Daughter, Mother, Grandmother and Whore - The legacy of sex worker rights activist Gabriela Leite

"There is a third thing that I cherish. In fact, perhaps it is the thing I value most highly: freedom. Freedom to think differently, to dress differently, to behave differently..."

[Edit - November 27, 2024: Renato Martins has translated this piece into Portuguese. If you read Portuguese, find it here: Livro de Gabriela Leite ganha edição em inglês]

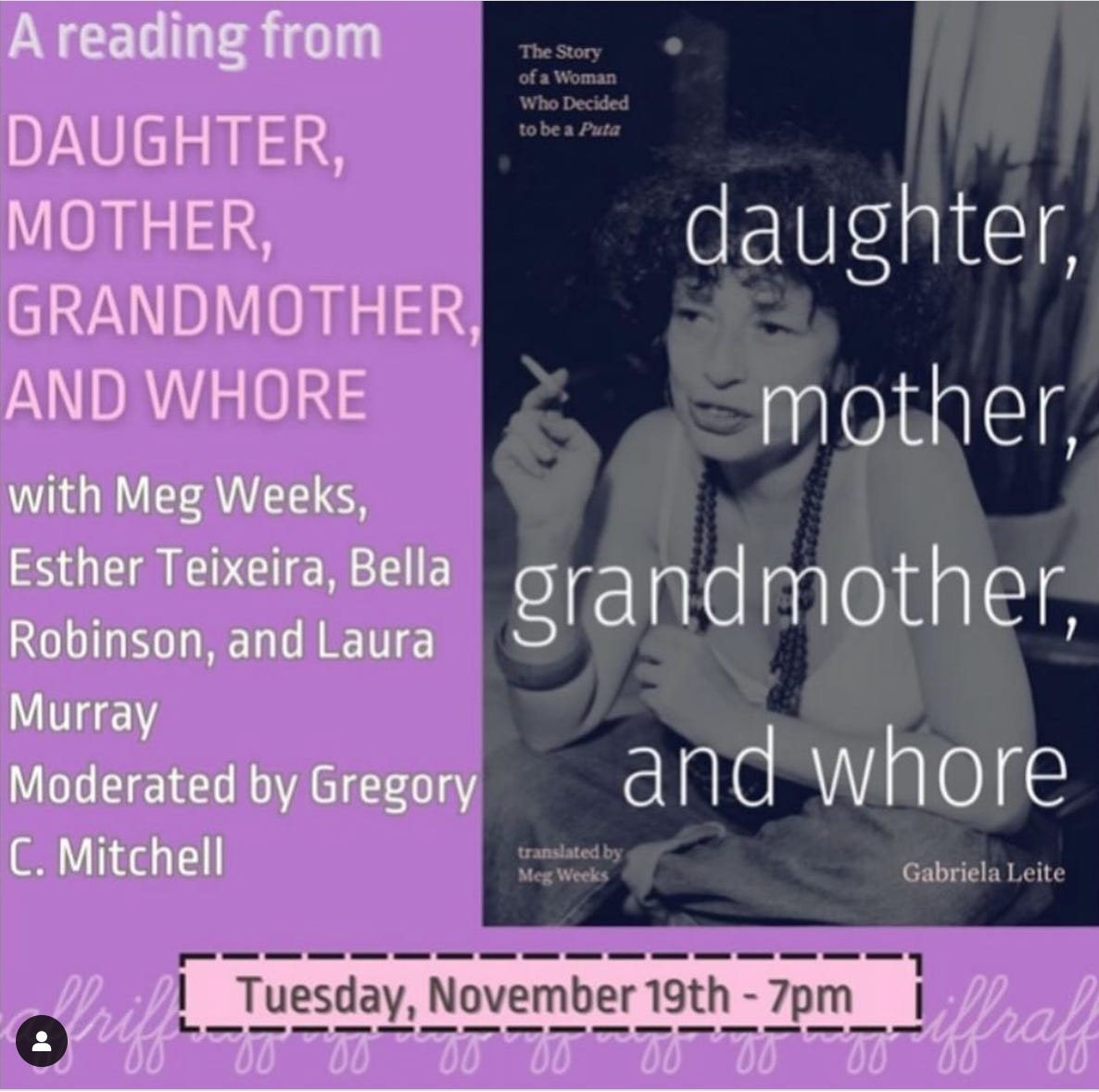

Meg Weeks is the translator of Daughter, Mother, Grandmother, and Whore by Brazilian sex worker and activist Gabriela Leite. On Wednesday, she attended a book signing at Riffraff Bookstore + Bar with her book contributors Laura Rebecca Murray and Esther Teixeira and Rhode Island’s own Bella Robinson, founder and executive director of COYOTE RI, a sex worker rights and advocacy group. The talk was moderated by Gregory Mitchell, Chair, and Dennis Meenan, ’54 Third Century Professor of Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies and Faculty Affiliate in Anthropology/Sociology at Duke University.

Weeks is an assistant professor at the Center for Latin American Studies at the University of Florida. She’s also a Portuguese translator and writes widely about art and politics in Latin America, with publications in several non-academic journals.

Esther Teixeira is an associate professor of Spanish and Hispanic studies at Texas Christian University whose work focuses on prostitution in Latin American narratives in film from the late 19th to 21st century.

Laura Murray is a professor at the Center on Public Policy and Human Rights at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and a filmmaker and advocate for sex workers’ rights who has worked alongside Gabriela Leite.

It was an eye-opening evening for someone who had never heard of Gabriela Leite and is interested in sex worker rights. The following has been edited for clarity.

Gregory Mitchell: I’d like to ask each of our panelists to share a little about how you came to know Gabriela Leite. Gabriela was involved in what she would call the prostitute rights movement in Brazil. She is globally recognized in the sex worker rights movement. Unfortunately, she passed away a few years ago. I had the good fortune of knowing Gabby, as did others on the panel, and of reading her memoir, which is the book that is now available in English.

I read that when I was doing my work in Brazil. Specifically, I was working with male sex worker’s rights, but that brought me into Laura’s circle and, in turn, Gabriela’s circle. Duke University Press invited me to read the translation, which has brought me into this wider circle. Bella and I go way back around local sex worker’s stuff. Bell, would you start?

Bella Robinson: In Rhode Island, prostitution was decriminalized from 1979 until 2009. No one knew about it until 2003 when they raided an Asian spa. The defendants hired a lawyer who explained to the judge that it was legal. It was freedom. The Craigslist Killer came to Rhode Island and robbed somebody. They called 911, and the police caught him. It’s common sense that when you criminalize someone, they can’t tell. In New Zealand, they decriminalized, but even if you have a work visa, you can’t be a stripper. So they can still harass and exploit women migrant workers.

The government claims they’re worried about saving children. We all care about children. People think they care about abortion when they don’t want to support birth control. The people closest to the problem are the people who will come up with the solution. Our research allows us to bring the voices of criminalized people to the State House, and they ignore us. We do a lot of mutual aid and think of different ways to protect our community. We recently created support groups online and a check-in culture. If someone does a check-in, they get a text - proof of life - so it’s cool.

Laura Murray: I first met Gabriela in 2004. I was an intern. I’d been working with a sex worker rights group since 2000 and then went to Brazil as an intern on an HIV prevention project that Gabriela was on the board, advising. This was when George Bush was President of the United States, and it was not suitable to be from the United States as it is today. Honestly, I don’t know if it’s ever good to be from the United States. Still, at that particular time, especially in the HIV prevention world, Bush was promoting an abstinence-only policy, which Brazil accused of being genocidal because it was known that it did not work and would lead to millions of deaths, which it did. Gabriela was especially active because of something called an anti-prostitution clause, which meant that any organization receiving funding from the United States government would have to sign a clause explicitly saying that you were against prostitution and sex trafficking.

Brazil and sex worker rights groups internationally were very vocal about how they couldn’t sign [such] a clause, so I met Gabriela in this very contentious climate. We eventually became close because I was asked to help film a documentary about the project I was working on, and Gabriela wanted to smoke. It’s essential that she’s smoking on the cover of our book. In fact, in every film experience I’ve had with Gabriela, this has become a problem because I let her smoke, so we created a good rapport and became close friends. I defended her right to smoke, but the director of the film was very unhappy with me for filming the entire interview with her smoking. Then, when I made a film about her called A Kiss for Gabriela, I spent a hundred hours with her filming, and she’s probably smoking in 70% of that. When a public television station in Brazil licensed it, they asked me if I could edit out all the smoking scenes so they could air it on public television. I was like, there will be no film!

This is all to say that she was someone I met at a very politicized time. I came to learn a great deal about politics, ways of doing politics, and how to negotiate with power in very different spheres from the states. I think this is something that sex worker activists have done brilliantly worldwide, and Gabriela was a natural leader.

To do a plug, one of the ways they were doing politics was with these T-shirts, which are from Daspu, a clothing line that means “of the putas.” I came to fall in love with Gabriela. I’m part of the organization today called Coletivo Puta Davida, and I continue to work with them.

We translated the most popular phrases to English as an homage to the book translation tour, and all of the proceeds from the sale of the shirts go to Coletivo Puta Davida, which is for Black sex workers and formed by Black sex workers.

Esther Teixeira: I’m in love with Providence. I live in Texas. I work at Texas Christian University, so being here is very special. How I came across Gabriela? My field of research is literature. I have always been interested in prostitution as a trope. I’m going to be using the word prostitution and prostitute because it is an anachronism to use the term “sex work.” After all, that term was created in the late seventies. So don’t be alarmed. I’m particularly interested in the late 19th century, and there’s a reason for that. That was when Brazil became a Republic because we were a monarchy for a long time. Also, slavery was abolished in 1888. Brazil looked in the mirror and asked what kind of nation we would like to be.

I noticed that in all the novels that deal with prostitution, there was a tendency to associate the prostitute character as a metaphor for social disease, social chaos, and unorganized urbanization. Everything terrible about urbanization was linked to prostitution. A lot of authors would use syphilis to metaphorically speak to the way that urbanization was damaging. The vice that came with urbanization was detrimental to thinking about what kind of nation we would like to be. Even going forward into late 20th-century novels, I noticed a tendency to deal with the United States’ exploitation and invasion in Central America and Spanish America. I can think of at least two novels, one of them being The Dark Bride by Laura Restrepo, a famous Columbia writer who talks about the Rockefeller family in Colombia exploring for oil and using prostitution to talk about what the United States was doing to the earth.

It’s not hard to think about how we think about what kind of nation or society we want to be in moments of crisis. We get obsessed with family values - we see that happening now, the way politics is going backward here. I just read an article today about how the Republican Party went from pro-life to pro-family because they want to bring back family values in America. As a bridge to what I saw in Brazil in the late 19th century, it seems like we’re going back to putting the family in the center of national interest, and Gabriela was, to me, a counter-voice to this image of the prostitute that I noticed in both literature and film.

It struck me to see her on national TV for the first time, with her face right there. She wasn’t covering her face or her voice. She wasn’t mortified, and she explained who she was. That was a paradigmatic change for me as a reader and a curious person. It changed the course of how I saw things. I incorporated her memoir into my literary scholarship to demonstrate how she was an author. Because who is an author? Who has the privilege of being called an author? I tried to bring her and other sex workers who are also authors to the literary canon, the Brazilian literary canon, of course.

Meg Weeks: So I first discovered Gabriela in the fall of 2016. I just started a history PhD and entered the program with a completely different project. Studying sex work had never crossed my mind. Still, in some preliminary archival research, I came across a document from the dictatorship period in Brazil, which was from 1964 - 1985, when the political police identified prostitutes as a potential source of subversion, which I found fascinating. Why would it be that sex workers were considered not an eyesore or a necessary evil, which I knew from my studies of previous periods, but they were considered politically subversive - like there was something in their discourse or ability to organize that would threaten the social and political order of the State. That struck me as fascinating and led me down this research rabbit hole.

In that research, I came across Gabriela as one of the founders of Brazil’s sex worker rights movement, and I read both her memoirs. She wrote two memoirs, one that was published in 1992 and one that was published in 2008. The second one is the one I’ve translated. But I read both her books and anything else I could get my hands on that she had written or that was written about her. I watched the film that Laura made, a short documentary, A Kiss for Gabriela, and thought, I must meet this filmmaker. I knew that Gabriela had passed away. I never met her myself. I got in touch with Laura, and we met in 2017 and got to be friends and colleague scholars. A friend of mine, Sarah Freeman, encouraged me to take on this translation project. I described the book to her, and she said, “You should translate this book. It sounds fascinating.” And I was like, “No, I can’t do that. I’m not a translator. That’s not for me.” She said, “No, you should try it, and I bet you can do it.”

So I started doing it. It was a long process. It took several years, and eventually, we found a publisher. Esther and Laura, but especially Esther, did a lot of leg work getting the intellectual property rights. That wasn’t very easy, legally speaking. I’m grateful to Laura for putting me in touch with Esther, who also managed a Spanish translation of the book, which hopefully will come out soon. And then the three of us birthed this project together.

I’m the translator but don’t feel ownership over this book. We did this together, envisioned it together, and took care of different aspects of its production. I’m so glad we’re doing this book tour together because the book resulted from a collaboration that had its conflictual moments but was beautiful. One of the things I’m proudest of in my career so far is not just having done this but working with you two. It’s our last event, and I’m a little emotional. I’m probably also exhausted. I’m grateful to you two.

Gregory Mitchell: I want to start by hearing from you about how you came to know this work, but I think it’s time we share it with them. We’re going to read two passages.

Meg Weeks: I will start at the beginning and read the first section to give you a sense of Gabriela’s philosophy and worldview.

The Greatest Lesson

“I love men. I love being around them, and I have never met an ugly one. They are all handsome, each one with his own characteristic smell, his walk, his gaze. They harbor an immense love for their mothers and for their own bodies. Fat or thin, they all have beautiful bodies, even when they have little pot-bellies. Sometimes I ask myself how they manage to walk: Does the dick in between their legs get in the way? I haven't worked up the courage to ask this question, at least not yet.

“Another thing I love is saying what I think, with no filter. Those who read this book will immediately notice this about me. I have learned a thing or two in my time on earth. One of them is the importance of having an opinion, of speaking up when you don't like something. It took me a while to acquire this right, and, for that reason, I will never give it up. I spent a good part of my life fighting for it, and now I am spending another part trying to convince my prostitute colleagues that it belongs to them as well.

“There is a third thing that I cherish. In fact, perhaps it is the thing I value most highly: freedom. Freedom to think differently, to dress differently, to behave differently. I don't know where my passion for freedom came from exactly — my life is full of many certainties, as well as infinite doubts and contradictions —but it is here to stay.

“My destiny up until this point was guided by these three loves. And, as we all know, love doesn't only bring happiness. It causes a great deal of pain as well, in ourselves and in those who are close to us. I know that, because of my obsession with breaking chains —be they political, cultural, moral, or psychological —I have hurt some people who are dear to me.

“But I believe that I have also helped countless prostitutes to lead more dignified lives. I was, am, and will continue to be responsible for my actions. What one thinks of them depends on one's outlook on life. As long as I can still exercise my freedom, I have nothing to worry about.

“This is the greatest lesson I have learned. I, daughter, mother, grand-mother, and whore.”

This is at the bottom of page 143:

The Controversy Surrounding the Word Returns

“There have always been people who say that I don't fit the profile of the Brazilian prostitute. People from the Workers' Party always compared me to Eurídice Coelho, an activist who is poor and Black and has little formal education. That was difficult for me. They insisted on denying who I was.

“At the end of 1988, we decided to launch a newspaper, called Beijo da rua, or Riss from the Street, in Recife, where we were hosting the First Meeting of Prostitutes of the North and Northeast. We even had support from the city's mayor, Jarbas Vasconcelos, who allowed us to put on the event in a theater.

“The first issue of Beijo da rua, which was a big hit, included a poem by Carlos Drummond de Andrade called ‘A puta’ (‘The Whore’). At the launch party, I was standing around drinking beer when all of a sudden, a prostitute appeared, furious, wielding a knife. She shouted, ‘I want to know who at this bullshit of a newspaper is calling me a puta!’? With difficulty, the owners of the bar were finally able to remove the knife from her hands. I explained that Carlos Drummond de Andrade was a poet from Minas Gerais, that the word puta wasn't a curse but, rather, a compliment. She still wanted to kill me. I told her, ‘This newspaper belongs to us!’ She only responded by insisting that she wasn't a whore! Unknowingly, I had run the risk of having my throat slit right there at the newspaper's launch party. The woman must have suffered a lot from being called a whore, like all of us had, no doubt. But for her, it seemed to be a particularly acute trauma. Eventually, she came around and understood our intentions, and everything turned out fine.

“At the Third National Meeting in 1994, a number of issues came to the fore, like sexual fantasies, 80 The debate over terminology reappeared as well. The Third National Meeting of Prostitutes, we had originally wanted to call it. But, by that time, no one wanted to use the word prostitute anymore. Apparently, now that we were organized, we needed a more "serious" term. Fernando Gabeira, a politician from the Workers' Party, proposed the term profission-ais do sexo, or sex professionals. The Brazilian Network of Prostitutes came to be known as the Brazilian Network of Sex Professionals, and thus everyone started calling prostitutes sex professionals. For what it's worth, I'm against this. I believe that it is important to take ownership of the terms prostitute and puta, rather than shy away from them.

“At a meeting in Florianópolis, in southern Brazil, Roberto Chateaubriand, one of our allies, organized a panel to discuss the history of the word prostitute. I was also summoned to speak about it at the Faculty of Linguistics at the University of Campinas. They were thrilled with my presentation. It is certainly a juicy topic. Our colleagues elsewhere in Latin America consider us behind the times in relation to them, because they use the term sex worker, and we still haven't overcome the stigma by continuing to call ourselves prostitutes. 81 But I think they've got it all wrong; it seems to me that changing the term is more like an apology than an affirmation.

“At a Latin American conference on AIDS in Buenos Aires in the mid-2000s, the organizers distributed a pamphlet with instructions for volunteers. A section titled ‘Words That Under No Circumstances Can Be Used at This Conference’ listed ‘prostitute.’ My panel was one of the best attended, as we had just launched our clothing line, Daspu, and everyone wanted to know who we were. There we were, surrounded by all the do-gooders of the UN and other organizations and institutions. The chair of the panel, the leader of an Ecuadorian prostitutes' organization, asked me: ‘How should I introduce you, Gabriela?" And I responded, "Say that I am from the national organizing committee of the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes," knowing full well what would happen. I was the third person to speak. The chair introduced me in Spanish: ‘I have the great honor of introducing to you all Gabriela Leite, one of our most senior leaders, who is a member of the organizing committee of the Brazilian Network of Sex Workers.’ When I took the microphone, I said: ‘I am very happy to be here, but I must correct my colleague from Ecuador. I would like to say that the name of our organization is the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes, and we would like it to be called that, so each time you refer to us, please call us the Brazilian Network of Prostitutes. We like to be called prostitutes.’ I repeated this, over and over again. I got pissed off as only a puta can.”

Gregory Mitchell: One of the interesting things about this translation is that it has an introduction by Carol Leigh, who, in addition to being a sex worker and a global leader, especially in the United States, California, and the Bay Area, was also a performance artist who performed as the Scarlet Harlot and coined the term ‘sex worker’ in 1979. Unfortunately, the introduction to the book was the last thing that Carol wrote before she passed away. It’s interesting to hold these terms in tension and think about the deliberate act of translation, right? This is an event about translation and what these words mean in different cultural contexts and time periods.

Meg Weeks: Terminology generated a lot of discussion among the three of us. It was an issue that was very dear to Gabriela’s heart, as expressed in the passage just read. She was skeptical of the move to embrace sex worker as a term because she felt that it sanitized the movement of its more deviant elements that she thought were the kind of source of its power and foundational ethos. Instead of mainstreaming prostitutes’ rights, [she saw] a unique ability to critique the mainstream if they stayed on the margins of society rather than embracing what we might call respectability politics by foregrounding the labor aspect of what they did, which for many activists was very important.

We had many conversations with Carol Leigh while working on moving forward with this book. She coined the term ‘sex work’ in 1979 because it was very obvious to all of her colleagues that what they did was work. So, on the one hand, it was a straightforward, obvious move to call it sex work and highlight the fact that they were laborers. But she also said it was a joke when she first came up with the term. At first, it was the ‘sex use industry’ - pushing back on women being objects to be used. But in her Scarlet Harlot one-woman show, when she introduced the term, her character’s mother said, “What? Do you work in a dildo factory?” While highlighting the labor aspects of the movement, she was interested in maintaining a sense of humor about it and not becoming too self-serious.

The term took off and is in our common parlance about selling sex and sexual commerce today. But she and Gabriela maintained skepticism about what it took away from the movement to mainstream it. We wanted to ensure skepticism was present in the book and the translation. I used my discretion to intuit when I would translate the word, leaving it in italics or Portuguese as “put” rather than using “whore.” The main title of the book is a direct translation from Portuguese. We tweaked the subtitle a bit because we had some differences of opinion, whether to keep the word “Puta” in the title in Portuguese as a gesture towards a certain kind of Latin American puta feminism, of which Gabriela is one figure in a larger movement.

But I felt strongly about bringing the full title into English because of the provocation that it was originally written with in mind - that someone reading this book title would be shocked. I wanted people to have that experience in English. The subtitle in English is "The Story of a Woman Who Decided to be a Puta." In Portuguese, it would’ve translated as "The Story of Woman Who Decided to be a Prostitute," but we decided to use it as a way to bring "puta" onto the cover. This was Esther’s suggestion. We butted heads, there were some difficult conversations. Tears, definitely. This was Esther’s suggestion, a compromise. We maintained the provocation of the title but brought in this gesture to her regional origins and the kind of broader movement in Sao Paulo.

Laura Murray: Esther and I were the puta defenders. We live in bubbles. With any activism, you get into your world, and I’m very much in the prostitute rights activist world, and everyone knows what puta is, even though I’m from Kansas. I know that’s not true, but I blocked that out somehow. So we were defending this, but when we were in Florida, a colleague of Meg’s saw the cover and said, “Oh my god, I see this word, and I just cringe. Whore.” I immediately looked at Meg and said, “You were right. You win.” It is a powerful word in English, so I think it was a great solution. Thank God Esther had the brilliance and that we continued the project. It was a fantastic collaboration. There was a lot of mutual learning. Between us, we come from three different disciplines and three different ways of engaging with Gabriela and her issues. It was very rich in that way.

Esther Teixeira: I talked to my friend who is doing the translation from Portuguese to Spanish about the problem, and he said, "I agree with Meg that ‘whore” should be in the title." So thank you, Meg, for insisting.

Question: You translated this book with the goal of advocating for sex worker rights. What progress has been made, and where does Gabriela fit into that?

Esther Teixeira: Laura’s documentary is a good testament to Gabriela because, before this translation, it was the only material available in English about Gabriela. There has always been an interest because Gabriela has an interesting trajectory where she was a college student and decided to abandon her studies and go into prostitution. She tells all about that in her book. She approached the profession of a prostitute as a philosopher and thinker. She has much to contribute to the epistemology - the knowledge - of global feminism. From that perspective, it’s worth getting this to as many people as possible, especially considering the global south decentralizing knowledge production. In this case, it has a double effect because it’s not only from a geopolitical place - knowledge production in Latin America - but also topic-wise. It’s a double subversion because she’s not an academic from Latin America trying to break the glass ceiling of Eurocentrism.

There are many ways you could advocate for translating this work. She’s considered one of the co-founders of the sex workers movement in Latin America, and she’s recognized for that by Hispanic activists in Spanish America. We know there are people out there who want to read her. We would like to have the chance to translate it into as many languages as possible, just as if she were a French academic. We want to advocate for that.

Question: Every culture’s interpretation of the work and how they feel about it will generate a different energy wherever you go in the world, and we will really support the movement as a whole.

Meg Weeks: That comment makes me think about my question for Bella. I’m curious because, in Brazil, prostitution is not illegal. Third parties who benefit from the sale of sex are criminalized, but selling and buying sex is not illegal, unlike in the United States, where it’s criminalized in almost the whole country. I’m curious what Bella thinks about now that the work of this activist is available in English and what impact that might have on activism in the United States.

Bella Robinson: It will help shift social perception about the rights of sex workers, and when you have more than half the public standing up for something, that’s when they have to stop. This is a dangerous time. Regardless of what you think about sex work, you don’t have to like it, but we’re being attacked and harmed. When serial killers go after us, the police call us NHI for ‘no human involved.’ They don’t investigate our murders. On December 17th, we hold the memorial online for the International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers. COYOTE has been hosting it for about five years now, and we mourn our people just like trans remembrance day. When we surveyed 1500 sex workers, only 37% were heterosexual. A lot of organizations for LGBTQ+ people are not advocating for their people.

Gregory Mitchell: I was doing work around the Evangelical Christian groups that take a rescue approach and want to funnel everything into the framework of human trafficking. One of my many frustrations was what you’re talking about, Bella, because we know there are so many LGBTQ+ youth who are engaged in sex work, survival sex, and various forms of sexual economy. But the Evangelical groups didn’t want to deal with them. They didn’t want to work with them. Many of them had been cast out by their own families. This is a clarion call that you’re giving to recognize those roots and that solidarity. That’s something that was lost because of FOSTA/SESTA. Kamala Harris was a great proponent, defender, and implementer of FOSTA/SESTA.

Bella Robinson: FOSTA was the “Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act,” and SESTA was the “Stop Online Sex Trafficking Act.” When the internet came up, 85% of sex workers came inside. BackPage became the Walmart of escorts. You could screen clients, and you were safer when working together. All these things are common sense. FOSTA said that if you had more than five prostitution ads on a platform, you would go to prison forever, just about.

I did a FOSTA survey two weeks after it passed. I knew things would change in time, but I wanted to see the immediate effects. It was devastating. The poorer someone was, the worse it was. If you lived in a hotel and used to pay $10 to post an ad and get a client, you pay your rent that day. A lot of people ended up back on the street, and there was violence.

When these groups save somebody, what they do is they dump them in a public shelter and tell them to be good. A lot of it ties into domestic violence because when someone can’t say, “I’m going to call the cops,” and they tell you they’re going evict you and take your children away. It’s a punishment for women who do not conform to what they think.

Laura Murray: I want to read from Carol Leigh’s perspective, which relates to Bella’s statement. Carol was an avid filmmaker and filmed a lot with Gabriela. She says, “In one interview, I asked her Gabriela about the red-herring accusation that prostitution could never be a choice - an assertion as reductive and classist then as it is today. Does one choose to work at McDonald’s? This line of thinking drove me crazy. Gabriela explained that there is some choice, even when choices are limited. “It’s dangerous to start from a position that people have no choices in life,” she explained. “Because if we do that, we can only look at them as victims and victims have no choice and no voice.”

Question: Could you talk a little more about the reception of the original text when it was published in Brazil and what effects it had or what responses it garnered?

Laura Murray: I was not in Brazil when the book was launched. I was there before and shortly after. But I know the cover was an issue because even in Portuguese, a lot of editors did not want it to have the word "puta" on the cover. This is something we haven’t mentioned before. It was turned into a play, and when it was performed, the news and some smaller towns wouldn’t spell out the word. They would just put P***.

The book received a positive reception and sold out. It’s very difficult to get a copy in Portuguese. It was published by a very large publisher, a publisher with a lot of reach in Brazil. It was published three years after Gabriela founded Daspu. I think Daspu had a lot to do, even with why she was invited to write the memoir. The book had a positive reception and has had an effect on sex worker activism.

In 2008 and during the Pandemic, the organization that she founded, Coletivo Puta Davida, got an Instagram message from a sex worker that had read the book during the Pandemic. She had worked for 10 years, had a bad experience, and blocked it out. After reading Gabriela’s book, she decided she wanted to return to activism. There are a lot of stories about sex workers reading the book and rethinking activism. It did have a positive effect. There is also a movie script based on the book that hasn’t been funded yet.

Gregory Mitchell: We haven’t explained Daspu, which will bring us back to translation again because wordplay was so central to Gabriela’s form of activism. She could sit equally with the minister of public health, politicians, and congress members in the favelas doing frontline work. She could function in these multiple registers of delightfully filthy wordplay sometimes and talk policy speak, much as Bella has. Could you maybe explain Daspu?

Laura Murray: The name is a play on words from a store in Brazil called Daslu, which meant “of Luciano. " Daslu was luxurious and one of the most expensive stores in Sao Paulo, Brazil. You could only get there by helicopter or car—there was no way to walk in off the street, which reduced the number of people who could go in. Brazil is an extremely unequal country, and Daslu was the symbol of this kind of extreme inequality.

Daspu was playing on this idea, and at the time, Daslu was under criminal investigation for tax evasion. Flavio Lenz, who founded DaVida and Daspu with Gabriela, wrote a book about Daspu and talked about how they were in a bar - a lot of DaVita’s meetings happened in the bar setting - and they think a journalist overheard them talking about Daspu because there was a little note in a large newspaper talking about the founding of Daspu. Daslu threatened to sue them when they got this note, which was the best thing that ever happened to them because everyone hated Daslu. You had a lot of famous movie stars and television stars coming out and defending Daspu - which was very recent and hardly had anything to sell. They were like, “Oh shit. Now, what are we going to do? All these famous people want to come and buy things and model them.”

Gregory Mitchell: That’s how they got into Brazil Vogue, right? The photo shoots. You had all of these "putas" with these creative fashions. They had a hand in designing the fashion. The T-shirts were the easy big sellers, but there were also these collections. Did you talk about the bride?

Laura Murray: This is in the book. I helped a lot with the photos in the book. If it were up to me, there’d be 200 images in this book, but they capped us at 20. There’s a photo of the wedding dress. It’s white and made out of used sex motel sheets, and the train is made from pillowcases from sex motels throughout Rio. The tiara is made of condoms. Not used.

It is a work of art. It was made by an artist, Tadej Pogačar, who made it for the 27th Sao Paulo Biennial exhibit in 2006. Right now it’s in Berlin, it’s circulating. The first Daspu collection all had to do with prostitution. The first one was an ode to sex workers who worked with truckers. It had a trucker theme - many things had tire prints on them. There was another that joked about food because in Brazil, the word to say "to eat" is also "to have sex." There was a whole collection asking, "Did you eat today?" It was always very playful but very provocative.

Question: Is the book written more for an academic or popular audience?

Meg Weeks: I hope it appeals to a broad audience. We’re all academics, and we wrote the introduction to some extent with an academic audience in mind. Still, we wanted to give context to those who weren’t familiar with but perhaps interested in sex work activism but weren’t familiar with Brazil. There are a lot of annotations and footnotes, but as the translator, I hope that the text stands on its own as a literary text because it is beautiful. It’s in plain speech, and I wish I did that justice in my translation and captured the kind of humor and reverence of her prose.

Esther Teixeira: The chapters are structured as a play on the Ten Commandments. Every chapter is one commandment directed to prostitutes. For example, the first command, the Whore’s First Commandment. "You shall be discreet; you shall never point to a man in the street and say he’s the client." The chapter develops on that. Gabriela always said you don’t talk about what happens in the bedroom. In her book, she takes a different approach. That’s why we want to do a community launch as well as an academic launch. Everywhere we went, we did a book launch at a local bookstore and an academic talk because we believed the book had enough bandwidth for all that.

Question: You said she wrote two memoirs, and I was just curious about the different scopes and how you were able to choose this one over the other.

Esther Teixeira: I love the first book. She published it in 1992. She explored the relationship between the beginnings of the movement and the Catholic Church in Brazil through liberation theology. In the first book, she explores what it meant to her to have found for the first time a group of intellectuals who were approaching the prostitutes to offer help and to dialogue. Then we grow with her as we read because she says she was at first so touched by hearing people saying prostitutes are oppressed. And then suddenly she realized that wait, they’re saying, “I am oppressed, and I have no control over what happens to me.”

She said that at certain points, she became a nun to liberate the Catholic group she was working with. The book we translated is a more mature Gabriela. She passed away in 2013, and this was published in 2008. There’s a lot of value in reading the second one, at least to start. Meg is probably going to translate the first one as well. We’ll be back here.

Meg Weeks: As a scholar, I find it interesting to grapple with using memoirs, oral histories, and testimonial literature as a source space. In 2008, Gabriela was a household name. She had a legacy to shepherd. It’s interesting to see how specific episodes of her life are remembered differently in her second memoir, probably to tend to her legacy and attend to her reputation as a social movement leader.

Esther Teixeira: Bella, you are a staple of the sex work movement here in Rhode Island and nationwide, I would say. Is there something that you would like to end on?

Bella Robinson: My mentor taught me I must attend universities and college students because they will be the next generation of voters and policymakers. Sex work is work. The government and police are our bosses. We must go to them to negotiate our safety and address the stigma. This is going to be a generational fight. Even before Trump, this wouldn’t have been done in my lifetime. We’re doing it for the next generation.

This piece, on Brazilian sex worker rights activist Gabriela Leite’s book Daughter, Mother, Grandmother, and Whore has been translated into Portuguese by Renato Martins

If you read Portuguese, find it here:

Livro de Gabriela Leite ganha edição em inglês

https://mundoinvisivel.org/livro-de-gabriela-leite-ganha-edicao-em-ingles/

It was great to see you Steve, Thank You for coming out to support us. You really out did yourself on this article .

Esther my friend it was so good to see you again. It was an honor to meet Laura and Meg in person.

Monday evening we did a reading at Pembroke. Thank you Elena Shih for bringing me the letters you students wrote to me. When I am done treasuring them they will become part of COYOTEs Archive at Brown.

Several people asked about Coyoye new book “Sex Work Policy: Participatory Action Research By and For Sex Workers and Sex Trafficking Survivors”

Sex Work Policy marks the coming together of cutting-edge participatory action research by and for people in the sex industry, illustrating how policy shapes their health, safety, and working conditions. While much has been written about people in the sex industry and how laws and policies affect them, we rarely hear from them. This is the first book compiling the experiences and voices of thousands of people in the United States' sex industry.

About the research:

People in Alaska’s Sex Trade - Their Lived Experiences and Policy Recommendations was research conducted by Tara Burns in Alaska, who is the author of Chapter 1

The other five surveys were conducted by COYOTE RI under the leadership of Bella Robinson, founder and executive director of COYOTE RI. The data was then achieved at Brown University Pembroke Center for Teaching and Research on Women- Coyote RI Survey Collection

We are grateful to Alex Andrews, SWOP Behind Bars, and Cris Sardina Desiree Alliance, who helped workshop the 145 questions in the 2017 US survey. Bella spent countless years getting US sex workers to participate in five COYOTE RIs surveys.

In 2020, COYOTE RI and volunteers had already drafted ten chapters, at which time COYOTE RI hired Tara Burns as their research and policy director (2020-2024). Over the next three years, Tara Burns, with the assistance of several COYOTE RIs interns and volunteers, helped edit and reformat the book. We are grateful to Tara Burns for her contribution, for compiling 10 years of COYOTE RIs research into " Sex Work Policy"

Available on Amazon

https://tinyurl.com/bdev55aa