Experts explain the impact of policing and courts on people experiencing homelessness and facing eviction

"...every single day, I could give you an example of those rights being violated. People in positions of power who are supposed to protect and serve are not following the Homeless Bill of Rights."

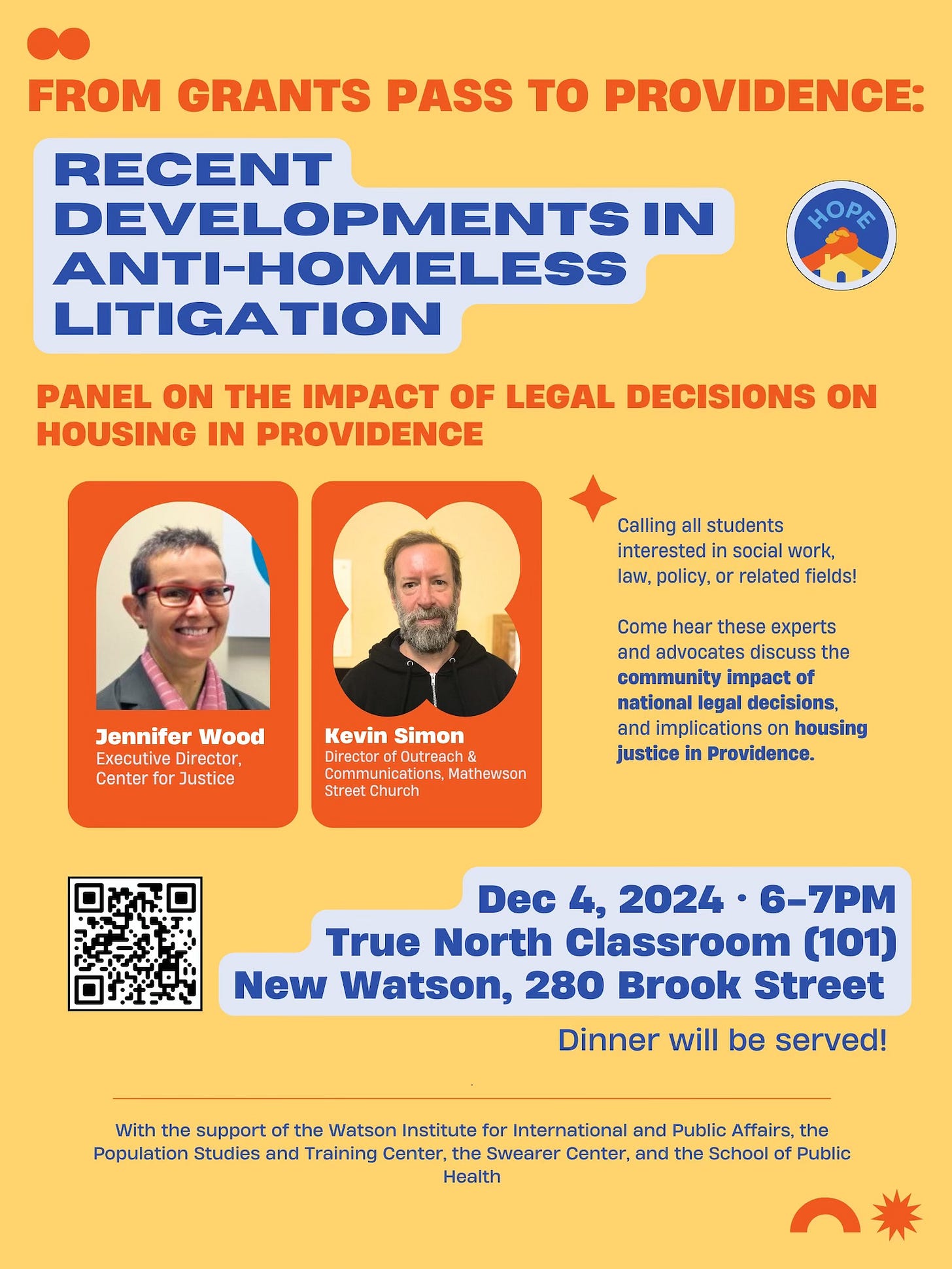

Housing Opportunities for People Everywhere (HOPE) held its second annual speaker event, which featured two guests with a deep understanding of homelessness..

Jennifer Wood is the executive director of the Rhode Island Center for Justice and has over 30 years of public interest experience in civil legal aid organizations, civil rights firms, state government, and legislative roles. Prior to joining the Center for Justice, she was the Deputy Secretary General Counsel at the Rhode Island Executive Office of Health and Human Services.

Kevin Simon is the Director of outreach and communications at Mathewson Street United Methodist Church. He’s been a part of the Mathewson community for 10 years in various roles, including serving breakfast, encouraging and managing volunteers, including many HOPE members, obtaining critically needed donations, and coordinating with multiple organizations and programs. In addition to this work, he works with State and local leaders to advocate for services and is a trusted confidant to many community members.

HOPE is a student-run organization and part of the Swearer Center for Public Service. It aims to serve the Providence and Rhode Island communities and address the structural issues surrounding homelessness and poverty. HOPE partners with House of Hope CDC, a local nonprofit dedicated to ending homelessness’s personal and social trauma, and a broader network of local advocacy organizations and direct service providers.

The event was moderated by Brown University students Calvin and Mira, co-directors of HOPE. It occurred in Brown University’s Watson Institute for International & Public Affairs building on Brook Street. The transcript has been edited for clarity:

Kevin Simon: I would be remiss if I didn’t say something to open this. I see so many familiar faces in this room. I want to say how grateful our community is for all the work you do daily to support people who need it. Please don’t stop. You’re an important voice in our community, and we are blessed and grateful for all your work.

Calvin: Jennifer, can you give us an overview of what happened in the Grants Pass case?

Jennifer Wood: I’ll try. I was looking back at it today, and it’s 80 pages long, but I will summarize. This case was decided by the United States Supreme Court last summer. It had come to the court from the Ninth Circuit from Oregon, where the Federal Court of Appeals had held that it was cruel and unusual punishment, in violation of the Eighth Amendment, to enforce certain municipal ordinances that criminalized sleeping overnight and outdoors - to strip it down to the basics.

When the Ninth Circuit made that ruling, it was a game changer for those who tried to defend people’s access to housing and protect the unhoused from being harassed, arrested, and fined. This was the first time the federal Constitution had been interpreted this way—to protect the rights of unsheltered people.

In a few minutes, I’ll describe how that Circuit Court decision was very exciting in terms of what it tried to protect, but I’ll cut to the spoiler - the Supreme Court took away the joy we experienced when that Circuit Court decision was issued. The Circuit Court is the highest level in the federal courts before you get to the Supreme Court, so it had a huge impact nationally in terms of municipalities all across the country starting to look at their ordinances in light of what had happened and say, "Oh, maybe our ordinance isn’t any good. Maybe we’re going to get sued. Maybe we should reconsider our policies here in our municipality and give this a second look." This was great, frankly. Municipalities across the country called their lawyers and asked, "Are we going to have a problem with what we currently have on the books? How can you guide us? What can we enact looking forward?"

In the last decade, there’s been an epidemic of ordinances and local-level legislation to micromanage and punish homelessness. The Ninth Circuit decision was a critical national shift that you could feel. Ultimately, the Supreme Court overruled the appeals court decision and held that the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment doesn’t apply to generally applicable municipal ordinances that prohibit the conduct of sleeping outside.

I’m saying those words very carefully because a lot of detail goes into the evaluation of municipal ordinances and what would and would not be permissible in this context. The Grants Pass ordinance did not single out a category of individuals and didn’t do draconian things. In the sense that there were fines, those fines could escalate and lead to incarceration, but incarceration was not the penalty initially imposed for violating the ordinance. When we look at Eighth Amendment analysis, the biggest thing the government can do to you is take away your liberty and lock you up, right? That’s an obvious trigger point.

The court analyzed escalating actions that the government takes to prohibit conduct and asked, "Do we think it’s cruel to fine someone?" The appeals court decision focused on the fact that the penalty itself might not seem so severe in isolation, but when what is being penalized is the fact that you have no safe place to be housed, that makes it cruel because the lack of access to safe housing was the thing that was being punished. Therefore, the punishment that was levied in that way was cruel and unusual.

There’s a whole bunch of analysis that went into the Supreme Court’s decision about the fact that the Eighth Amendment is an examination of the penalty and not the person, but that is a very fine slice of bologna when you think about how the two things come together in the context of being unhoused and the cruelty of the situation has to do with the application of escalating government supervision for someone who has no alternative.

There was also a big debate about what shelter is available and what is real. So there was a whole separate category of analysis and discussion that went into the Grants Pass decision about the fact that although there were sometimes shelter beds ostensibly available to people who were being subjected to the penalties in the ordinance, because those shelter beds may not meet their particularized needs, you can have a big legal argument about whether that’s an available alternative to sleeping outdoors.

It’s about the intersection between what is being punished, how it is being levied, and who is being regulated. Then, look at whether people have meaningful alternatives. Simply saying, "You could theoretically come to this spot and get a roof over your head, but we might not be able to include your family, or we might not be able to do that in a manner that’s consistent with your religious beliefs, or et cetera" - There’s this whole escalating set of conversations that occur about what shelter is available to that individual given their circumstances.

This analysis was the basis on which the Grants Pass case was predicated. Still, we had a challenge here in Rhode Island, trying to bring forward a constitutional theory that people had a constitutional right to sleep outdoors at the State House. I’m sure many of you are familiar with that case. It was a First Amendment case, not an Eighth Amendment case. We asserted that because it was the State House and people were protesting homelessness, it was a case of freedom of speech. There’s a commonality in both cases: government oversight, supervision, and penalties are restricted if they’re "reasonable" in terms of the manner, time, and nature of the restrictions.

It’s not a binary. It’s not whether you can restrict that behavior or you can’t restrict that behavior. You must thoroughly analyze the reasonableness of the government’s methods to control conduct. That’s on a sliding scale, against the importance of constitutional rights in both the First Amendment’s freedom of speech context and the Eighth Amendment’s cruel and unusual punishment context. As things stand today, there’s not much constitutional protection for unhoused people from being charged under municipal ordinances and removed from public spaces. The balance of power around how municipal and state officials handle encampments has been profoundly impacted by the Supreme Court’s decision this past summer.

Immediately upon the issuance of the Supreme Court’s [Grants Pass] decision, municipal leaders across the country reacted vigorously, and some were spiking the ball, saying, "This is great! We can double down and pass new ordinances that are even more restrictive and punitive." - Jennifer Wood

Mira: How do you think this decision might impact future policies surrounding homelessness and shelters, particularly in Providence?

Jennifer Wood: Immediately upon the issuance of the Supreme Court’s decision, municipal leaders across the country reacted vigorously, and some were spiking the ball, saying, "This is great! We can double down and pass new ordinances that are even more restrictive and punitive." Most of the published material is more balanced than that, saying, "Well, be aware that the Supreme Court didn’t say that we had a free pass after Grants Pass. There still has to be some attention paid to the reasonableness of the matter at the time."

But what are those limitations? Can you completely limit sleeping outdoors? Am I allowed to take a nap at noon in an outdoor place? Am I allowed to have a pillow and blanket when I do it? There are many different facets to consider in how this government regulation plays out in the public zone. It’s led to a reexamining of the attempts on the part of municipal officials across the nation to control the conduct of unhoused people, specifically as it relates to living outdoors.

Calvin: I think getting more insight into what’s happening on the ground in Providence would be helpful. Kevin, would you mind explaining a little bit about what Mathewson Street Church does? Also, how have you seen the landscape of homelessness and the need for support change over the past couple of months?

Kevin Simon: I’ve been at the church for 10 years, but for decades, Mathewson Street has just been an open door to folks in the community going through varying states of crisis. Most of the people that come through our doors are unsheltered. They’ve slept outside the night before. Many come from shelters, sleep in cars, or do couch surfing. We provide a safe space for people to have breakfast and lunch five days a week. We have a large clothing room that provides basic needs for folks. Thanks to some of the familiar faces here, we do a lot of work with the documentation folks that need to get back on the right path, like bus passes, state IDs, birth certificates, and all those things people need to take positive steps forward.

Again, kudos to so many faces here for doing that important work. The landscape has changed significantly. I wouldn’t say I know about the last couple of months, but in the last three years, I’ve seen a drastic shift in what we’re seeing for unsheltered people.

We have our friendship breakfast every morning. We’ll see 200 to 400 people enter our doors on Sunday morning for breakfast. Three years ago I knew 95% of the people coming through those doors each week, it was a place of community. It is still a community place, but that meaning has shifted tremendously. Now, I see 20 or 30 faces come through each Sunday that I’ve never seen before, and there aren’t enough hours in the day to find out where they’re coming from or what their stories are.

We all know that rising rents and evictions are contributing to folks ending up on the streets and being homeless. Jennifer and I were talking about it. She, or somebody from their organization, is in the courtroom almost every day to fight for folks who are getting evicted. All these contributing factors lead to folks not having a safe space to call home. So, the landscape? Before Covid, on a given night, probably 70 to 80 people were outside. Now that number is over 700. That paints the picture of how many folks are struggling with the disparity between living costs and wages. All these things are just leading to folks ending up on the streets.

There aren’t enough resources for so many people who want to get the help they need and deserve. We see people who are in the throes of addiction and want to get help. There aren’t enough places to get that help. We see folks with mental disabilities and physical disabilities who are looking for extra help to get back on the right path, and there are not enough resources. It’s difficult for so many across our State right now.

…one of our gentlemen who was sleeping in a tent in the center of Providence, and law enforcement came by at five in the morning and said, “If you don’t leave, we’re going to knife your tent, and you won’t have a place to stay.” - Kevin Simon

Mira: In line with that, there have been a lot of police raids on encampments. Can you talk a bit about what they are, why they happen, and how you’ve seen the frequency and use of these raids shift over the past couple of months or years?

Kevin Simon: I’m sure everybody’s read the stories, whether it’s Charles Street, Veazy Street, or some other place - there have been significant encampment raids in the last couple of years. It is incredibly traumatizing for our folks. It’s hard to describe what a raid does to somebody’s journey, and it is happening constantly. I was telling Steve [Ahlquist] earlier, just last night, and there was one of our gentlemen who was sleeping in a tent in the center of Providence, and law enforcement came by at five in the morning and said, "If you don’t leave, we’re going to knife your tent, and you won’t have a place to stay." Imagine what that does to somebody’s psyche if you’re hearing those words from somebody who’s in a position that can intimidate you and cause significant trauma. It is happening constantly, and it’s not just happening here in Providence.

I’m sure many of you have read the stories about what’s happening in Cranston and West Warwick. There are ordinances on the table that would make it what somebody said to me the other day. "They’re basically making it illegal to be alive." That’s what it feels like for so many of our folks who are unsheltered. These ordinances say you have 24 hours to remove yourself from where you are, and if you don’t, then the Department of Public Works will come through and throw all of your belongings in the trash. You need to vacate wherever you are; if you don’t, we’ll charge you with trespassing. That’s another example of how these things are implemented to grind people down. The system is constantly grinding people down without optimism or hope about getting back on the right track. We’re having a very difficult time for folks going through being outside in the State of Rhode Island.

Calvin: That’s devastating. Thank you for sharing that. It’s also a bit surprising because Rhode Island is unique in that it’s one of three states in the country that has what’s called a Homeless Bill of Rights. Can either of you talk about what that is, what it means, and how that changes how homeless people interact with the law and the legal system?

Kevin Simon: I brought it with me. I want to read two of these rights and then comment on it. One of them says. "The right to use and move freely in public spaces, including but not limited to public sidewalks, public parks, public transportation, and public buildings in the same manner as any other person." Another reads, "The right to a reasonable expectation of privacy, protected from search or seizure of your personal belongings such as a backpack or a tent to the same extent as if you were in a house."

That’s not happening. Every single day, there are blatant violations of those two things. And there are six more on here that I won’t get into, but those two specifically - every single day, I could give you an example of those rights being violated. People in positions of power who are supposed to protect and serve are not following the Homeless Bill of Rights.

Every single day, we see these things happening. For example, in front of the church a couple of weeks ago, we had 15 people on our sidewalk waiting to enter. When we opened at 8:30, law enforcement said, "You can’t be on this side of the sidewalk. You have to move to the other side." They were in a public space, in front of our church. Six hours later, the police returned and said, "You can’t be on this side. You have to be on the other side of the sidewalk." This is what’s happening. That’s the traumatizing things that are happening to folks. Imagine you’re just standing there smoking a cigarette and talking to your friends, and somebody comes by and says, "You can’t stand here," Six hours later, they come back and do the same thing. That’s not okay, and this is what’s happening. So yeah, we need to make sure that we are bringing these things to light and educating people that unsheltered people are being treated in a manner that’s just not acceptable.

Rights without an enforcement mechanism are misleading, and it makes me sad. - Jennifer Wood

Jennifer Wood: Kevin read you a couple of protected things here. One of the things I’m most distressed about is that if you read the Bill of Rights and its protections, you think that you’re living in a place where you are protected. Where you have the right to emergency medical care, vote at your polling place, confidentiality and protection from disclosure of records and information, the reasonable expectation of privacy, non-discrimination in seeking or maintaining employment due to your lack of a permanent mailing address, and equal treatment by state and municipal agencies, including but not limited to libraries, police, et cetera.

I read it when we first were contacted about the State House encampment. I thought, "Oh hell, we’re in good shape here, people." But actually, there’s no enforcement mechanism. It’s an aspirational statement of rights. It drives me crazy because people may have a card like this in their pocket and believe, even as they are being roused on a street corner, that they know their rights. Still, it doesn’t say, "and if an organization, individual, or office of government violates a provision in this statute, you as an individual have the right to sue, these are the damages you could seek, and here’s the injunctive relief you can get."

Rights without an enforcement mechanism are misleading, and it makes me sad. Although I think good people with good intentions got this legislation passed in the first place, I don’t think people thought through the implications of having no meaningful enforcement mechanism 30 years later to make the promises of the pretty words in this Bill of Rights real.

That requires legislative action. There have been a number of attempts to amend the Bill of Rights to place enforceability within it, which is necessary because we know, based on litigation, that it’s not enforceable without those provisions being added to the Bill of Rights. It’s almost a cruel joke to tell people they have rights, but they’re a way to vindicate those rights. That’s very concerning. It’s something that, perhaps, has given legislators in previous cycles a lack of urgency about addressing some of these ordinances.

Some of the ordinances that we’re seeing now are not what I would call "move-along ordinances" vis-a-vis encampments in the sense of saying, "You can’t stay in one place for 24 hours or more or sleep outside over a certain cycle," but now are "move-along and confiscation." The specific inclusion in ordinances of provisions that you forfeit your possessions by being present in a public space. That’s a new front in this war, in my view as an attorney, and I think that that’s going to create some significant issues if ordinances of that sort are passed.

Mira: Last spring, Senator Tiara Mack and Representative Cherie Cruz introduced a bill that would create the right to counsel in Rhode Island, which creates a civil right to full legal representation for individuals in an eviction case. Jennifer, from your perspective, would a policy like this slow the growth rate of homelessness, or are there other legal methods that you think would be used to prevent homelessness before it happens?

Jennifer Wood: Let me explain how the right to counsel fits into the broader framework. Almost everyone knows that if your liberty is at issue and the government may lock you up, you have a right to counsel in criminal defense. That’s the whole public defender system. I’ll say that even though the public defender system is constitutionally protected, it is underfunded and understaffed. I don’t want to give anyone the impression that even the constitutional right to counsel when you face criminal incarceration is as robust as it needs to be. I always start there because extending from criminal rights to counsel to civil rights to counsel for the most basic human rights is something we strongly support as a center and as individuals. Still, I don’t want to give anyone the impression that the criminal right to counsel works out great, so we can now build it into the civil sphere.

A study done a few years back demonstrated that the office of the Rhode Island Public Defender is about 70 lawyers short—just to meet the current needs and provide adequate representation to criminal defendants in our State. Seventy lawyers would not be big if we were in New York. In Rhode Island, it’s a very big number. So, that system is already severely underfunded, and there are areas of the law where criminal defendants do not have access to counsel.

So, with that background, there is a movement nationally and in many places in the country where certain fundamental civil rights are now becoming part of a right-to-counsel theory and dialogue. I’ll give you a couple of other examples. In Rhode Island, we have a right to counsel if someone is threatening to take your children away from you and terminate your parental rights. That is a fundamental civil right, that even though it’s not a criminal proceeding, you have a right to a publicly paid attorney if someone proposes to terminate the relationship you have with your children. That’s just one example of things that have been determined to be so basic that there should be a right to counsel in that arena, even though it’s not a criminal defense protected by the Constitution.

One of those emerging areas is the defense of housing. New York City is the origin story of the civil right to counsel for housing defense. New York City passed a statute ordinance in the context of a city that funds legal aid lawyers to represent anyone facing an eviction. They started that program and built it out over five years. They didn’t just flip a switch and magically get hundreds of legal aid lawyers available to represent the thousands of people in New York City who face eviction every year but over some time.

They first created the right to counsel, funded the right to counsel, and built out the program. The reason I mentioned those details is that it’s not "add water and stir," and you suddenly have a whole trained cadre of lawyers that can come into a state and represent people facing eviction. It’s a little more complicated than that. Still, fundamentally, the civil right to counsel for defensive housing is a policy that we need across the entire nation and is critically important to protecting one of the most basic rights people have, which is the safety of a roof over your head.

I can give the whole analysis around the downstream effects on education, health, mental health, and all of the other costs to society that housing instability and insecurity cause. Most of these civil right-to-counsel programs are not done out of the goodness of people’s hearts or because their values say that people should not be displaced from their housing without a lawyer, but for very practical reasons - which is that all these cost studies have been done that demonstrate that investing in legal defense for housing costs less than what happens when housing is lost.

It’s a very practical thing for government to invest in. It is not a universal solution for homelessness because my colleagues are at District Court every day opposing evictions, fighting for improved conditions, and seeking abatements of rent when people have not been given the benefit of a safe and habitable apartment even though they’re paying rent. When there isn’t enough affordable housing for people to live in, then even if you defend evictions, people still become displaced because they can’t afford to stay in the place where they are. Eventually, people have to move, and then they end up at Mathewson Street Church because when you look at the increase in wages over the last decade in Rhode Island and the increase in housing costs, there’s a huge gap.

Without remedying some of the underlying conditions - the economic gap between rent and income and the availability of affordable housing - you can’t solve the problem. When we first started doing private market eviction defense in 2016, decades prior, there had been no pro bono law access to a lawyer for eviction defense and private market housing - end of story - in the State of Rhode Island for decades. Legal services have always done eviction defense in public housing because when you lose public housing, you lose two things - you lose the roof over your head and a government subsidy to afford housing. Public housing is the first thing to defend on a hierarchy of needs.

However, no one was working in private market housing, and most low-income tenants in Rhode Island lived in private market housing. When we began this work, at the outset, an attorney represented 95% of landlords who filed an eviction because most people know the adage that if you represent yourself, you have a fool for a lawyer. So, most landlords are sensible enough to hire an attorney to file an eviction. Only 5% or less of tenants being evicted from their homes not in public housing would be represented by an attorney. The power imbalance was absurd. We’re very proud that we, in partnership with Rhode Island Legal Services, have clawed our way into representing many folks experiencing an eviction in District Court.

We’ve shifted that balance. It’s still 95% or more of landlords and probably 40 or 50% of tenants who counsel represents, but there’s the random intermittent reinforcement principle. Landlords don’t know which tenant will have a lawyer that day. That’s random intermittent reinforcement because many sloppy practices just bullying people out of their housing are harder to rely upon if you don’t know whether someone will show up with a lawyer when they get to court. I think it has shifted the practices of evictions in our State, and that’s a great thing. Still, we would need to have largely universal representation to level the playing field, and even then, people will be evicted because they cannot afford the rent.

Calvin: Many of us are wondering what we can do about this as students or members of community organizations. How can we respond to these changes and the homelessness crisis?

Kevin Simon: In so many ways, you’re already doing it, and we need to continue what you are doing, what we’re all doing. It is so important now to be a voice for those who don’t have one, to be present at actions that are directly affecting our folks who need change, and to be able to move forward. You need to continue to show up at the events, which so many of you are already doing. You’re coming to do work at various organizations. I know you’re all over the place, whether at our church, Amos House, contributing to food insecurity or obtaining vital documents that everybody needs. We need to continue to do these things to help folks.

But at the same time, you’re building friendship and trust with people who have been burned by the system so many times - who are promised X, Y, and Z- and none of those things ever come to fruition. By consistently showing up, people recognize they can trust and have a relationship with you. They can have faith and hope to create change, which means a lot. You may not register it, but building those relationships is the most important thing. So many of our folks are passed by all day long. Nobody says a word to them, but I watch all of you that come in, and I’ve seen you in the community, and you do the things that matter. It’s simple: building relationships, learning somebody’s story, and saying hello. You have no idea how that can change the trajectory of someone’s life. So keep doing your work, and don’t stop doing it. You’re doing so much vital work in this community. It’s needed now more than ever.

Jennifer Wood: I would echo all that and add that the terrain has shifted around advocacy for more access to affordable housing and, therefore, more solutions to homelessness in Rhode Island. I’ve practiced public interest law here for decades, and much more attention is paid to the issue of access to housing, housing affordability, and the effects of homelessness now than in pretty much the entire time I’ve been in Rhode Island. That takes thousands of people doing different kinds of work in all parts of the system. What HOPE does with street outreach, various kinds of support, and showing up at the State House is critically important.

The terms of the dialogue have shifted. This is something that you hear about in the halls of the State House. When I started doing this work, I was playing defensive ball for most of the bills that I went to testify. Some bills were harmful to tenants and low-income people. Now, that has shifted. Every year, there’s a healthy array of pro-tenant housing bills that would expand access to affordable housing but also upgrade and enforce existing laws for the quality, safety, and health of the existing housing stock, things like rental registries, and extended notice to tenants. What you are doing is part of making that shift because there’s much more attention being paid to these issues and to how the General Assembly can shift how people can access and then remain in safe, affordable housing.

Students have a lot of tools. At the Center for Justice, we’ve had some important partnerships with you to do different kinds of data, analysis, and research to back up changes that we advocate for and better serve our clients. One example? We’re intrigued about how we can get our arms around better code enforcement in Rhode Island and think about how code enforcement plays out differently in different communities. And much of this will be brute force research because you can’t just go online and get the answer. After all, all of the systems have different record-keeping systems and different public records, so we will have to go around the State with public records requests, using the Access to Public Records Act law very laboriously.

We have about ten people at the Center for Justice, and we’re mostly going to court, helping to defend people’s housing, and doing other kinds of litigation. Having folks like you help do that background work is critical to moving the policy issues because we’re very committed to changing systems and structures. Representing individuals is the most important thing we can do because if you can affect one person’s life, you’re doing something important. But I love the idea of changing the system so you can affect 10,000 people’s lives. That’s another part of what you can do, and we’ve had some good experiences working with your organization.

Kevin Simon: I want to provide one more example of this group's effect on our community, the work you’re doing, and a specific skill set that I don’t have but you do. We had asked this group a couple of months ago to locate vacant buildings across the City that could potentially be used as shelter sites, and this group followed through on that and provided a comprehensive list of buildings. You’re doing the research. It’s not always pretty, and not everybody hears about it, but that stuff matters, and it provides us with a framework to go to the Mayor and these other elected officials to say, "Here you go. It’s right here. What are you going to do about it?" So keep doing that work, too. That stuff is critically important.

Question: Is there any likelihood that Crossroads or these other shelters that mandate sobriety will change their policies so they can serve more people, given this Supreme Court ruling and the upcoming Trump Presidency?

Kevin Simon: I don’t see any shift in how the shelters are operating right now, and I don’t foresee that changing at all in the future.

Question: If there are more instances of people being policed in public spaces, is it useful to have eyes or witnesses while these incidents happen?

Kevin Simon: Absolutely. Steve [Ahlquist] and I were talking about it earlier. Any video or recordings that can be presented to the media gives us leverage to fight this fight and is critically important. Certainly, our friends tell us reality, and some of us have seen it firsthand. Still, the public and the media need recordings to say that this is happening, and we need to do something about it, that this isn’t just somebody giving you a story. This is a reality for a lot of our folks.

Question: And how about in the courts?

Jennifer Wood: A few years ago, I think I would’ve said that court watching would be a relevant protective factor here in Rhode Island, but because we’ve been able to expand our footprint in partnership with Rhode Island Legal Services, we’re in all of the courthouses in the State. Any day, there’s an eviction calendar, a legal aid lawyer in the hallway, and law students who assist us. Other student volunteers sometimes support us to assist people who show up without access to an attorney on the day of court. That’s a high-stakes gambit because what can you accomplish on the day of? Surprisingly, there’s quite a bit you can accomplish. I talked about the cultural shift of having legal aid and service lawyers in the courthouse every day when there’s an eviction calendar that makes a difference.

Question: Given how long you guys have been doing this work and the emotional or logistical difficulties, what sustains you to keep pushing through and continuing the work?

Jennifer Wood: Is this the part where you ask whether we’re tired? If so, we’re guilty as charged.

Kevin Simon: My work is a little different because I started as a volunteer at the church, and some of the most meaningful relationships I’ve had in my entire life were formed at that church. I don’t look at it like I’m showing up for work every day. I get to come and hang out with my friends. That’s how I look at it, and it’s a joy and a blessing. We’ve all been struggling to find somebody else to pick us up, and that’s what we try to do. That’s the work we do at the church and so many other organizations around the State. To answer your question, I know I look tired - I look like I’m 75 when I’m 45, but I’m blessed to be able to wake up every day and hang out with my friends.

Jennifer Wood: I’ve commented in several ways about the real progress being made. Five or six years ago, we were able to represent 75 people who were defending their evictions. Now it’s like 4,500 people. That motivates me to get out of bed in the morning. You have to be a certain person to be motivated in that way, but 25 attorneys are working in the State of Rhode Island today dedicated to housing justice, elevating conditions in the housing that our clients can afford, and elevating their dignity when they do come to court for an eviction. That wasn’t happening before, and it is happening now. That is highly motivating. It affects not just the people we represent but also all of the other people who are being confronted by the system differently because of that representation.

There’s going to be a fair amount of struggle around municipal ordinances that are looking at the criminalization of poverty. Because there are organizations like ours, the ACLU, Rhode Island Legal Services, and others, those decisions should be made with thought and care because there are folks out there willing to represent people and fight for their rights. That’s highly motivating. Those struggles are often successful, and they’re often incremental in their success. I talked earlier about how a lawyer is not a universal solution. We’re a very targeted solution to a small piece of the problem. We have to look at housing affordability and the gap between wages and the cost of living.

I did a lot of healthcare reform before I came to this job, and I learned that I don’t view healthcare as a commodity. I view it as a right. I don’t view housing as a commodity. I view it as something that people need and as a right. Suppose you’re going to make these things affordable. In that case, you typically need a subsidy for those who will never have the structural ability to earn enough money to meet the current market price. You can feel any way you want to feel about single-payer versus other solutions for access to healthcare. Still, the only way we got access to healthcare greatly expanded in this country was by expanding subsidies for those who could not otherwise afford healthcare. I see housing as very similar. I think we have to have a robust assault on getting more subsidies and more support for people who simply do not earn enough money. You can’t just wave a magic wand and afford an apartment if you don’t have the basic income support. And then, for others, it’s about the conditions and defending and having due process if you’re being displaced from your housing.

Question: We’ve met many recent United States immigrants with varying documentation statuses during outreach. Many of them expressed a double fear of being unsheltered and at risk for deportation. I was wondering about the intersection of the rights of people who are undocumented in Rhode Island and the rights of unsheltered people, especially with the President-elect’s language around mass deportation.

Kevin Simon: It’s a very scary time. In the last couple of weeks, I’ve had five or six individuals who are undocumented coming to the church and asking, "What am I going to do? I’m fearful of going back to a place where I don’t know whether I’ll survive being back in that place." They came to this country for that very reason. It’s very real for many of our folks who come through the doors. I don’t have the answer. I’m fearful of what the next month could bring for those in that situation.

Jennifer Wood: All I can say is that on November 6th, for the first time in a year or two, by 7 am, the Center for Justice received several requests for immigrant Know Your Rights information sessions and workshops. I’m asked if I can come and reassure community members about how they can keep themselves safe. It’s very real because living outdoors makes you much more likely to contact official people. And when you contact official people, you’re much more likely to come to the attention of people who may have an outstanding order of deportation or the ability to detain or deport. Being undocumented and unhoused is a dual risk and heightens the concerns of our clients who do not have a stable visa status in this country. That will require intensifying our work and your work in the coming months.

Fear is a terrible thing. It is very grinding for humans, and it causes people to be in ways that are not good for them or all of us. I don’t have much to share about that other than to say that we’ve intensified our effort to offer Know-Your-Rights information. Even without documentation, People in this country have certain constitutional rights, and we try to make people aware of that. I want to say right here, while people are listening, children without documentation in this country have an absolute right to attend public schools. This is a big surprise to most people. The United States Supreme Court decided Grants Pass, the same court decided in the seventies, that children physically present in this country, with or without legal status, can attend public schools, and public schools are not allowed to ask. It’s important for people to know that there is support for immigrants and that certain basic constitutional rights pertain to them, with or without documents. I have colleagues who are immigration law specialists who participate in letting people know how to protect themselves.

again I applaud this detailed coverage of this issue so many want to look away from.

As an underlying issue is not enough housing, perhaps there needs to be more attention to the widespread resistance from existing residents to more housing near them. The latest serious issue of this type is apparently in Johnston where the Mayor, in response to local opposition to a proposed project with some affordable housing, is trashing the state mandate for a % of affordable housing, he doesn't want anything built in Johnston except expensive single family homes (maybe a few condos)

It is understandable that residents don't want more density near them, but almost every place doing this has resulted in a housing crisis that not only adds to homelessness, it threatens our economy in man ways. But opposition to new housing is often democracy in action, not easily dealt with

Very sad!!