As a developer plans to place 58 student housing units in a historically Black neighborhood, residents react

Why are these areas targeted for such development? The answer is complicated, but includes historic racism and opportunistic developers.

Two people who did not attend Monday's community forum regarding a proposed 58-unit micro-apartment complex aimed at the East Side were Madonna and Butch Trottier. But in their absence, around 200 East Side residents attended to express their dismay at a plan that would increase housing density in the neighborhood near the corner of Evergreen Avenue and Camp Street, but at a cost to the neighborhood that all in attendance seemed unwilling to pay.

The meeting was called by Providence City Councilmember Susan Anderbois (Ward 3) to address resident concerns. Councilmember Anderbois shared that she had received over 100 emails opposing the project.

You can watch the video of the forum here:

Historic underinvestment and gentrification

“I want to note before we get started, the unique nature of this neighborhood,” said Councilmember Anderbois, noting the historical forces of systemized racism that permeate this section of the East Side. “Camp Street and Lipppitt Hill have historically been subject to discrimination and active disinvestment by the city. If you haven't read the city's A Matter of Truth report, I highly recommend it. I want to note that many Black residents were forcibly removed from Lippitt Hill to create what is now the Whole Foods shopping center in the 1960s and 1950s. I want to be mindful of this neighborhood and how we are treating this neighborhood.”

State Senator Tiara Mack (Democrat, District 6, Providence) added that this kind of development seems targeted at lower-income Black and brown communities.

“I represent District 6, which is a constitutionally protected Black majority district in Rhode Island,” said Senator Mack. “That is historically significant because projects like this are being proposed throughout Senate District 6, not just in the historically Black Mount Hope neighborhood, but also in Upper and lower South Providence, where the burden of addressing our housing crisis has disproportionately landed on Black and brown communities that have already seen historic displacement.

“I am a huge supporter of density in our communities and our state. I went so as far as introducing an end to single-family zoning or inclusionary zoning across our entire state because I believe that to address our housing crisis, we need to be able to build more densely. [But] we have to be responsive to the communities that already exist and we cannot place the burden on low-income, historically and currently Black and brown neighborhoods. That leads to their ultimate displacement out of our cities and out of our state.

“What does that look like? That looks like making sure that when we are planning our cities and increasing density, we see what communities are already bearing that burden and what communities are not holding their fair share of the responsibility for building more density.

“This neighborhood is already zoned for [this kind of density while] right up the street, we have a neighborhood that has exclusionary zoning [R1 zoning]. R1 zoning allows single-family homes only, which means that on a single plot of land, there can only ever be a single-family home, which means they will never have density and that they are not going to experience some of the conversations that we're having here today...

“You might not know the history of Lippitt Hill. You might not know the history of Olney Street being a historically Black neighborhood that saw displacement, or why District 6 is so funkily shaped and is cut through by a highway - which was created to intentionally displace Black and brown communities, which no longer exist, or about historic Downtown Providence, which was the site of the slave trade in our city.

“There's a lot of rich history in this neighborhood. I hope that you all will take some time to hear about that, but also listen to the real and valid concerns of folks who have been in this community for decades and are seeing their communities as a place that is not respected, prioritized, or being considered when we're thinking about planning. When we're thinking about our cities and thinking about who deserves to be in Providence, who deserves to stay in Providence, and what we consider building cities that work for every single person with a racial justice lens.”

Harlan Perry, who owns property on Camp Street, added to this history.

“I was born and raised on 100 Evergreen Street, and Mrs. and Mr. Jake were pillars of the community. We used to go to Mrs. Jakes to buy penny candy,” said Perry. “If you know Mrs. Jake, you couldn't ring the bell more than twice or she would tell you, ‘Boy, I know your mama, so don't have me come over there and talk to her about it.’

“When we're talking about the displacement of Black people in the community - when I grew up there, you knew everybody. It was family after family after family. And the way we grew up - I tell my kids all the time - it was so special riding down Blackstone Boulevard with our bikes going to the bike trail, just so many different things that that community bought to us.

“I played football for Hope High School. I graduated in 1985 from the school. We walked to Third Street every single day, to see buildings and houses being torn down and these big buildings being built. I could be wrong, but what has Brown University done for Hope? Nothing.

“When we sit here and we talk about displacement and the lack of housing, let's look at the whole picture. The residents should have a huge say in city planning. Not just the people who are on the council or anything like that. It should be residents first because we pay the taxes that are going up every single year, and that's part of the reason why people are being displaced in the community.”

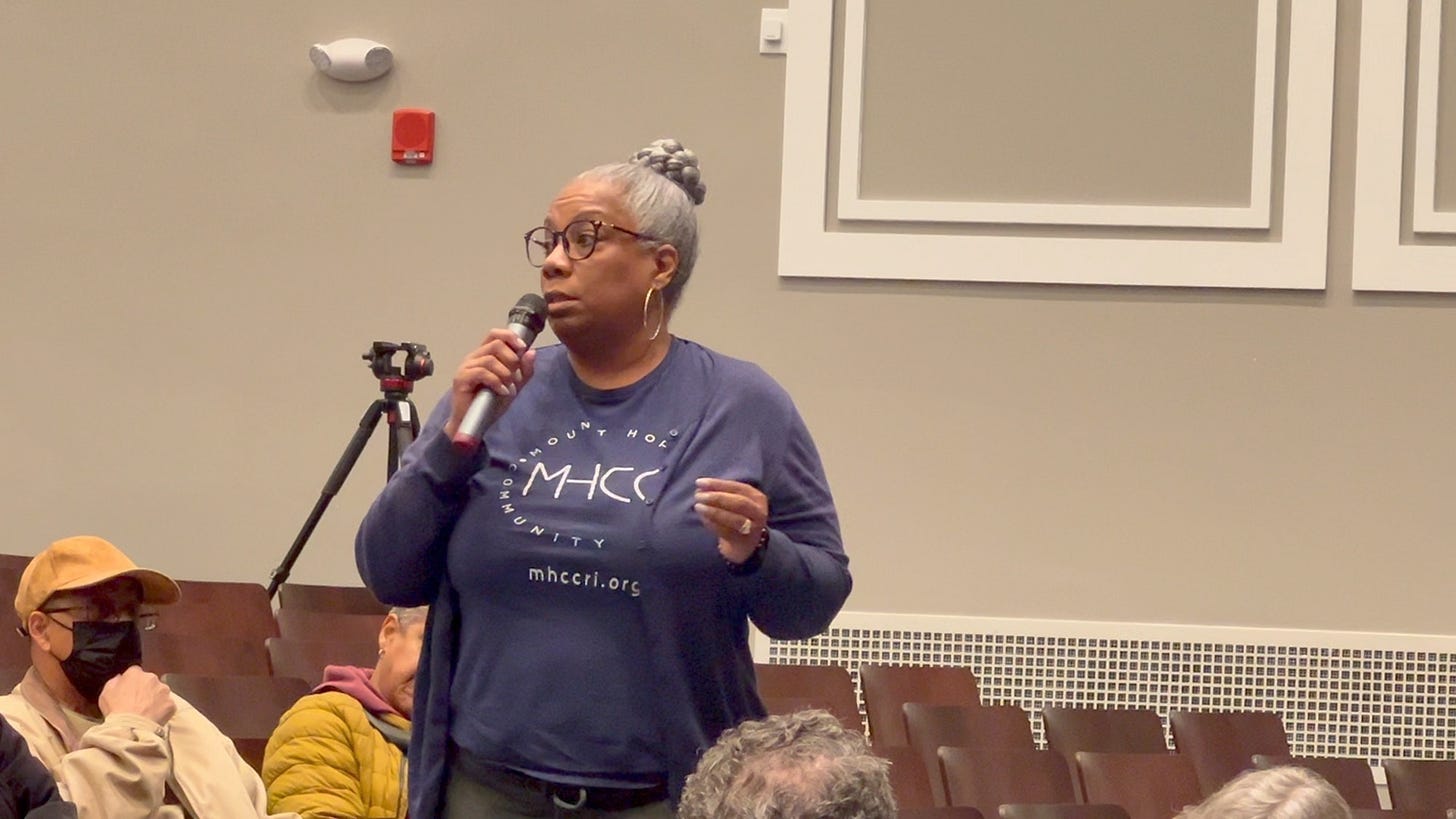

“I am the executive director of the Mount Hope Community Center,” said Helen Baskervilles Dukes. “I also live on Camp Street directly across the street from the park... I was born on Grandview Street in that brown ugly house. I can give you a bit of history about the East Side and for those who've lived here a long time...

“Like Sue said, it's government disinvestment... Sometimes, when you look at the Black community, people think that we don't want better for ourselves, but we know historically [that] we don't get the resources things that other communities get.

“We own the turnaround directly across the street from this property and we are looking forward to building affordable mixed-use housing there. We're going through the process and we're going to have a community forum because we want to hear what the residents have to say... Bear with us. We're trying to make sure we're providing affordable and nice housing for families that have been historically displaced.”

The Project

When developer Dustin Dezube acquired the East Side property, he initially proposed building five rental townhouses on the property. After that plan was rejected, he proposed cramming 58 units in the same space.

The future of the project depends on the Providence City Council, which can vote to change the zoning to allow such a development.

The Developer

At 79 years old and facing homelessness, Madonna Trottier chose to sleep in her car with her son Stephen rather than apply for elderly housing without him. Two years before her death, after facing eviction and homelessness, her husband Butch had died.

In 2018, before her eviction, Madonna showed me around the first-floor apartment on 40 Grove Street where she and her family were being evicted. On a fixed income, Madonna told me that she once had to throw away all her groceries because mice chewed through the boxes.

I wrote then:

“A window in the empty third-floor apartment at 40 Grove Street in Providence had blown open in the night, letting out heat and letting in an early morning, below-freezing draft. Other windows in the first-, second-, and third-floor apartments are nailed in place or tied shut with bits of string or stuffed with garbage bags and newspaper. Thin, gauzy tape covered the seams that separated windows from walls in some rooms. You could look outside the apartment through the space between the ill-fitting front door and door frame. The ceilings leak and mice sometimes come up through holes in the baseboard of the closet.”

At Monday night's forum, the man who evicted the Trottiers into hospitalization, homelessness, and death stood up to speak in defense of his project on the East Side. For simplicity, I've identified all the questions he took questions from as the “Audience.”

Dustin Dezube: Thank you for coming out on a Monday night. I've been to meetings like this before. I'm very impressed with the community here. There were a lot of good questions raised and what we did was we took notes on them, we wrote them down, and I look forward to continuing the dialogue with Councilor Anderbois ... and the community. There were good points raised and we'll take that into account.

Audience: Why were the five planned townhouses rejected?

Dustin Dezube: It came down to how the dimensional requirements are calculated. It was the front setback, which is calculated based on neighboring properties. And it was determined that the townhouses we were proposing because they had garages on the ground level, were too close to the street and needed to be set further back. We did not have the dimensional relief to build the townhouses.

Audience: Why 58 units from 5?

Dustin Dezube: As Councilor Anderbois noted, it is very early in the process for us. We do things in an iterative fashion. We listen to the feedback that we get, and we respond to the feedback that we get. Even before tonight, we heard a lot of feedback from you that 58 was too much. That's no longer on the table. We've already committed to lowering the unit count to 45, which I know is more, I know that it's more than we want to see...

Audience: [LAUGHTER]

Dustin Dezube: I am listening... There's a lot of complexities to these decisions. Many things come into this, and everyone's concern here is part of that.

Audience: Do you live on the East Side?

Dustin Dezube: No. I used to live in Providence and I used to live in multiple parts of Providence.

Audience: [Quietly] He lives in Wellesley.

Do you live in My Neighborhood?

Dustin Dezube: I do not.

Audience: Where do you live?

Dustin Dezube: Out of state right now. I do work in Providence every single day.

Audience: You don't live here. Would you build this next to your home?

Dustin Dezube: I think that's a really good question.

Audience: No, you wouldn't.

Dustin Dezube: To be honest, there was a proposal, right next to a place where I am building a home where I will be living and it was much larger than I would ever have anticipated. And the person in the building reached out to me and asked for my support as a neighbor. I can tell you that I thought long and hard about it and ultimately I decided to support the project.

Audience: Do you have pending litigation against you for your other properties? You got to bring a lawyer with you and I get it, you got to protect yourself. My thing is that this family-owned that [property and] you probably got [that property for a] freaking song and you got to make this huge building to get all this money in. Do you know why he's not building on North Main Street? It's going to cost him a shit load more to buy that property when he can steal it from somebody else. We don't need that here man. And if the litigation is true - your attorney may only work with you on this project and that project - but what about all your 60-some-odd properties? Do you have pending litigation against you because of quality?

Answering the question about Dezube's alleged violations and litigation, Dylan Conley, Dezube's land use and development attorney said, “In terms of discussion about other violations, I'm not aware of other violations that are relative to this application or other projects more generally. I do a lot of work with this developer and you basically cannot get a permit. If you have outstanding violations.”

Kevin Diamond, Dezube's architect: I would love to shift the dialogue and I want to propose something a little bit different. I think that this is very early in the design discussion. I can assure you that nothing that we're doing is a negotiating tactic.

I know that it's easy to think and say those things. I promise you that where we're early in the design process - very early - I think that a really intelligent next step would be to do what we would call a design charette session. What would be helpful is that anybody who would want to attend, we can maybe speak with Councilor Anderbois about this, is a meeting where we can sit down and positively exchange ideas.

I would like to understand what you want to see, the specifics of how we can build something nice together, and how we can positively develop this. I don't think that there's a way to make every single person a hundred percent happy, but we'd love to come up with a way to have a meaningful dialogue.

In 2022 a group of Dezube's tenants rallied to demand, “increased responsiveness and timeliness from the company, as well as safe and dignified housing for all residents.”

Organizing as the Providence Living Tenants Union, at least 22 renters experiencing terrible conditions in apartments throughout Providence created a list of demands. Joined by allies, they marched to Dezube's Providence Living offices at 296 Wickendon Street and taped the demands to the door.

Tenants complained about broken appliances, a lack of hot water, mice, and of course, "literal mushrooms growing out of the ceiling. Not mold, but mushrooms…”

Councilmember Anderbois ended her forum by announcing that she would be recommending that the City Council reject Dezube’s request for a zoning change.

thank you for this detailed reporting. We were there for part of the meeting and it’s really helpful to see in text what some of the speakers said.

Well, there doesn’t seem to be any positive community based consideration or respect now or in the past exhibited by Dezube so there is no need to accommodate him on any level.