HUD Event: How local governments are innovating to meet community housing needs Part 2

"The rate of return on the public side is the public good," said Chelsea Andrews. "That's the big difference. We're not driven by large margins."

On Thursday, March 21, 2024, HUD’s Office of Policy Development & Research(PD&R) hosted a hybrid PD&R Quarterly Update on how local governments are innovating to meet community housing needs. As the crisis of affordable housing deepens in communities across the country, local leaders are taking innovative steps to increase the supply of affordable housing. From local housing production funds to the development of social housing agencies, these leaders are at the forefront of housing solutions. At this event, we hear from local leaders about the actions underway in their communities.

In Part 2 a panel focused on the Housing Production Fund in Montgomery County, Maryland. This bond-financed fund enables the construction of mixed-income housing development, with the local housing authority retaining majority ownership and control throughout the life of the project. Moderated by Richard Monocchio, Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary, Office of Public and Indian Housing, HUD, the panel includes:

Chelsea Andrews, President and Executive Director, Housing Opportunities Commission of Montgomery County;

Zachary Marks, Senior Vice President, Real Estate, Housing Opportunities Commission of Montgomery County;

Hans Riemer, former At-large Member, Montgomery County (MD) Council; and,

Paul Williams, Founder and Executive Director, Center for Public Enterprise.

See Part 1 here and Part 3 here

Richard Monocchio: This is such a critical time for housing. How often have we seen a president talk so long at the State of the Union about housing policy?

And it was backed up in the FY 25 budget proposal. This panel is important because state and local governments have had to get more involved in this issue. We heard about some of the things that are happening and I've seen a lot of this myself as I've traveled across the country - bond issuances, set-asides, eliminating single-family zoning in some places, and relaxing land use policies. In this panel, our esteemed group from Montgomery County is going to talk about their historic program to keep the public sector dollars in the housing program so it can reinvest and build more. We know, depending on the estimate… that we are 2-4 million homes short in this country on the supply side. So with that, I'll kick it off to our panel.

Why is it so important today for the public sector to play a larger role in housing policy?

Chelsea Andrews: Every housing authority public agency across the world is trying to figure out how we can supercharge housing. A public developer is an important discussion because we’re thinking about and creating another tool, another vehicle that's not available everywhere. It's a creative model that can be duplicated in other spaces and places, and it can be used in addition to the tools that are currently available to us through HUD. That's why this discussion is important.

Zachary Marks: We know what the private sector can produce. We know what traditional tools can produce. The idea was to create this third channel. We know that housing production is cyclical. It's driven by the economy and rates. The role of the public sector is to be ready to step in for those down cycles so we don't have lost years or a lack of production that we can't recover from.

Hans Riemer: What we built in Montgomery County allows the private sector to step up and do more to achieve public goals. It allows the public sector to do more to achieve goals that have been thought of as private-sector goals. The powerful tool that we created to fund development is both affordable and allows for achieving the goal of investing in communities that have lacked investment and bringing affordable housing to affluent communities. It brings it all together and creates tremendous possibilities.

Paul Williams: Another piece of this is that a lot of the tools that exist today, the resources, are kind of one-and-done dollars. A public sector agency gets those dollars, puts them into a project, and that's it. They're spent. That's great and we produce a lot of housing that way but I think these new kinds of innovative financing tools for mixed-income public developments like what HSC has put together in Montgomery County, allow those dollars to be continually reinvested and allow for additional production. Keeping that equity on the public agency's balance sheet creates a business model, as it were, for public housing authorities to grow what their role is in shaping the market in their jurisdiction.

Richard Monocchio: As we talk about the confluence of the public and private sectors, they don't have to be mutually exclusive, right? We're talking about scarce public dollars that need to be recycled so we can create more, not at the expense of the private sector, but in addition to it.

The creation of the Housing Opportunity Commission in Montgomery County was not easy to do for a whole host of reasons. As a council member at the time, can you talk about the political realities the push and pull you faced, and how you got this done politically?

Hans Riemer: I should clarify, I was standing on the shoulders of giants. The Housing Opportunities Commission was created several decades before I had the chance to join the council. But what I built, with my colleagues here at the table, was a new funding instrument. To make that possible, we had to build momentum for housing and make housing the central issue in our community that we were grappling with at the legislative level. That required many stakeholders to believe in it - from regional governments talking about the housing shortage to council members thinking about ideas and putting ideas forward. We sought good ideas and the Housing Opportunities Commission, a strong partner to us, came forward with a brilliant, innovative idea and we worked together on the modeling. We put it into a budget and we pushed it through a council. Many council members were enthusiastic, some tried to make it as hard as possible, but that's just the nature of the process. We got it done.

Richard Monocchio: The HOC has a long and storied history in housing, and was one of the first to do inclusionary zoning which is now seen as a model for the country. What about the messaging on that? Messaging is so important for us in this industry today. How were you able to craft that message?

Hans Riemer: That's a great question. We talked about social housing, and it was interesting to see how that resonated with some audiences and didn't resonate with all audiences, but at the end of the day, the Housing Opportunities Commission showed how they could contribute to the needed production of housing to ameliorate our affordability crisis. They showed that they could be a powerful contributor to closing the shortage. That was a persuasive element of the program. And it had a very small fiscal impact. The Housing Opportunities Commission is repaying the funds established to keep the fund recycled, so the actual net impact to the county was very modest while the leverage on those dollars is just collective.

Richard Monocchio: There are some unique features to the HOC’s authority and the array of funding sources that are part of the HOC. Can you tell us what they are and how that's helped make the fund successful?

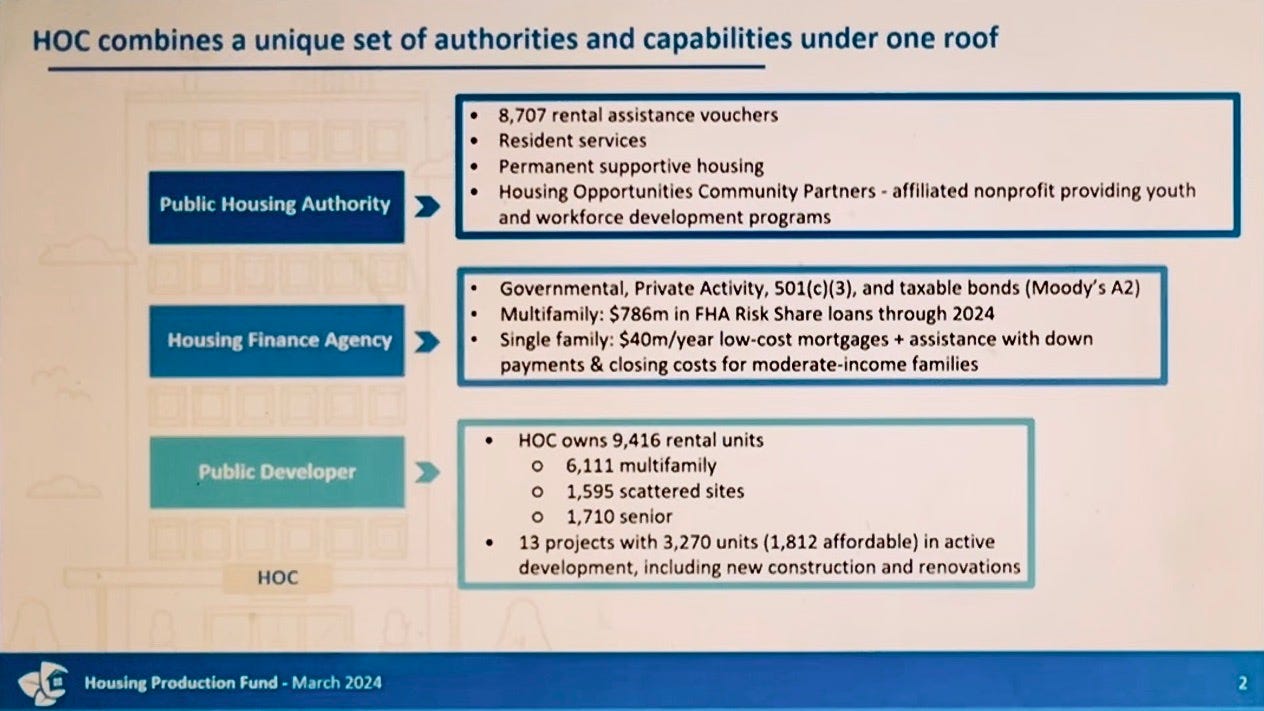

Chelsea Andrews: We have a unique scenario. We consider ourselves a unicorn because we have multiple resources under one umbrella that many other entities don't have. I will show you who we are, but before we do that, I think it's important to say to those who are viewing this that Montgomery County is right outside of Washington DC. We are a pretty large county. We have over one million residents. We are a diverse county with diverse terrain - urban, suburban, and agricultural. That's the landscape.

The HOC was created in a way that allows us to have multiple features. We are the public housing authority. We are also a housing finance agency as well as the public developer that creates the most affordable housing in our county as a housing authority.

We do not own any public housing right now. We have a lot of mixed-finance properties across the portfolio. We administer the voucher program. We have close to 9,000 vouchers that we administer. We have a full resident services program, as well as serving individuals who are experiencing housing instability, so case management services, et cetera. And we have a nonprofit arm.

We're celebrating our 50 years this year as a housing authority, but also 25 years for our nonprofit as a housing finance agency. We're fortunate to have the ability to issue bonds and in issuing bonds, we're able to finance the projects that we'll talk about today. We're also able to stand up and administer a program for first-time home buyers, mortgages, and down payment assistance. On the slides you'll see that we've issued millions and millions of dollars worth of bonds over the course of years. And then as a public developer, we are the largest affordable housing developer in Montgomery County. We have over 9,000 units, over 54 properties, variety of properties and populations that we serve, and we have a very robust pipeline.

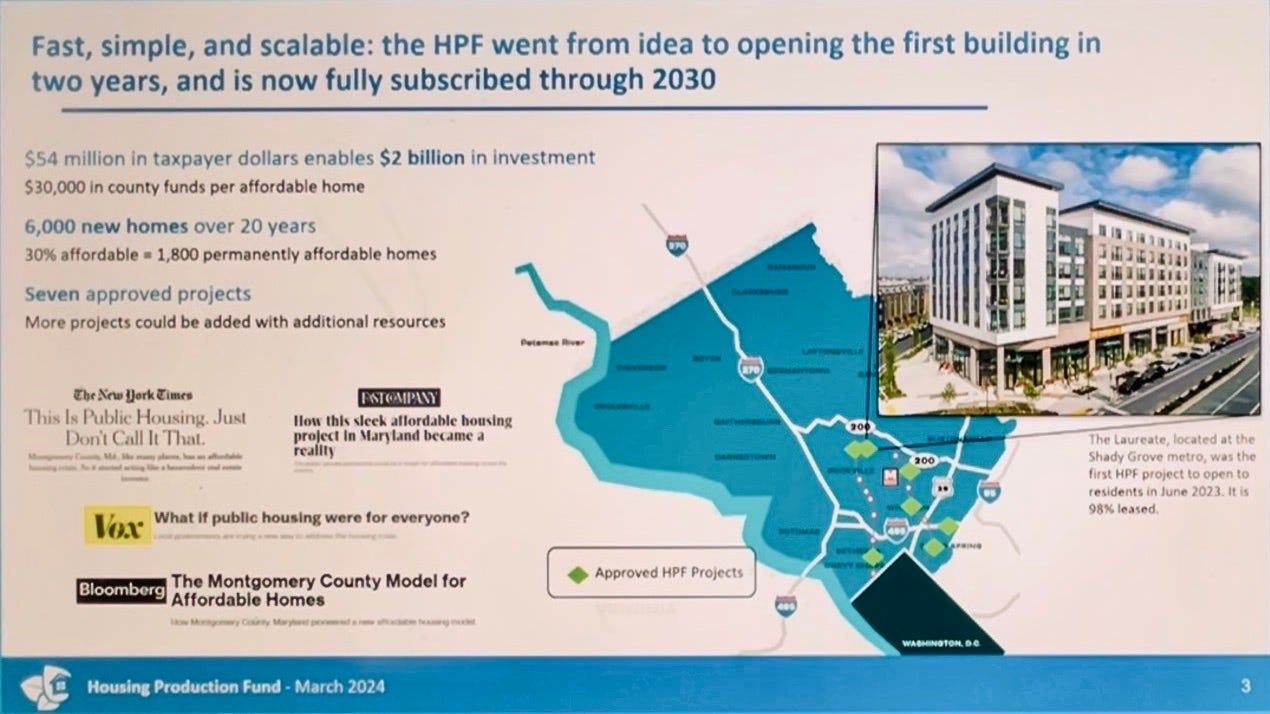

Zachary Marks: This is an example of how fast this has all happened. The housing fund was born three years ago. It's a quick period of time to then find oneself responsible for a program that has garnered so much interest and has had others take some of the ideas we've come up with and do some even more interesting things with them. You get a sense from not only the news coverage, but for us, I think the real tale is told by how many other authorities and states and localities have reached out to talk about this. It's clear that there needed to be this third channel of production.

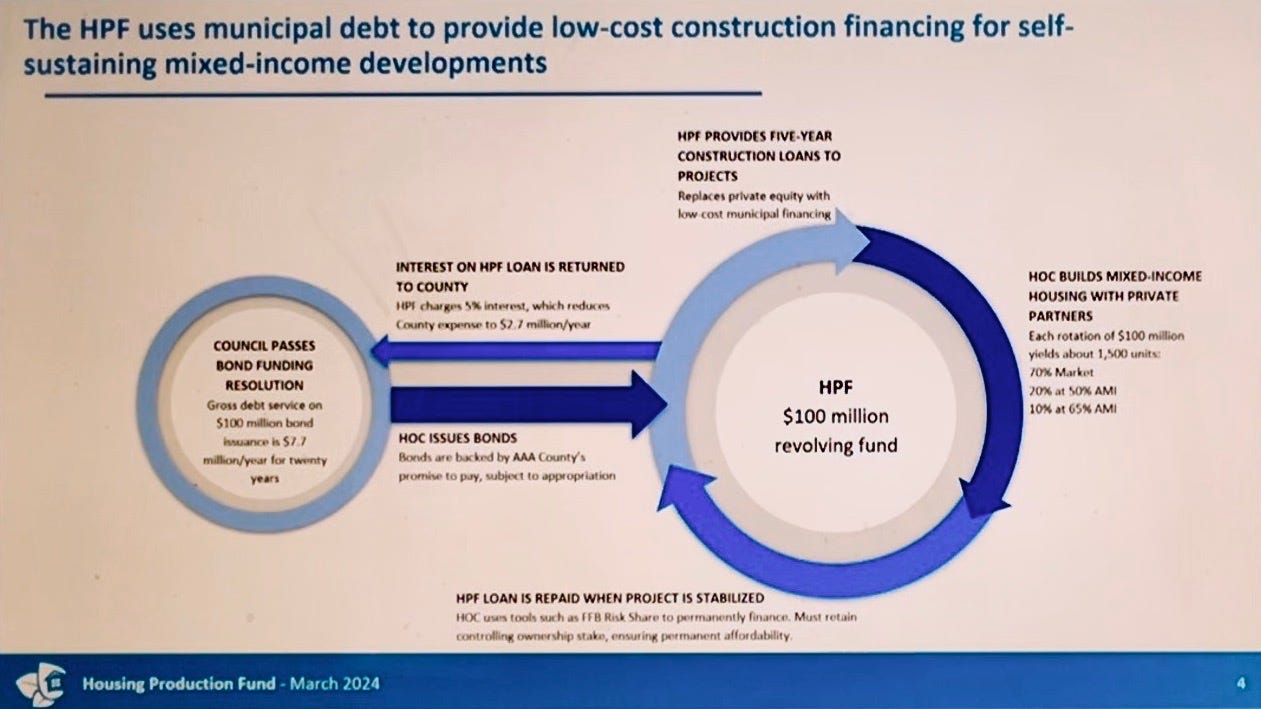

Hans and Chelsea provided good bookends for how this works. It takes two very ordinary things, and by ordinary I mean things that happen all the time. You have municipal finance on one side and you have a housing finance agency issuing long-term permanent FHA insured debt. This is stuff that's been going on since very close to the beginning. What we wanted to do was create an alternative to the use of the low-income housing tax credit, because as everybody knows, we're already doing almost everything possible with those low-income housing tax credits. The idea here to find a different equity source that is somehow providing equally good economics and with an eye toward production. The way this model works is you take the ability to access low cost municipal finance and in our case, we had a great partner in the county, which is AAA rated.

You're talking about some of the lowest cost of capital you can get. What we demonstrated was a revolving fund that could take a low cost of capital and produce a whole lot of housing for a very limited amount of actual appropriation on the county's behalf. The type may be a little tiny on the slide, but effectively, for a hundred million dollars revolving fund, the gross principle and interest on an annual basis for the 20 year bond is about $7.7 million. We charge our projects 5% annually. 5% of a hundred million is $5 million so the net cost to the county for a hundred million dollar revolving fund is $2.7 million per year, which is incredibly small relative to the size of the county budget. And this is a county that already does a metric ton in pursuit of delivering affordable housing.

The idea that we could add another substantial program without another substantial appropriation was really important, particularly since we were doing this in the midst of a pandemic. The other key piece of this is that this money only stays in for five years to get the buildings constructed, get them leased up, and stabilized. That's the stabilization point - that is where HFAs in general and HSC in particular are really good at financing stabilized, high quality assets. There's almost nobody better in this country at doing that than housing finance agencies.

As Chelsea mentioned, this is something that HOC has been doing for a long time, the ability to use the FHA risk share program to be the permanent takeout financing. It's also what gave council members like Hans confidence - he had seen HSC finance lots of stabilized properties with long-term fixed rate FHA insured debt. So when we pitched him on the fact that yes, it's definitely going to revolve every five years, we promised he didn't have to bank on the promise. It was the idea that HOC had been doing this for so long, had been producing mixed income properties, had been financing things through its housing finance agency powers, and combining it with Montgomery County's low cost municipal financing that allowed us to create this really powerful fund.

Richard Monocchio: There are a couple of things I want to pick up on. We heard some terminology here that I think is important. First of all, public developer. Some people might flinch when that's discussed, but in actuality, it's something that's growing and working. Public housing authorities, the model would've been to take the tax credits, the HOPE VI dollars, the mortgage revenue bonds, hire a developer, and that developer would realize a developer fee. It might be a land lease, and then you would go on to the next one. Hopefully you're lucky enough to get another 9% credit. But as we've heard, those are a scarce resource. Although the House passed, finally, and this has been a bipartisan effort for a long time, tax credit expansion.

Let me ask the panel. Housing deals are basically debt and equity. In terms of the debt side, a lot of projects, as we know, have stalled of late due to interest rates, but that hasn't stopped the public sector development in many cases.

Paul Williams: To the question of why so many multifamily deals are stalled - it's debt side, but also equity side. It's both pieces. Some cities are starting to address their zoning and permitting hurdles that prevent multifamily projects from happening. But at the place we are in the economic cycle, you have a lot of projects that have moved through the zoning and permitting hurdle and they're entitled and ready to go, but they're still piles of dirt. Why? Because they either can't get private equity investment or they can't get a senior loan. Tools like this give housing finance agencies or housing authorities the ability to go to those deals and say, “You know what? I have a different source of capital that's cheaper than what you're going to find on the market. If I participate in this project, I'm going to generate this amount of affordability and I'm going to put it on the public sector balance sheet.”

One of the projects that the housing production fund in Montgomery County built was essentially a deal like that. You can imagine the ability of housing finance agencies and housing authorities to have tools like this at the ready - to be able to address these issues as they come up because we have economic cycles. Whether we backstop them or allow them to drag down production or whether we lift them up and smooth them out is our choice.

Richard Monocchio: Let me shift to the equity side of the equation. Paul is right. When we're talking about return on investment and who is going to realize that return, how do you build equity? The social purpose changes the equation in terms of what gets built and how it gets built. The rate of return for government is different than the rate of return for private equity. Can you speak to that?

Chelsea Andrews: The rate of return on the public side is the public good. That's the big difference. We're not driven by large margins. We've figured out a model that allows us to leverage the market rate to subsidize our affordable housing. At the end of the day, as we continue to hold that asset, it gains equity that we then can reinvest, recapitalize, and leverage for additional development. There are so many benefits to maintaining public ownership, maintaining equity, and strengthening our financial health and capacity to do more. All of those benefits, in addition to resident services and being able to help, ensure that you don't have increased crazy rents following rent guidelines, et cetera, and allow us to have a strong impact on the outcome in the community for the long haul.

Richard Monocchio: We have a lot of folks on this call that have varying levels of experience in the development process. When you look at the HOC, how do you start? How does a project using housing production funds compare to a development that's strictly privately financed?

Hans Riemer: What I want to share was that the buildings that HOC is financing through this program are market rate units. The units that are competitive with all new housing on the market. That is an essential ingredient to our program because it allows us to finance buildings that might be in communities where there could be resistance. On the other hand, it allows us to bring in private investment to communities where there isn't enough investment. We cover both sides of that formula.

Zachary Marks: Our view is that there's not this bright line between the public and private sandbox. There are private developers, both nonprofit and for-profit in Montgomery County, that do lots of good work. It's risky to do private development. Our view is that we can help the county be a more attractive place to develop in general, which again, goes directly to supply and production, but we can also leverage that give with a take, which is that some of those projects, if you want to work with us within the confines of this fund, are going to come into public ownership and they're ultimately going to be owned and controlled by HOC. It's crucial to understand that this is designed to be an ecosystem where we are trying to afford benefits to the overall production community, in return for some important mission deliverables.

Richard Monocchio: It's important to note that yes, we're talking about housing, but in a much different context than what a lot of people think of as traditional public housing. HOPE VI began to move us away from that.

Normally the value of the asset, the benefit, would inure to the private sector. Even in a tax credit project, after the 15 year compliance period is up and the tax benefit is complete, the the asset, in the minds of many, wasn't worth nearly as much. Let's talk about the value of the asset and what that means for the future of housing production.

Paul Williams: I'll start with an example of a project that HOC has been working on. There are 100 former public housing seniors who are now in this beautiful class A building with a spa. The way HSC was able to afford to get those units in that nice new building was that they had a mixed income property that they owned nearby that they had been paying the mortgage on for 15 years, and they were able to refinance and get cash equity out of that building. That's the value of having a portfolio - you can pull [funding] out of it and do things that aren't possible when your only option is competing for more nine percents. This is another source of value for you to invest in more affordable housing. Giving PHAs and HFAs these tools to build up balance sheets is important for allowing them to be more active participants in the housing market.

Hans Riemer: When you think about a place like downtown Bethesda, it’s a super premium market. It's one of the most affluent zip codes in the country. We rezoned that downtown for significant new development. There's a lot of new development going in. HOC is also going to develop in downtown Bethesda, and they are going to leverage the value there to build and preserve units. When you have a tool like this, you can play in markets that maybe otherwise you wouldn't have access to.

Zachary Marks: The way in which American development has worked is that the city, state, municipality, or whatever provides the infrastructure and the private sector builds the market rate units and effectively capitalizes all that investment. That's great. You want to inspire people to come do business in your locality, but what we're suggesting is that we should also have a governmental apparatus that can take advantage of some of that value capture because it is future development investment dollars. It's also a way to drive policy and one of the best ways to protect tenants. Laws are great, but laws are hard to pass. Legislation is difficult. It is a lot easier to protect tenants and buildings you own. Ownership is also a great policy vehicle.

Chelsea Andrews: We're not just developing, we also have to preserve affordable housing in our communities. When you have additional equity and resources that allow you to take advantage of purchasing properties for the sole purpose of preservation and development, it allows you to ensure affordability across the spectrum. This model helps support our ability to preserve as well as produce affordable housing.

Richard Monocchio: As we move along in this country, we now realize that housing is infrastructure and it's very important to have a model like this. For the benefit of everybody who's listening and who's interested in this concept, I want to give a little example. I ran a housing authority before this position and we didn't have a balance sheet to start. What we did was be lucky enough to get a 9% deal and preserved our first building.

Lo and behold, that developer fee was like, wow, because we were the developer, I mean 1,200,000. Then we went to the next one and we wound up preserving the entire stock, but we also at the same time built our balance sheet so we can make the kinds of investments that we're talking about that HOC is able to do now.

For the folks out there who like this model and who want to start something like this, I think the panel could really be helpful to our audience with some advice.

Chelsea Andrews: This panel represents all the different pieces that you need to come together. You have to have the political will. Thanks Hans. You have to have some folks who know development and can help - either through partnership or in-house - that could help think through what this development could look like. You have to have the partner of an HFA and or entity that can issue bonds and could support the initiative. And ultimately you have to have a community.

Paul has spoken to how this has catalyzed over different jurisdictions across the United States. You have to have a community that's open and supportive of these types of initiatives. Those are the key ingredients. Then there are technical considerations. This panel doesn't afford enough time to go through many of those details, but we do have additional information on our website. And of course, hopefully in the future, HUD will also support with technical assistance and other resources to help other jurisdictions get stood up in the same way.

Zachary Marks: We're constantly thinking of different ways to present the right framework for the right audience. BIt's important that, even though we have a lot of different names for this, you do not need a whole bunch of people to start. In fact, you could probably start with just a couple because it's not the developer that we're replacing. For us at HSC, where we work with our private nonprofit and for-profit partners because they provide us with bandwidth that would require us otherwise to have a legion of people on staff - what we're really doing is replacing the private equity that Paul talked about. That doesn't need a lot of people. You need some wherewithal, you need some will, you need an analyst maybe, but in general, that is not a labor intensive part of the process to replace. If you don't want to be involved in the development process, as Hans mentioned, the first housing production fund deal was actually brought to us by the private sector, and the project was already designed and entitled. You don't have to start from scratch. You don't have to start with raw land. You can, right now, find attractive, entitled, and in some cases permitted transactions to invest in right away and take ownership and start building that balance sheet.

Hans Riemer: It's so important for elected officials to get to know their housing partners and to champion them and build the foundations able to execute when it's time. That's something I encourage everyone to do - build that partnership between the public agency, the private sector, and the elected officials to enact these kinds of reforms. That really is what this tradition grew out of.

Paul Williams: I think Zach's right. There's not a lot of activity that you really need to get started on those simpler kinds of transactions where there's an entitled project that's ready to be built in a community that can't get financing. If I had a revolving loan fund, I could deal with that quickly with a very small number of people - help you build your balance sheet, that kind of thing. There are simple ways to get started, and every jurisdiction is going to look a little bit different because every jurisdiction's institutional landscape looks different. Every state's HFA is a little bit different. They have different processes and procedures, but in all cases, there's some way to put it together because what you're doing is you're taking what's conventionally a private development model, and pull the private equity out because don't need that anymore because I have this public revolving loan fund source and you transact.

Richard Monocchio: We know that private equity is not totally replaceable because there's never going to be enough public equity. So let's talk about the interplay there.

Hans Riemer: The model we built here, even fully executed, is only a share of what we need, but it can provide a share where there might be a market shortfall. It could be that you have a piece of property in a location where the private sector hasn't responded, and now you can make that deal happen. Or it could be a place where, if you don't get in, eventually there won't be a public housing presence and now you can get in. It's probably about allowing the public sector to be on an even footing for a share of the housing resources in the community. It's important for us to remember that land reform, opening up zoning, and loosening up the market to allow for the market to deliver more affordability, is a context that affects this model. It affects everything, but this tool allows for the public good to be competitive and to continue to deliver.

Richard Monocchio: One thing that almost all public entities have is land. I have found that if you're lucky enough to own land in a sweet spot, the private sector will come. Blending this public and private equity is an interesting model because as Chelsea pointed out, the public equity is the public good. There isn't enough incentive on the private side without this public support, so you wind up getting a blended deal, but the land ownership for public housing authorities is key.

What would you folks say to somebody who said, “The government doesn't need to be more involved in this. Isn't it good enough to get some zoning change in certain districts so you can have some six flats or some multifamily housing and then let the private sector do what it does best?” What would your answer to that be?

Chelsea Andrews: My answer to that would be that more than 50% of renters are rent burdened. No matter how much you make or how much you pay for your rent, many Americans are experiencing tightness in this market that is causing a majority of renters to be rent burdened. The more we can get ahead of the curve with production, the more we could supercharge production, the better off we are. It's recognizing that that margin will get even larger if production goes down.

Hans Riemer: It's true that we can't, by ourselves, get out of the problem that we created from restrictive land use policy. It's not possible. It's too restrictive and we need significant reform in this country to allow the housing industry to produce the housing we need. We are always going to have a strong need for housing that is mission focused. What this model does is allow for the continual delivery of that in an efficient way - in a way that is easy to execute all things considered and very cost effective - but still needs to be implemented in an environment that is supportive of housing. Fortunately, they're not in conflict. A federal regime for housing in this country will support the execution. I share the premise that we can't solve the housing crisis in America strictly with public investment. We've got to let the private sector deliver the investment that it's prepared to if it has the opportunity.

Richard Monocchio: What would it take to get serious private investment into housing that's affordable for the majority of Americans? Is it even possible?

Paul Williams: The income range that HUD programs serve will always require subsidy. Construction costs will not become that low, and the rents that are affordable at those income levels aren't enough to pay a mortgage. That's why we need low-income housing tax credits and volume cap vouchers to pay for that difference. HOC has found a way to get a bunch of production at the 50 to 60, 50 to 80 AMI range without using any of those scarce congressionally appropriated subsidies. What does that mean? If you have a programmatic approach of doing this at a state level at a QAP level, that means you can have more efficient allocation of your scarce resources to your zero to 50 AMI range, which is where everybody knows those dollars should be headed.

Zachary Marks: This has to do with practicality and expediency. The reality is that we can all imagine a better world, but we've found that using the tools we have, perhaps in a modified way, making different use of municipal funding, those are the tweaks that can become a lever that can move an issue that is much larger. This is all designed to be compatible with any other solution that you want to throw at it. Supply has a big impact on the voucher program. The payment standards can go down if the cost of housing goes down. Sometimes, because there's been a little bit of a monopoly around funding affordable housing where unfortunately we've asked so much of the low-income housing tax credit, we're asking it to be the production solution. We're asking it to be the very low income solution. We're asking it to do all of these different things, even drive green building standards, and all of those things are really important. This was about showing up to help what's already going on and in no way to supplant anything else. Improved zoning? Love it. These are compatible ideas and we should do it all.

Richard Monocchio: The problem we find ourselves in as a country took many years to dig ourselves into. I want to make sure everybody understands that there isn't one solution. There are many solutions that have to work together, but the idea of public equity is so important because it can recycle, right? You don't necessarily need another appropriation. We want for future appropriations to be larger, but this can play a huge part in filling that gap - to make sure that we can finally get to a place where we have enough housing to meet the demand in this country.

One thing we haven't talked about is the people who live in the houses. We're talking about making sure people have a roof over their head, but how does this model directly impact residents in the resident service end of the equation?

Chelsea Andrews: One of the most beautiful concepts of this public model is that it allows us, as a housing authority, to make sure that our residents have an opportunity to live in beautiful, high-end inclusive building and that our community has the benefit of our resident services. That could include employment resources, education resources, family, self-sufficiency programs, or any other resource that could help support that family and children attain their greatest outcomes. That is something that needs to be thought through when we think about how we move forward in terms of funding sources to continue to support those types of resident services needs. It allows our children and our families to live in beautiful, inclusive environments that otherwise would not be available to them.

Hans Riemer: The locations where the Housing Opportunities Commission is deploying this capital is where we really need public owned housing. It's in communities that are on our transit systems - where if we don't have access to those properties they're going to be gone and it will be generations without having affordable and subsidized housing located there. In affluent communities, HOC is able to purchase and build housing. It's a very positive environment for kids to learn in. The benefits that accrue for your resident are substantial.

Richard Monocchio: The empirical data that shows that the level of schooling that a young person will achieve, the amount of money a young person will make in adulthood, the quality of life and health, are all increased when these opportunities are available. We need housing that people can afford, but why shouldn't it be for those with lower and moderate incomes? Why shouldn't they have the same access to amenities that those with greater resources have? That was more of a statement than a question. Thank you all for a robust discussion.