like Panama.

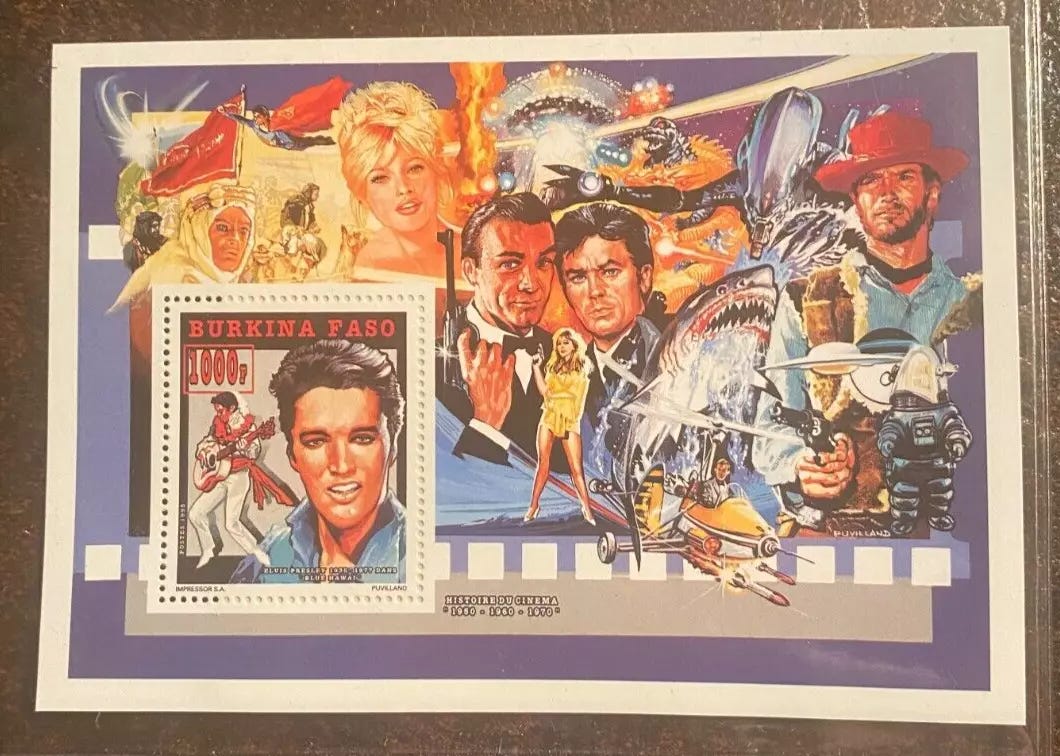

Overall, governments are corruptible almost everywhere, so that is a factor. I didn’t do that analysis, to be honest. I was reporting on what was going on. I don’t know that anyone’s gotten to the bottom of this. One interesting study found that a country that is a tax haven is more likely than another country to do something like create a novelty postage stamp for collectors. The paper doesn’t get into the causes but finds a correlation. I think it’s just the spirit of the thing. You’re like, “I can make money off the mere fact of being a state,” you keep doing it because it doesn’t cost you much. You end up with Elvis on Burkini Faso postage stamps...

Question: I’m curious if some countries in the Global South that don’t have the wealth are looking to stabilize Switzerland and hoping to achieve that. It seems that Switzerland’s place as a tax haven or a trainer of mercenaries saved it from the effects of a tumultuous European history. It looks like the borders of Switzerland have not changed significantly. They’ve remained small, but they’ve also remained incredibly stable and wealthy for many, many centuries. And I’m curious if that has anything to do with its status as a place where the wealthy go to live.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I think so. If you’re the French king and hiding gold in Geneva, you won’t invade Geneva because it’s better for the gold to be somewhere safe. It’s in your interest for it to be safe. This isn’t exactly the global south, but Dubai has established the past 50 years during t. People call it the new Switzerland, and it’s borrowed from the playbook. Initially, Switzerland was much more accommodating of laundered money - money that today would not be kosher. Money Switzerland wouldn’t be so inclined to accept today has gone to places like Dubai, which maybe would not be so stable if they weren’t set on creating stability for themselves by accepting all of this money and wealth from abroad and creating the structures for it to thrive. So yeah, I think that’s totally on point.

Daniel Denvir: An interesting difference between Dubai and Switzerland is that the United Arab Emirates are indeed invading other countries all the time, from Yemen to Sudan to Libya...

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Yes, absolutely.

Daniel Denvir: I wonder if they don’t have the patience for the long game that Switzerland’s had. They’re churning up the contradictions quickly for themselves.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: They sure are. They accelerated them.

Steve Ahlquist: I’ve been thinking about what you said about places to store immigrants that we don’t want basically and how it then becomes necessary to militarize those places or just let them fall into disorder and become virtual mobocracies or criminally run. That factors into our military spending - but there’s more to it than that. We don’t have mobocracies or militaries in the zones where rich people store their stuff. We have it in these other zones that are supposed to be similarly structured.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Instead of having a military presence to keep people away, you have a police presence - customs agents to protect the wealth. It’s a different militarization or policing. Not on the scale you would at the border where many people are crossing, but it’s still very much there. I don’t know if you have seen the movie Tenet (2020), but it all takes place in a freeport. There’s a scene where some clients are interested in the freeport, and the person who works there gives them the spiel. They’re like, “Our goal is the preservation of wealth at all costs,” implying that the level of security is so high - I’ve been to one of these places, and you have to get your eyeball scanned to get inside. It’s quite fortresslike.

Steve Ahlquist: That would be the opposite of a place where we’re forcing immigrants to live.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: It depends on who you are. If you’re an immigrant, you’re probably also getting your eyeballs scanned…

Daniel Denvir: …but to not let you out.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Exactly.

Daniel Denvir: Have you encountered political movements that challenged the capitalist secessionist politics of these zones, saying these zones are part of our polity and have not been removed from it?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: There were protests. Think about the farmer protests in India because a lot of these special zones are in India, Myanmar, and Southeast Asia. I think there are local movements that oppose the creation of these zones, especially since many involve deforestation and some pretty heavy industry, or they’re changing the landscape. People oppose them on a local level. Then there are the critics of free trade zones, which were more prominent 28 years ago, but we might get a comeback of those. There are movements, but I think it’s not on an international scale at this point. Maybe I’m missing something. I didn’t look too much into the movement side of things.

Thea Riofrancos: I was thinking about Steve’s point. It is interesting how the sweatshop type of special economic zone is an in-between level of securitization. I mean, they’re securitized, and the workers are hyper-surveilled, is my understanding. When they were first introduced in Jamaica, there were protests and strikes locally, in the same way you described.

I want to ask a methodology question. You started answering it with your anecdote about being unable to talk to the Duke and what you just said about your eyeballs being scanned. I’m curious. It’s very interesting to me. How did you research stuff that is intentionally hidden in plain sight? It’s not like we can see the map of this stuff. But you have access to it concretely, which I imagine is hard. You wrote a whole book, so I imagine you managed to get access, and I’m curious - Was it networking and relational, or did you follow the procedures to their endpoint and get legal forms of access?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I got nothing through legal procedural forms. I tried. The only place that I wanted to go to that I wasn’t able to go to was the Geneva Freeport, which is less than a mile from the place where I grew up. I emailed, I called. They’re just not interested in talking to me.

Daniel Denvir: They did not respond, period.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: It just blew me off. I talked to a guy who has a business there, but eventually, he wasn’t in town. Honestly, my primary method was spamming consultants on LinkedIn, and a surprising number of them wrote back and were game to talk. And a surprising number of them, especially in the free zone world, were like, “Yeah, this business sucks.” They were forthcoming, and I was shocked. I was pleasantly surprised that they were both critical of the world that they were in and willing to talk.

Thea Riofrancos: They were benefiting from it?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Yeah. They had an interest in telling me that the vast majority of these free zones suck because they were all pitching a better way to do it. They were consultants in this space, and they all had a better way, but at the same time, they were still down to talk shit for hours on end about how all their colleagues were terrible and the business model was terrible. It was surprising. The other thing is, because this is hidden in plain sight and many people don’t walk around asking them about it, I think it was just when you work on something for a long time, and someone takes an interest in it, you want to talk. People like to talk. And that’s just journalism.

Question: One silly comment, one question. In The Princess Diaries series, which is a YA series I loved as a teenager, the princess in the book is a Princess of a fake country that is very clearly described in the books as a wealthy tax haven. It’s not in the movies; they don’t get into that because it’s a Disney movie, but in the books, she talks about it several times because she’s a liberal kid. She talks about how it is essentially like Luxembourg.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: That’s amazing.

Question: It’s called Genovia, and it is around where Luxembourg would be. It’s a blend of Geneva and Luxembourg.

Question: Exactly. But it’s stated very clearly to be a tax haven.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Thank you. I need to read The Princess Diaries...

Question: How is this thought of by the average citizen of Switzerland? Presumably, the wealth inequality there is significantly less than in somewhere like Panama, but obviously, only some are hyper-wealthy. Are people proud to be somewhere where wealthy people stash their money?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: I think the inequality is the same, but the standard [of living] is much higher. There are insanely rich people in Switzerland. But, to your point, Switzerland is like the United States, where the cantons, like the states, make a lot of their own rules, including taxes. Geneva has gotten a lot more progressive on a lot of fronts. But each time, one Canton decides to change the law and not allow oligarchs to pay no tax and buy property. Another canton will invite them in. It’s like whack-a-mole. Public opinion can shift slightly in one place, and another will pick up the slack. Overall, I think people know what’s good for them, and there’s a certain amount of tolerance...

Question: There is a general sentiment that it trickles down?

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: Weirdly, it does because it’s a small country and quite well off. I don’t want to say trickle-down because I don’t think it’s helpful, but it is prosperous because there is just so much money sloshing around...

Daniel Denvir: Even just getting the table scraps is like a whole steak falling off the table.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: They’re competent. They know how to run things. They’re good at running things. The trains run on time. You do get something out of it.

Question: What did the freeport look like? I’m imagining a massive storage building.

Atossa Araxia Abrahamian: It looks like a mini storage but is less yellow.

Fascinating!

Love this article and how clearly it exposed and explained the cooperation between places that exploit migration and provide tax shelters for the most evil and greedy pigs!

The widespread corruption and filth held in secret by different countries really surprised me!

It also explains how we've reached the point where we're at!

IS THAT WHY THEY HATE "WOKE"??